Elfenbein - The Gist of Reading

Here you can read online Elfenbein - The Gist of Reading full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: Stanford;Calif, year: 2018;2017, publisher: Stanford University Press, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Gist of Reading

- Author:

- Publisher:Stanford University Press

- Genre:

- Year:2018;2017

- City:Stanford;Calif

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Gist of Reading: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Gist of Reading" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Gist of Reading — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Gist of Reading" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

THE GIST OF READING

Andrew Elfenbein

STANFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS

STANFORD, CALIFORNIA

Stanford University Press

Stanford, California

2018 by the Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University. All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system without the prior written permission of Stanford University Press.

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free, archival-quality paper

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Elfenbein, Andrew, author.

Title: The gist of reading / Andrew Elfenbein.

Description: Stanford, California : Stanford University Press, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017007207 | ISBN 9781503602564 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781503603851 (pbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781503604100 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Books and readingPsychological aspects. | Books and readingHistory19th century.

Classification: LCC Z1003 .E46 2017 | DDC 028/.9dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017007207

Typeset by Bruce Lundquist in 10/14 Minion Pro

For Textgroup, past, present, and future

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

What interdisciplinarity feels like: traversing the length of campus in subzero weather to meet with your collaborators; writing embarrassed notes to your statistics teacher explaining that you did not notice the last problem on the homework; resigning yourself to the fact that everyone else in the room will interpret a complex interaction graph more easily than you will; spending a shocking amount on updating SPSS; patiently explaining (again) why psychology can be useful. Luckily for me, I have worked with a remarkable group of psychologists, who made the benefits of interdisciplinarity outweigh its challenges.

My first thanks go to Paul van den Broek, who invited me to audit his class when I inquired about reading comprehension in psychology; that was the beginning of a long journey and an important friendship. Through Paul I came to know past and present members of Textgroup at the University of Minnesota, and I dedicate this book to them. Particular thanks go to Sashank Varma, David Rapp, Elaine Auyoung, Brooke Lea, Randy Fletcher, Sid Horton, Mike Mensink, Panayiota Kendeou, Catherine Bohn-Gettler, Reese Butterfuss, Mark Rose, Ben Seipel, Virginia Clinton, Andreas Schramm, Mary Jane White, Mija Van Der Wege, Sarah Carlson, and Katrina Schliesman. Sashank, David, and Brooke offered superb advice about this book and corrected many of my errors. Elaine is a treasured colleague, and being able to discuss this book and her own work has been a joy.

As I have presented my work, especially at the Society for Text and Discourse, I have received interest and support from many, especially Walter Kintsch, Arthur Graesser, Susan Goldman, Danielle McNamara, Joseph Magliano, Keith Millis, and John Sabatini. Richard Gerrig deserves a special mention for his detailed, critical commentary on several chapters. Patient instructors at the University of Minnesota introduced me to inferential statistics: Mark van Ryzin, Michelle Everson, Robert delMas, Andrew Zieffler, Michael Harwell, and Michael Rodriguez. Chairs of English at the University of Minnesota have supported this project: Michael Hancher, Paula Rabinowitz, and Ellen Messer-Davidow. Leslie Nightingale, Trent Olsen, and Katelin Krieg were excellent research assistants for tracking Victorian readers; Douglas Addleman has been exceptional in preparing the final manuscript. Emily-Jane Cohen at Stanford University Press has, once again, been a model editor, and I am lucky to have benefited from the careful copyediting of Joe Abbott.

Several scholars have invited me to present my work: Alan Liu at the University of California, Santa Barbara, Catherine Robson and James Eli Adams for the Dickens Universe, Elaine Scarry at Harvard, Asha Varadharjan at Queens University, Gerald Cohen-Vrignaud at the University of Tennessee, Charles Rzepka at Boston University, Leigh Dale and Jennifer McDonell at the University of Wollongong, Amy Muse for the International Conference on Romanticism, and Alan Bewell at the University of Toronto; I am also grateful to audiences at conferences organized by the North American Victorian Studies Association and the Dickens Universe. I have been fortunate to have the support and friendship of Susan Wolfson, Herbert Tucker, and Deidre Lynch; Alan Richardson deserves special mention for his pioneering work on cognitive science and literature and his early encouragement of my work.

Sabbatical fellowships from the American Philosophical Society and the American Council of Learned Societies have made this book possible, as well as travel grants and grants-in-aid from the College of Liberal Arts at the University of Minnesota. Earlier versions of portions of this book appeared in PMLA, MLQ, and A Companion to the English Novel, edited by Stephen Arata, Madigan Haley, J. Paul Hunter, and Jennifer Wicke (New York: Wiley-Blackwell, 2015). I am grateful to all for permission to republish; Leane Zugsmiths The Three Veterans appears in an appendix to .

Several cats past and present have woven themselves into my life as I wrote: loving but troubled Muffin, regal Brandy, and now Charlotte, who inspires me with a clear sense of priorities. My son, Dima, has grown into a man in the time it has taken me to write this, and I could not be more proud. After thirty years of living with me, my husband John Watkins remains my sharpest critic, and I thank him for supporting me as my career has taken directions that neither of us could have anticipated.

INTRODUCTION

INTERDISCIPLINARITY

I, Too, Dislike It

DISSATISFIED with discussions of reading in literary criticism, I became interested in how cognitive psychologists understood it. As I became acquainted with a new field, I found myself tripping over a stumbling block that took me a while to identify. Objections that seemed smart to me seemed beside the point to the psychologists with whom I studied. The difference in viewpoints arose from a core disciplinary distinction between us about the value of the particular versus the general. As a literary scholar, I sided with the particular. Although I could generalize about periods like romanticism, genres like the ode, or the oeuvre of an author like Byron, the core of my expertise was discussing what made a text, line, word, or even phoneme special. Literature consisted of irreducible particularities, and my job was to recognize them. Without sensitivity to them, there seemed no reason for scholarship at all.

When I came to study psychology, I confronted a different outlook; in Ellen Messer-Davidows words, the schemes of perception, cognition, and action that practitioners must use were not the ones I knew.

My irritation came from psychologys probabilistic claims, which describe general tendencies across a wide variety of individuals that are often, though not always, true. Especially since I, as an academic critic, did not represent a general reading population, I felt that psychological findings about reading did not describe me. What I learned was that it was a mistake to dismiss psychological findings for this reason. Instead, they had great value in capturing widely shared aspects of reading across a huge variety of readers and were useful for someone like me, who cared about reading and its history. More importantly, the difference between my reading and that described in psychological articles was not as vast as I had first believed. I had developed, through long practice, a set of strategies for understanding imaginative literature, but the cognitive architecture underlying these strategies was shared with many readers. I just had sharpened a certain subset of them, so that my reading shifted between strategies common to many readers and those belonging to literary scholars. Psychological vocabulary was especially helpful in understanding my challenges when faced with difficult or unfamiliar texts, moments at which my accustomed modes of reading were less helpful than I hoped.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

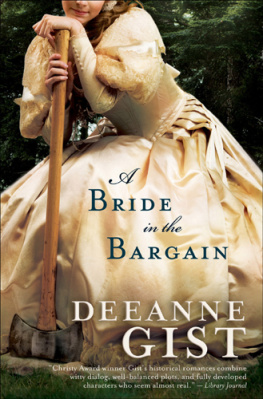

Similar books «The Gist of Reading»

Look at similar books to The Gist of Reading. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Gist of Reading and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.