Acknowledgements

I am deeply indebted to Mark Glubke at Applause Books for acquiring this anthology as well as for providing crucial input at its inception. I also wish to thank authors Alysia Abbott, John Clum, Mart Crowley, Stephen Fife, Joe E. Jeffreys, Ken Furtado, Esther Harriot, Sheridan Morley, Caraid OBrien, and Don Shewey for helping point me in the right direction.

Kaier Curtins We Can Always Call Them Bulgarians and Alan Sinfields Out on Stage have both been invaluable resources in my research, especially considering the dearth of literature on gay and lesbian drama during the early twentieth century.

My own personal editor, Brad Hampton, and friends Epitacio Arganza, Nicole Boyd, Liz and Ron Briggs, Jason Cicci, Tim Deak, Juliet Furness, Laura and Tommy Hanson, Bob and Renee Isely Tobin, Aaron and Gretchen Kerr, Gail Miller, Carolyn and David Rapp, Hannah Richman Slosberg, Wilson Valentin, Rachel Werbel, and Robin Whitehouse, have all dispensed wise advice and provided unfaltering support as well as intermittent opportunities for rest and relaxation.

Kenyon Harbison at the William Morris Agency, Buddy Thomas at ICM, Caryn Burtt at Random House, and Rick Miramontez at the Richard Kornberg Office have all gone above and beyond the call of duty in processing permissions requests.

Theatre World editor John Willis, my mentor and friend, continues to teach me the value of the work we do as archivists and historians through our Theatre World annuals, as well as the proper way to do it, and also generously granted me unlimited access to his vast archive.

The indefatigable staff of the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts at Lincoln Centerespecially Jeremy Megrawhas been indispensable in providing assistance with tracking down elusive photographs and production information.

At Applause Theatre and Cinema Books, managing editors Kallie Shimek and Jenna Bagnini have both been incredibly valuable in helping determine which titles would ultimately be included in this anthology, and have continued to provide encouragement toward its successful completion. Michelle Thompsons thoroughly captivating cover design and editorial advice were crucial to the actualization of this publication, as was publicist Kay Radtkes public relations expertise. John Cerullo and Michael Messina have guided this project from its infancy, assuring that it received the attention it required, as they do on an ongoing basis with our Theatre World series.

To all of the above, I am forever grateful.

BEN HODGES is associate editor to John Willis on Theatre World, the definitive pictorial and statistical record of the American theatre, and serves as executive producer of the Theatre World Awards, the oldest awards given for Broadway and Off-Broadway debuts. He is an actor, director, and producer, and has worked as a casting director for the theatre, television, and film. He currently serves as executive director for Fat Chance Productions and the Ground Floor Theatre in New York City and is vice president of Fat Chance Films. Ben received his B.F.A. in Acting/Directing from Otterbein College. He lives in New York City.

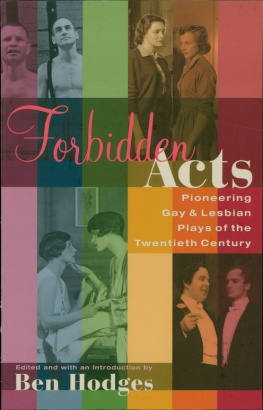

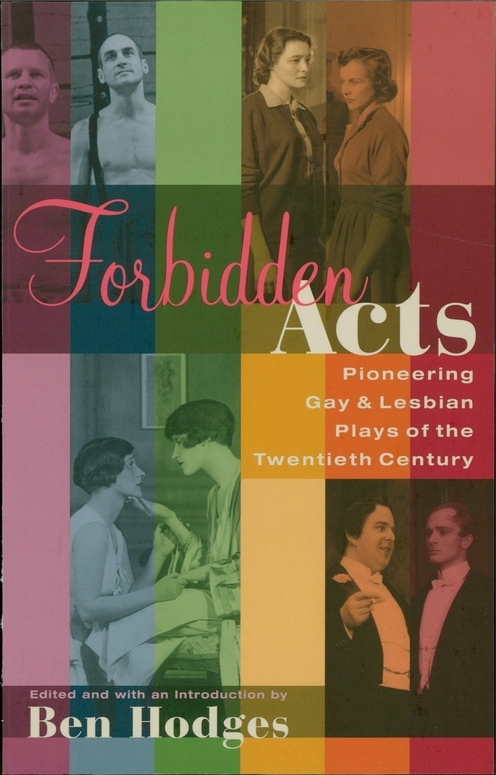

Cover photos, clockwise:

