AMERICAN DEMAGOGUE

AMERICAN

DEMAGOGUE

The Great Awakening and the

Rise and Fall of Populism

J. D. DICKEY

PEGASUS BOOKS

NEW YORK LONDON

Liberty without obedience is confusion, and obedience without liberty is slavery.

William Penn

F or students of history or political science, it seems self-evident: A demagogue is a politician or ruler who incites his audience through appeals to emotion, denigration of his enemies, blatant lies and insults, and impossible promises of a greater world to come. He may also call for a return to a mythical past, in which strength and tradition held sway before the modern world ruined everything with corruption and weakness. A demagogue can be merely a public agitator and gadfly, or he can evolve into a murderous dictator, depending on how much power he can accrue through public opinion, mass propaganda, government bureaucracy, and armed force.

Though there are exceptions, demagogues are almost always men. They may rise to notoriety through elected office, corporations, the media, the military, or simply appear out of nowheremagnetic personalities blessed with the gift of oratory that attract a mass of followers and build a cult of personality. Our Western understanding of them goes back to ancient Greece and Rome and continues with todays politicians. Such firebrands represent all that is combustible and dangerous in public life, and demagoguery is said to be like an electric shock to the body politic.

Defining who is a demagogue can be a challenge, as the term has been used as an attack word for hundreds of years. In the context of Western democracies, its meaning is fluid and subject to interpretation. For one persons menace to society may be anothers tribune of the people; and scabrous rhetoric to the ears of an enemy may sound like common-sense wisdom to an ally. The judgment about who is and isnt demagogic is based as much on human emotion and tribal loyalties as it is on partisan politics. The reaction of the heart to such a public figurewhether it be praise or revulsionmatters more than the rational judgment of the brain.

At present, Donald Trump has the reputation of being the architect of contemporary demagoguery. And indeed, he shows many of the characteristics: the emotional harangues delivered to mass audiences, the attacks on minorities like Hispanic immigrants, talk of conspiracies like the deep state bureaucracy, the barrage of fake news (either denounced or defended), juvenile insults against his foes, and the slogan Make America Great Again emblazoned on a wide range of affordably priced merchandise. He heralds a return to the halcyon days of the mid-20th century, or perhaps the mid-19th century, and condemns the various opposition politicians, reporters, judges, veterans, statesmen, world leaders, and common citizens who have questioned or criticized him. Indeed, to his opponents, Trump is such an ideal example of a demagogue that it stands as a wonder he does not read or study history, since so much of what makes him typical of demagoguery has appeared again and again in the annals of American life. Huey Long, Father Coughlin, Joseph McCarthy, the Know-Nothings, the Dixiecrats... the list goes on.

That said, demagoguery is not confined to a single person or political party. Although few leaders exhibit as many characteristics of the incendiary style as Trump, there are a number of individuals on the political left and right who inflame public opinion in pursuit of money and votes. Some of them warn against a sinister cabal of billionaires who would rob common people of their dignity and delight in their misery, all to make a quick buck. Others claim to speak for average Americans, whoever they might be, and imagine themselves as their champion against the wicked designs of those who would oppress themi.e., members of the other party. Still others go for the rhetorical throat and employ weasel words to defame one minority group or another, using terms like welfare queens or international bankers or immoral deviants to summon outrage and inspire their audience to offer more campaign donations, often at the same time. The variety of hateful, instigating language in public life is almost endless, though the reaction to it is often the same: offense from those attacked, followed by a hardening of tribal loyalties and a greater schism between factions.

Demagogues were present in American public life even before there was an Americaand the notion that a figure like Trump could only emerge from our technology-saturated, hyperconnected world is false. A contemporary demagogue might use that hyperconnectivity to better spread his message to his followers, but such figures have always seemed to possess a unique insight into how to use technology to their benefit, regardless of how advanced that technology may have been. What an angry tweet is to the 21st century, an angry pamphlet was to the 18th: a method of mass communication that enabled the demagogue to target his audience in the quickest and most effective fashion.

