I dont think anyone would argue that over the past 30-odd years professional football has changed out of all recognition.

Off the field it has become a corporate world of big business, high finance, tycoons and agents.

And even when the players step across that white line it is different.

Character is certainly not a word I would use about todays footballers. They all seem to be clones, the majority quite boring.

I played with people like Stan Bowles and Charlie George real characters. Before my time there was Rodney Marsh and Frank Worthington, players that people would pay good money to turn up and watch. How many are there today? For my money, the last real character was Gazza.

And you could say the same about the referees. We had Clive Thomas, Roger Kirkpatrick refs you could have a bit of banter with, refs who gave as good as they got and who you respected for it.

Its all changed. Money rules everything at the expense of tradition and a real love of the game.

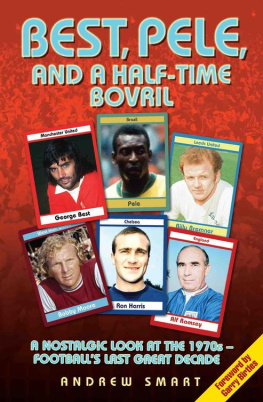

Andy Smart reminds us of the days when football had a real sense of value and fans could easily identify with the teams and players they supported. The great names like Best, Pele and my old team mate, John Robertson. Great games like the day Hereford shocked Newcastle in the FA Cup. And great managers like that pair I played for Clough and Taylor.

For those reasons and those memories, I certainly have no problem with Andys argument that the 1970s was footballs last great decade.

W hen a brittle north-westerly wind is blowing down off the Cheviots, there can be few bleaker outposts of the Football League than Brunton Park, Carlisle.

I remember it well.

A glacial February afternoon in 1979. Down on the pitch in front of a sparse and well-muffled crowd of diehards, Carlisle United were entertaining Mansfield Town in the old Division Two. (I use the word entertaining in its social context, not as a critique of the match.) From my freezing, hard, wooden seat in the press box, I attempted to deliver a coherent report via a faint telephone line to the Football Post in Nottingham. I gazed up at the frosty green hillside in the middle distance, arched behind what is now catchily named the Pioneer Foods Stand, and tried to count the sheep.

It was at romantic venues such as Brunton Park in Carlisle, Edgeley Park in Stockport, Feethams in Darlington and Plainmoor in Torquay where I spent most Saturday afternoons during the late 1970s. At Spotland the once-rickety home of Rochdale I recall a game of near-stultifying tedium. At last, the final minute; Mansfields stout defensive performance had given them the better of things for much of the previous 89. My bellowed dictation reflected this superiority with, perhaps, a little bias for the benefit of our local readership.

With the referee about to bring a blessed end to the stalemate, the Stags stupidly gave away a penalty and I had to report, faithfully and accurately, that the officials decision was wholly justified. Sitting in Spotlands open press box, with spectator seating all around, I felt a light tap on my shoulder. I glanced around to be confronted by the gurning face of a veteran Dale supporter. Eh, lad, he said in a broad Lancashire tone from beneath a grease-stained cap, its peak sharp enough to slice bread. Thats first true word thee ave spoken all tmatch. At that precise moment in my young and stuttering career I wondered if my journalistic heroes, Ian Wooldridge or Hugh McIlvanney, had ever had such a richly invigorating experience on a visit to Old Trafford or the San Siro.

These isolated memories underpin my raison dtre for this book. I missed much of the live action of the 1970s. While Liverpool were winning titles and European Cups while the real football was unfolding at Highbury and at Old Trafford while my own club, Nottingham Forest, was pre-eminent under Brian Clough I was trawling around the backwaters of the Victoria Ground, Hartlepool, and Gay Meadow in Shrewsbury.

I have to confess, I was in my element. I had been hooked on football from Day One, 26 October 1957. I was 10 years old and my father took me to the City Ground to watch Forest play Blackpool. To be honest, I dont remember too much about the match. We stood on the terraces but not together. As was the quaint tradition in those days, I was passed down to the front and did not see my father again until the final whistle blew. If truth be told, he was not a great fan but I was intoxicated by the atmosphere of a 41,000 crowd: a monochrome, flat-capped mass of bodies out of which rose a thick pall of steam and tumultuous roars. The ball was dark brown; it was also thickly stitched. The players boots were laced to just below the knee. The shorts were baggy and flapping.

I recall one incident from that match, which Forest lost 2-1. They had an abrasive, impudent little inside forward named Johnny Quigley. Right in front of me he got the ball and took on the first Blackpool player who came in with a quick challenge. He just happened to be Stanley Matthews Footballer of the Year; Legend; Hero. Quigley nut-megged him. Matthews was not best pleased but the crowd loved it.

Over the next 20 years Forest had their fleeting moments: an FA Cup win in 1959, when FA Cup wins meant something; Division One runners-up in 1967. But no one in their right mind would dare to have predicted that Forest, along with many other sides now viewed as bit-part extras, would play a leading role in footballs last great decade.

Perhaps my album of the 1970s is coloured with self-interest. For me, it was the decade. Not a particularly great period of world history: the first real oil crisis squeezing the pips out of world economies; Britain gripped by industrial turmoil; the three-day week and power cuts; the Troubles in Northern Ireland; tension in the Middle East. The permissive 1960s had passed. The times they were a-changing.

Football was no different. The 1960s had seen the end of the maximum wage, bringing the most profound changes the game would see until the Bosman ruling. As the 1970s dawned the first million-pound transfer fee was still nine years away. But player power was fast approaching. Big business was taking over too; balance sheets were soon to become more important than team sheets.

The 1970s saw the last throes of the working-mans game. It was footballs last democratic decade when clubs from the sticks could dream of a championship, the FA Cup, even European glory. From Everton in 1970 to Liverpool in 1979, six different clubs won the Division One title: Liverpool four times; Derby County two; Everton, Arsenal, Nottingham Forest, Leeds United. The chances of a Derby, Forest or Leeds doing that now are unimaginable. Since 1980, the big four Manchester United, Liverpool, Chelsea and Arsenal have won the title 29 times out of a possible 34.

So we can be forgiven for looking back nostalgically at the 1970s. It was a different time, a different era; a different world. And despite the hysteria whipped up by the media in trying to persuade armchair fans that the Premier League race has never been more exciting, try telling that to fans of Wigan, Norwich, Aston Villa, Everton, Fulham, Sunderland and the rest of the Premiership cannon fodder whose fans cannot begin to dream about challenging for the title because it will never happen.

Football in the 1970s was played on a Saturday afternoon and kicked off at 3pm. Players ran around but never rolled around. The only person you saw wearing multi-coloured boots was Elton John, and gloves were the exclusive possession of goalkeepers.