FOR DAI JIANJUN AND EVERYONE AT THE DRAGON WELL MANOR IN HANGZHOU AND THE AGRICULTURAL ACADEMY IN SUICHANG, WITH LOVE AND GRATITUDE

Oh beautiful South, whose scenery I once knew so well

Those flowers lit redder than flames by the sun rising on the river

Those waters in springtime, green as the leafy indigo that lines the banks

How could I ever forget Jiangnan?

From Memories of Jiangnan by Bai Juyi (772846 AD)

,

If you are going to follow links, please bookmark your page before linking.

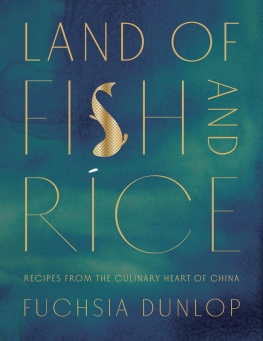

In this book, Id like to take you on a journey to Chinas beautiful Lower Yangtze region, known in Chinese as Jiangnan or south of the river. In the West, Jiangnan is known mostly for the modern metropolis of Shanghai, and yet Shanghai is just the gateway to a broader region that has been renowned in China for centuries for the beauty of its scenery, the elegance of its literary culture, the glittering wealth of its cities and the exquisite pleasures of its food. Jiangnan spans the eastern coastal provinces of Zhejiang and Jiangsu, the city of Shanghai and that part of southern Anhui province once known as Huizhou. In China, the region is known as a land of fish and rice ( yu mi zhi xiang ), blessed with a warm and nurturing climate, fertile land, and lakes, rivers and coastal waters that teem with fish and seafood.

My own journey there began nearly a decade ago, when I visited the old gastronomic capital of Yangzhou, and, like the Qing emperors more than two centuries before me, was captivated by its gentle way of life and glorious cuisine. Over the next few years, I made further forays into the region, visiting ancient cities including Hangzhou, Suzhou, Ningbo and Shaoxing and returning often to the modern capital, Shanghai. I wandered through old city lanes, with their street stalls and merchants mansions, and sojourned in kitchens in all kinds of places. With local chefs and farmers, I went out fishing on lakes and foraged in the countryside for bamboo shoots and wild vegetables.

I cant remember exactly when the idea of writing a Jiangnan cookbook seeded itself in my mind, but I know that it began to grow in earnest after I walked through a moongate into the enchanted garden of the Dragon Well Manor restaurant on the outskirts of Hangzhou. There, maverick restaurateur Dai Jianjun (otherwise known as A Dai) had created a sanctuary for the kind of Chinese cooking I had often dreamed of but rarely encountered. His team of buyers were scouring the countryside for radiantly fresh produce and foodstuffs made by artisans who were preserving traditional skills. In the kitchens, his chefs were cooking in the old-fashioned way, making their own cured meats and pickles and using fine stocks instead of MSG. It seemed to me that the Dragon Well Manor was restoring to Chinese cuisine its rightful dignity, as an expression of the perfect marriage between nature and human artifice and the ideal balance between health and pleasure.

With the support and encouragement of Dai Jianjun and other leading figures in the local food scene, I fell in love with the region and its extraordinary gastronomic culture, just as I had with Sichuan a decade before. I returned often to Jiangnan over the following years, seeking out chefs, home cooks, street vendors and farmers with stories to tell and recipes to teach, and tasting some of the most wonderful food I have ever encountered. No one who has fallen in love with Jiangnan ever wants to leave. In the fourth century, the official Zhang Han is said to have abandoned his post in the north of China because of his longing for the water shield soup and sliced perch eaten in his hometown there; ever since, thinking of perch and water shield ( chun lu zhi si ) has been shorthand in Chinese for homesickness. While every Chinese cuisine has its charms, from the dazzling technicolor spices of the Sichuanese to the belly-warming noodle dishes of the north, I know of no other that can put ones heart so much at ease as the food of Jiangnan.

Within China, the regions food is known for its delicacy and balance. Jiangnan cooks like to emphasize the true and essential tastes ( ben wei ) of their ingredients, rather than to mask them in a riot of seasonings. Traditionally, they favor gentle tastes, which are described in Chinese by the beautiful term qing dan . Often translated unappealingly into English as bland or insipid, it has no such pejorative meaning in Chinese: the word combines the two characters for pure and light and expresses a mildness of taste that refreshes and comforts, restoring equanimity to mind and body. This appreciation of culinary understatement is just one facet of a culture that also prizes the landscape blurred by mist, the impressionistic poem or painting, the winding path and the softness of a rainy day.

The generally even temperament of Jiangnan cooking does not imply any aversion to rich and delicious flavors. Indeed, the region is famed for its red-braised dishes, in which soy sauce, rice wine and sugar are combined to spectacular effect, for its fragrant vinegars and boozy drunken delicacies, and for a plethora of funky fermented foods. Overall, though, a good Jiangnan meal should leave a person feeling shu fu comfortable and well. For, as any Chinese person knows, a balanced diet is the foundation of good health, and a good cook is a kind of physician ( chu dao ji yi dao , the way of the chef is the way of the doctor). Heavy, meaty dishes and pungent flavors should be enjoyed in moderation and counterbalanced by lightly seasoned vegetables, cleansing broths and plain steamed rice.

Jiangnan cooking ranges from rustic food and street snacks to banquet delicacies so elaborate they are known as Kung Fu dishes ( gong fu cai )that is, dishes that demand the same level of technical mastery as the martial arts. It embraces myriad flavors, from the understated beauty of steamed fish and plain stir-fried greens to the outrageous pungency of stinking tofu. Even within the region there are striking differences in style, from the sweetness of Suzhou and Wuxi cooking to the fermented tastes of Shaoxing and the bright, clean seafood dishes of Ningbo. Jiangnan also has a notable tradition of Buddhist vegetarian cooking and a multitude of dainty dim sum snacks (or dian xin , as they are known in Mandarin). Famous local dishes are legion. They include beggars chicken, the whole bird stuffed and roasted in a carapace of lotus leaves and mud; the incomparable Dongpo pork; lions heads, the Platonic ideal of meatballs; dainty stir-fried shrimp with Dragon Well tea leaves; and drunken chicken steeped in an alcoholic brine. The origins of many delicacies are bound up with historical figures or embellished by intriguing legends.

Local people believe they enjoy the finest food in the country. Whereas Cantonese food, they say, is too raw and wild, Sichuanese is too hot and northern cooking is too salty, the food of Jiangnan is both so varied that one never tires of it and so harmonious that it calms the mind as well as the palate. In the opinion of many locals, their food is perfectly balanced, particularly healthy and has universal appeal, which is why it has for so long played a leading role in Chinese state banquets and diplomacy. Jiangnan food also strikes a chord with modern Western tastes because of its clean, light flavors, the emphasis on health and seasonality, the love of fermented foods and the use of meat in moderation as part of an everyday diet rich in vegetables.

Next page