For hundreds of years, the demagogues methods have been consistent. He uses fear and terror to agitate his followers, denounces his enemies with stirring and dramatic rhetoric, and finds new and groundbreaking ways to build his reputation and power. He glories in controversy and never backs down from a fight. He inspires passion, breeds division, turns friends into enemies, and leaves society reeling. He is bold and clever and adroit, and can spread turmoil with ease, but can never seem to master the forces he unleashes. For while the demagogue plays a key role in any social upheaval, sparking it and feeding its flames, he is often consumed by it when the fires became too hot to be contained.

Which brings us to the Great Awakening.

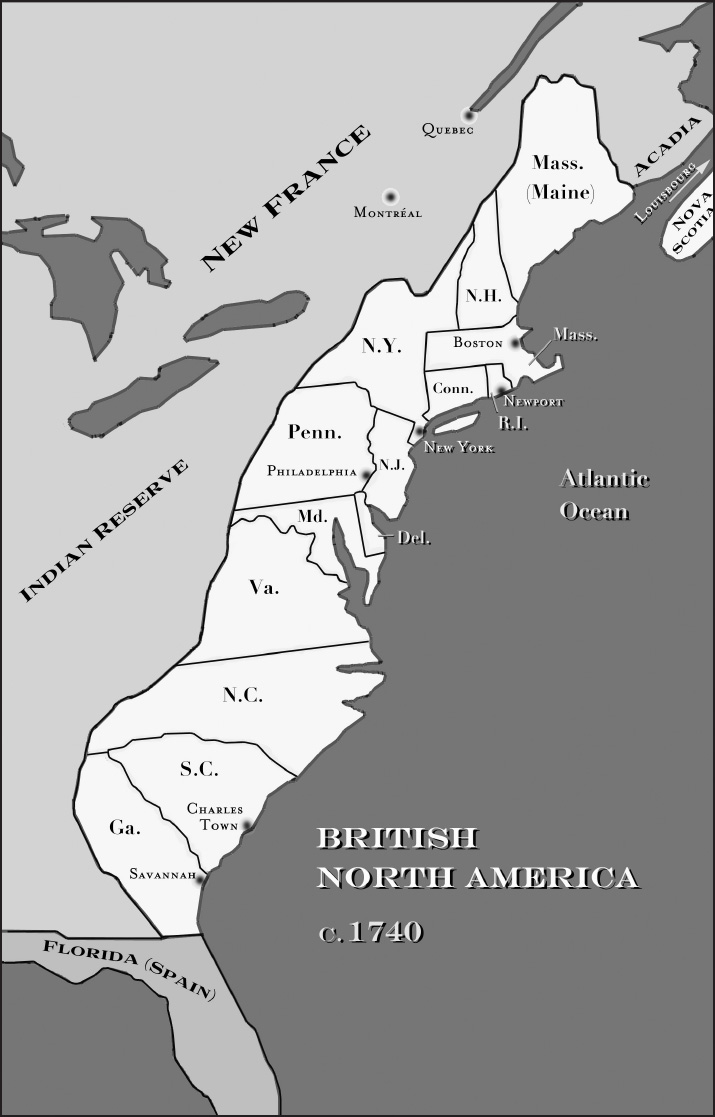

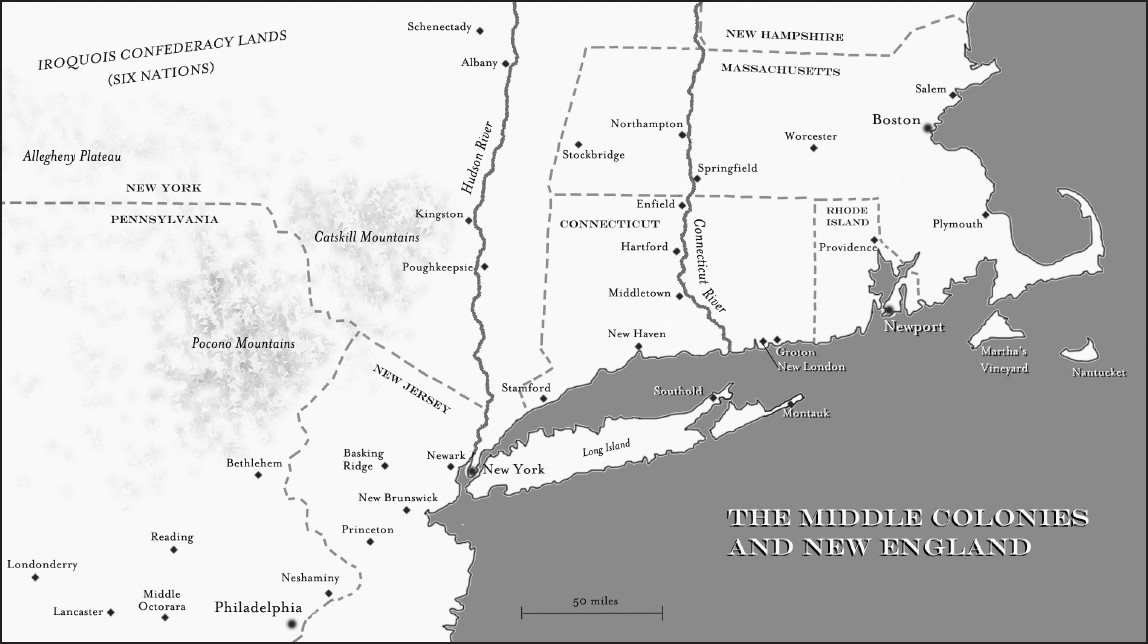

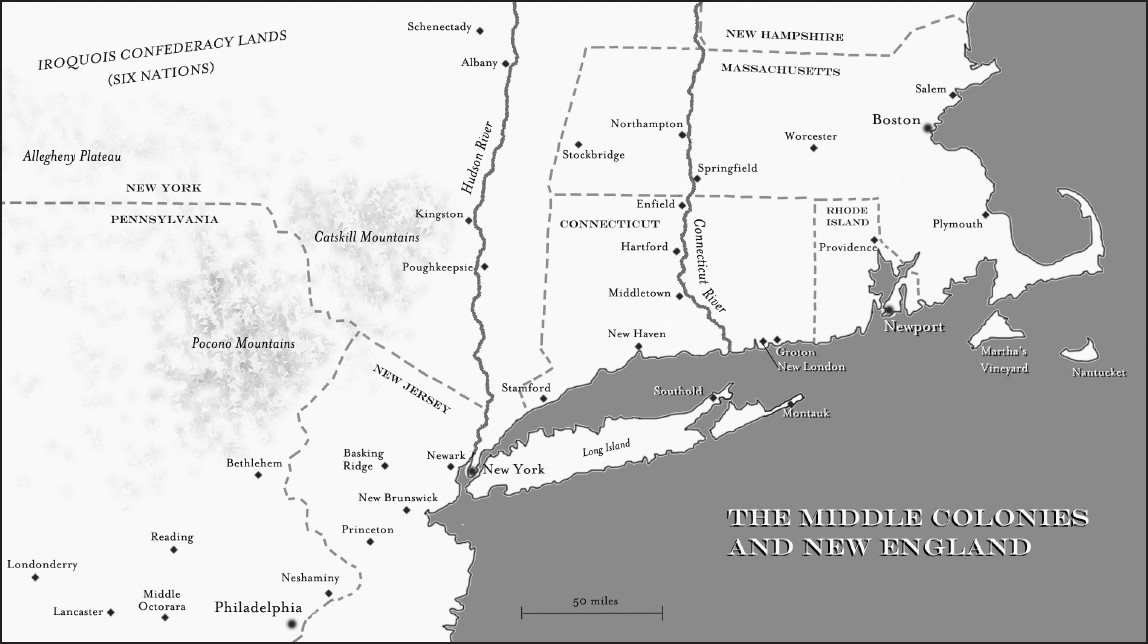

