FINDING

HOME

FINDING

HOME

REAL STORIES OF MIGRANT BRITAIN

EMILY DUGAN

Published in the UK in 2015 by

Icon Books Ltd, Omnibus Business Centre,

3941 North Road, London N7 9DP

email:

www.iconbooks.com

Sold in the UK, Europe and Asia

by Faber & Faber Ltd, Bloomsbury House,

7477 Great Russell Street,

London WC1B 3DA or their agents

Distributed in the UK, Europe and Asia

by TBS Ltd, TBS Distribution Centre, Colchester Road,

Frating Green, Colchester CO7 7DW

Distributed in Australia and New Zealand

by Allen & Unwin Pty Ltd, PO Box 8500,

83 Alexander Street, Crows Nest, NSW 2065

Distributed in South Africa by

Jonathan Ball, Office B4, The District,

41 Sir Lowry Road, Woodstock 7925

Distributed in India by Penguin Books India,

7th Floor, Infinity Tower C, DLF Cyber City,

Gurgaon 122002, Haryana

ISBN: 978-184831-864-9

Text copyright 2015 Emily Dugan

The author has asserted her moral rights.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, or by any

means, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Typeset in Garamond 3 by Marie Doherty

Printed and bound in the UK

by Clays Ltd, St Ives plc

About the author

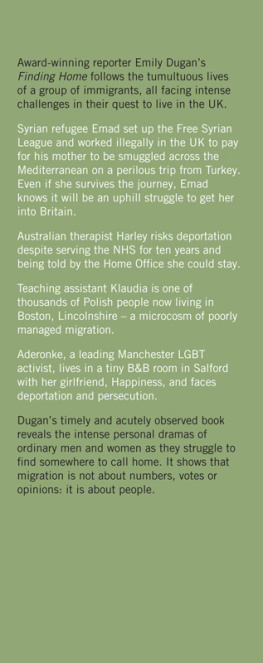

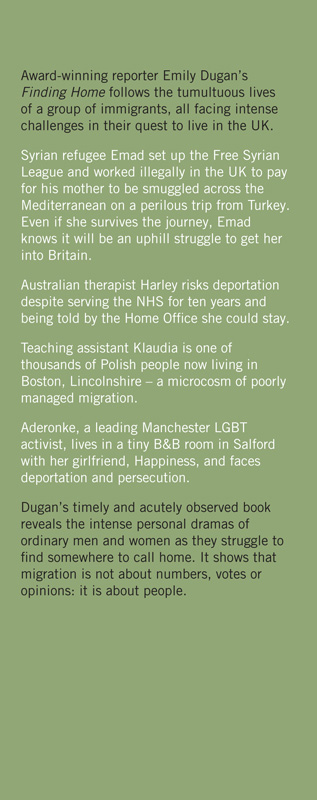

EMILY DUGAN is Social Affairs Editor at The Independent, i and The Independent on Sunday. Her investigations into human trafficking have twice been awarded Best Investigative Article at the Anti-Slavery Day Media Awards and her human rights journalism was shortlisted for the Gaby Rado Memorial Prize at the 2012 Amnesty Media Awards. This is her first book.

For Oly

Prologue

I t was an unusual way to start the New Year: a dawn flight to Romania followed by 52 hours on a bus back to London. I wanted to catch the first coach leaving Bucharest in 2014 and witness the journeys made by people coming to Britain amid hysterical headlines predicting floods of new migrants. The glimpse it offered into the experiences of those making a life in the UK is what prompted this book, which explores the unseen lives of ten migrants from around the world.

As the public debate about immigration gets noisier, it is too easy to forget that we are talking about a collection of individuals. In this hyped-up discourse, newcomers are often talked about in terms of numbers or worse using the metaphors of pestilence and invasion. Even those defending migration often do so with unhelpful generalisations or an over-reliance on cold statistics. Their arguments fail to calm a debate that has always been more about gut feeling and identity than economics.

Generalisations have sullied the debate on all sides. How can a huge variety of people arriving from across the planet all be faceless scroungers? Or, as some liberals might have it, a homogeneous mass of saints who are all better and harder-working than us?

Over the last year I have immersed myself in the experiences of ten people who have arrived on this island over the last decade and attempted to make it their home. I travelled across Europe with Syrians trying to sneak into Britain; went to a mosque in Newcastle with Pakistani men who would be killed for praying back home; attended a Polish-language Mass in Lincolnshire so popular that much of its congregation watch from the car park; trudged around Glasgows homeless services with a man left stateless and homeless by a squabble between Zimbabwe and Britain; and witnessed a judge deciding in a court on an industrial estate whether one of the countrys leading NHS therapists should be banished to Australia.

It was a privilege to spend time with them and be let into their homes, cars and secrets. But in the scheme of their lives I was there only for a relatively short time. For this reason, with the exception of the prologue and epilogue, I have edited myself out. My experiences as an onlooker do not merit making me a part of their history.

This is not supposed to be a definitive picture of every immigrant experience in Britain, but a snapshot of ten lives whose detail might otherwise be invisible to society. The drama of their stories is at times more far-fetched than anything a novelist could come up with. I hope that putting their personal struggles and triumphs on paper may help promote empathy with the migrant experience of coming to Britain.

Journalists rarely get the chance to return to the people they interview let alone spend days on end in their company. The intensity of a project like this forces you to tread a fine line between reporting and friendship. Though I risk offending new friends, I have endeavoured to keep these portraits as faithful as any one-off interview.

Almost everyone in this book wanted their name to be published. A few were worried about the impact it might have on their immigration status and chose not to print their surnames. In two chapters, the names in the story have been changed to respect their privacy.

These ten people share many common experiences: the struggle to reach Britain and stay here; the tug of two homes; battling with the inefficiency of a Home Office recently declared unfit for purpose; the slog of work and the pain of separation from those they love. But once you hear any of these stories in depth it is the differences that stand out. These differences are what make them human. They have the power to transform each person in the eyes of a sceptical public from immigrant to individual.

London, March 2015

CHAPTER 1

The bus

I n Bucharest, a new life in western Europe begins at 4am in a draughty waiting room opposite McDonalds. It is one of thousands of locations around the world drab, prosaic and exotic where the long journey to Britain starts.

As the first four coaches of 2014 line up under floodlights, crowds of families gather to send off their relations on a long journey across the continent. The names of European cities are barked out and luggage-laden people shuffle forward, tickets in hand. The busiest bus is going to Hamburg, closely followed by others to Paris and Zurich.

The first coach to London in the New Year a 52-hour journey was expected to be the moment that a flood of migrants to Britain materialised. Excitable newspapers reported for weeks beforehand that Romanians unfettered access to working visas would result in a mass invasion, with coach loads arriving daily.

But only one person getting on at the start of Eurolines route 441 is going all the way to London.

Most are off to Germany, Belgium and Holland where work restrictions for Romanians and Bulgarians have also been loosened, seven years after the countries joined the EU.

Mihai drags his suitcase into the hold and climbs aboard. He is 29 and has been working in construction in London for the last year without papers. His shaved head makes him look tough in the half-light, but his easy smile dispels the image quickly.

For Mihai the biggest change in 2014 is not the first opportunity to work in Europe but his first chance to get the minimum wage. Because I dont have papers the bosses take advantage, he says. When I first came to the UK a Romanian man lied to me. When the boss paid us on Fridays, everybody else had their pay in an envelope but mine wasnt. I found out this guy had taken my envelope and was taking his cut from it so I only got 50. We had a fight and I never got my money back. He made me steal copper pipes from sites and take them to the Caledonian Road. I told the boss about his stealing and now he is gone and I get paid directly.