Patricia Neal (Karen), and Kim Hunter (Martha) in The Childrens Hour, at the Coronet Theatre (revival), 1952. (Photo by Eileen Darby. Reprinted with permission from the John Willis Theatre World/Screen World Archive.)

Robert Morley (Oscar Wilde) and John Buckmaster (Lord Alfred Douglas) and in Oscar Wilde, at the Fulton Theatre, 1938. (Photo reprinted with permission from the Billy Rose Theatre Collection, The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations.)

Ann Trevor (Gisele) and Helen Menken (Irene) in The Captive, at the Empire Theatre, 1926. (Photo reprinted with permission from the Billy Rose Theatre Collection, The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations.)

Michael York (Max) and Jeffrey DeMunn (Horst) in Bent, at the New Apollo Theatre, 1980. (Photo by Jody Caravaglia. Reprinted with permission from the John Willis Theatre World/Screen World Archive.)

Preface

The birth of Yiddish literature in Russia and the beginning of the great Jewish exodus from that country to America are two effects of one and the same cause. The same anti-semitic crusade that forced the Children of Israel to go beyond the seas in search of a safe home, aroused them to a new sense of their racial self-respect and to an unwonted interest in their native tongue.

Prior to the anti-Jewish riots of 1881 educated Jews were wont to look upon their mother tongue as a jargon beneath the dignity of cultured attention. Yiddish, more especially in its written form, was the language of the untutored. People with modern training spoke and wrote Russian. As for the intellectual class of the Talmudic type, it would carry on its correspondence and, indeed, write its essays, verse and fiction, in the language of Isaiah. One wrote Yiddish to ones mother, for the mothers of those days were not apt to understand anything else. For the rest, the tongue of the Jewish masses was never taken seriously and the very notion of a literature in a gibberish that has not even a grammar would have seemed ludicrous.

Popular stories and songs were written in Yiddish long before the end of the nineteenth century, but, barring certain exceptions, these were intended exclusively for the most ignorant elements of the populace, and were contemptuously described as servant-maid literature. (As for Yiddish poetry, it was almost wholly confined to the purposes of the wedding bard.) The exceptions here mentioned belong to the sixties and the seventies, when some brilliant attempts were made in the direction of literature in the better sense of the term by S. J. Abramovitch. But Abramovitchs stories were not even regarded as vanguard swallows heralding the approach of Spring. They aroused an amused sort of admiration. Indeed, it required a peculiar independence of mind to read them at all, and while they were greeted with patronizing applause, it was a long time before they found imitators.

All this changed when the whip of legal discrimination and massacres produced the national awakening of the educated Jew. Thousands of enlightened men and women then suddenly made the discovery, as it were, that the speech of their childhood was not a jargon, but a real language,that instead of being a wretched conglomeration of uncouth words and phrases, it was rich in neglected beauty and possessed a homely vigor full of artistic possibilities. A stimulus was given to writing Yiddish as the Gentiles do their mother tongues. Abramovitch was hailed as the father of Yiddish literature and his example was followed by a number of new writers, several of whom proved to be men of extraordinary gifts.

The movement bears curious resemblance to that of the present literary renaissance of Ireland.

Some truly marvelous results were soon achieved, the list of writers produced by the new literature including the names of men like Rabinovitch (Sholom Aleikhem) and Peretz, whose tales were crowned with immense popularity.

Sholom Asch belongs to a younger group of Yiddish story-tellers and now that Abramovitch, Rabinovitch and Peretz are in their graves (they have all died during the last two years) he is the most popular living producer of Yiddish fiction.