Firebrand ministers were essential to the growth and spread of this religious movement. They built their reputation through mass communications and exhausting travels over hundreds of miles, proclaiming the beauty of the New Birth in Jesus Christ and denigrating those who resisted it. Using powerful rhetoric, they compared their foes to agents of Satan and the Antichrist, yet they also inspired such devotion in their followers that their preaching tours had a joyful, carnivalesque quality. They outraged their enemies, and divided Christian denominations into hostile factions. They lionized the antique Puritan past and criticized the failings of 18th-century contemporary life, but also promised a bold new future of piety and transcendence. Above all else, they were fundamentally American and set a precedent for the kind of political religion, or religious politics, that is still with us in the 21st century.

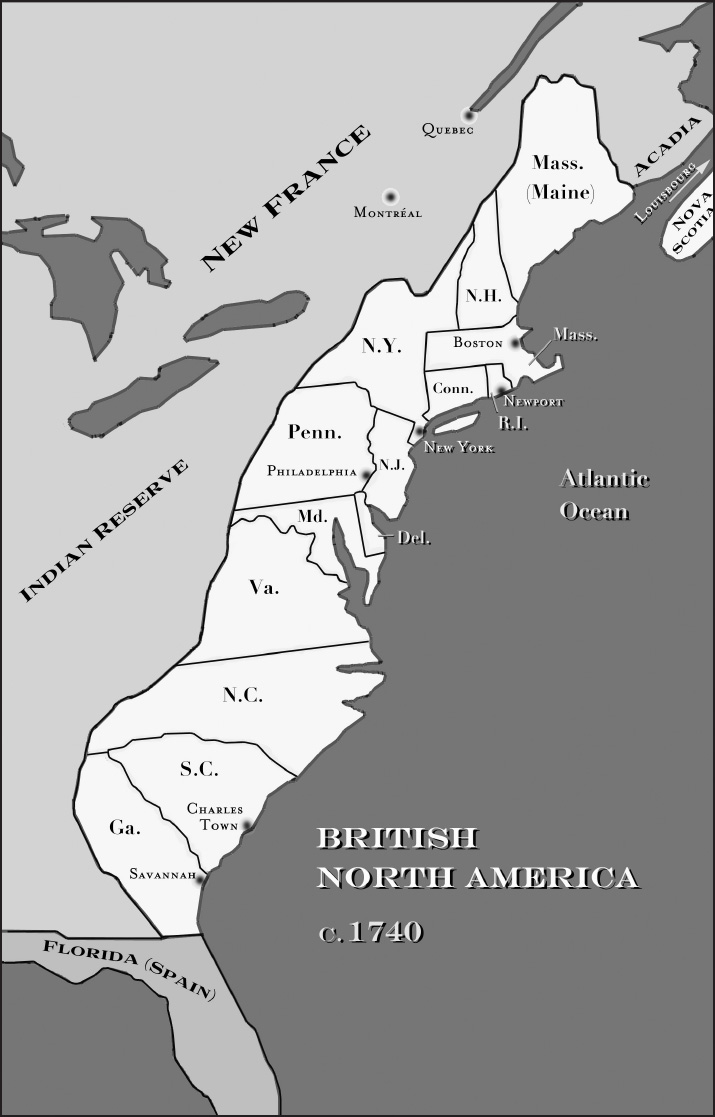

Surprisingly, their story is little known today. Indeed, discussions of the movement rarely take place outside of religious studies, colonial American history, and evangelical Christianity. When the revival does appear in textbooks, it is often mentioned solely as a forerunner to the more familiar Second Great Awakening of the 19th century, or as an example of the kind of late-period Puritanism that reveled in hellfire and brimstone. But to those who study this period, the truth is much richer. The Great Awakening was a transformative event that opened a chasm between the stodgy traditions of the colonial world of the early 18th century, and the trailblazing, tumultuous nation of the Revolution. It represented a boundary change in how Americans thought of themselves, or even that they thought of themselves as American at all, instead of simply being British.

Next page