Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For my dad, Greg Briody

Memories are long in the western Dakotas. Maybe its the winters, which give people time to brood, people who bear the pain of living in a harsh, unforgiving climate. Hurts linger.

Kathleen Norris, author of Dakota: A Spiritual Geography

W elcome to the corner of Oil Avenue and Energy Street.

This is my home for the summer. It consists of a 2001 pop-up camper with 150 square feet of living space, a fold-up dining room table, and bathroom walls built only from particle board. I can see my neighbors TV screen from my kitchen sink, and their 10-month-old daughter crying at the doorstep. Semi trucks rumble by every few minutes, kicking up dust and sending clouds of dirt into my eyes. Grassy plains stretch for miles on either side of the road.

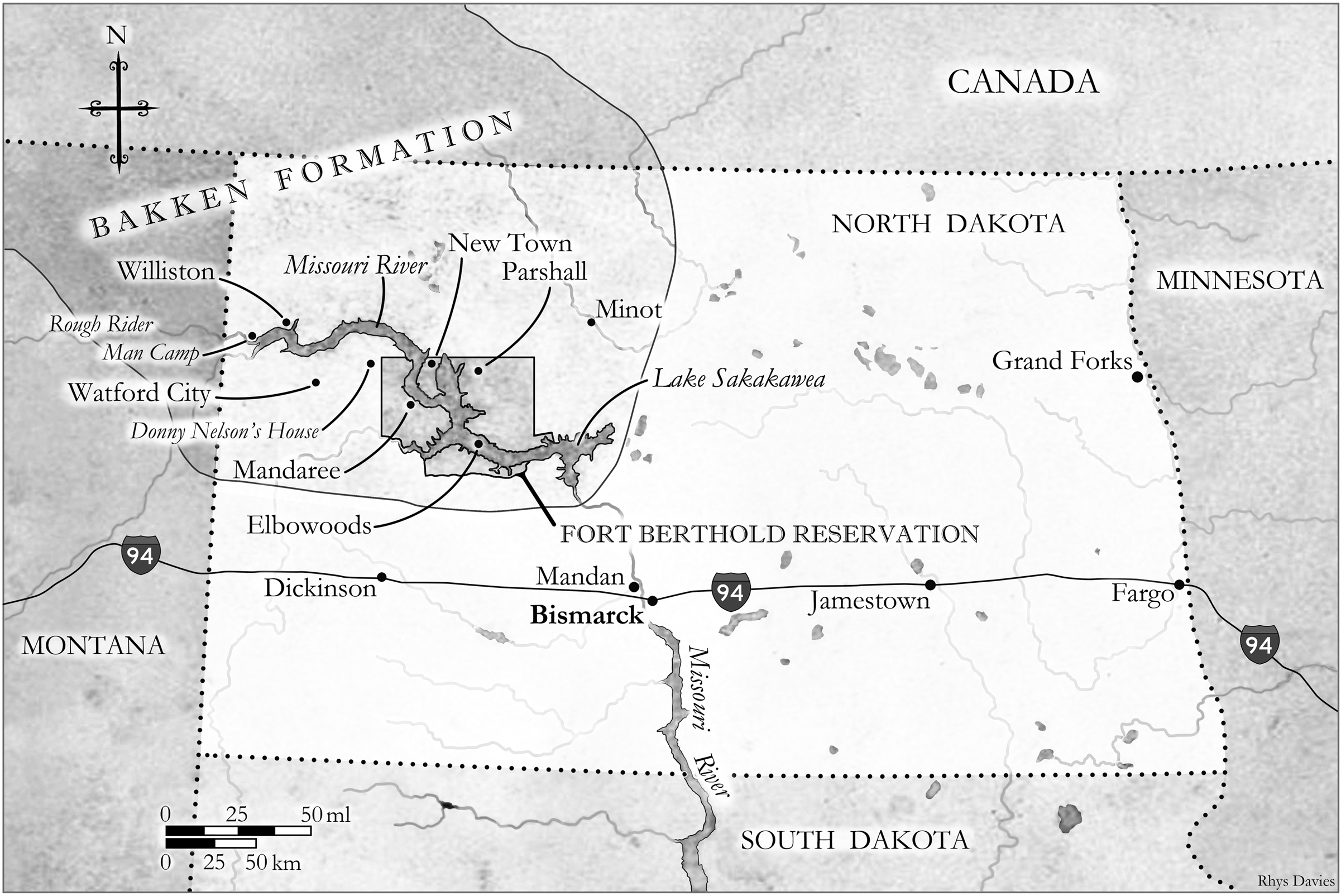

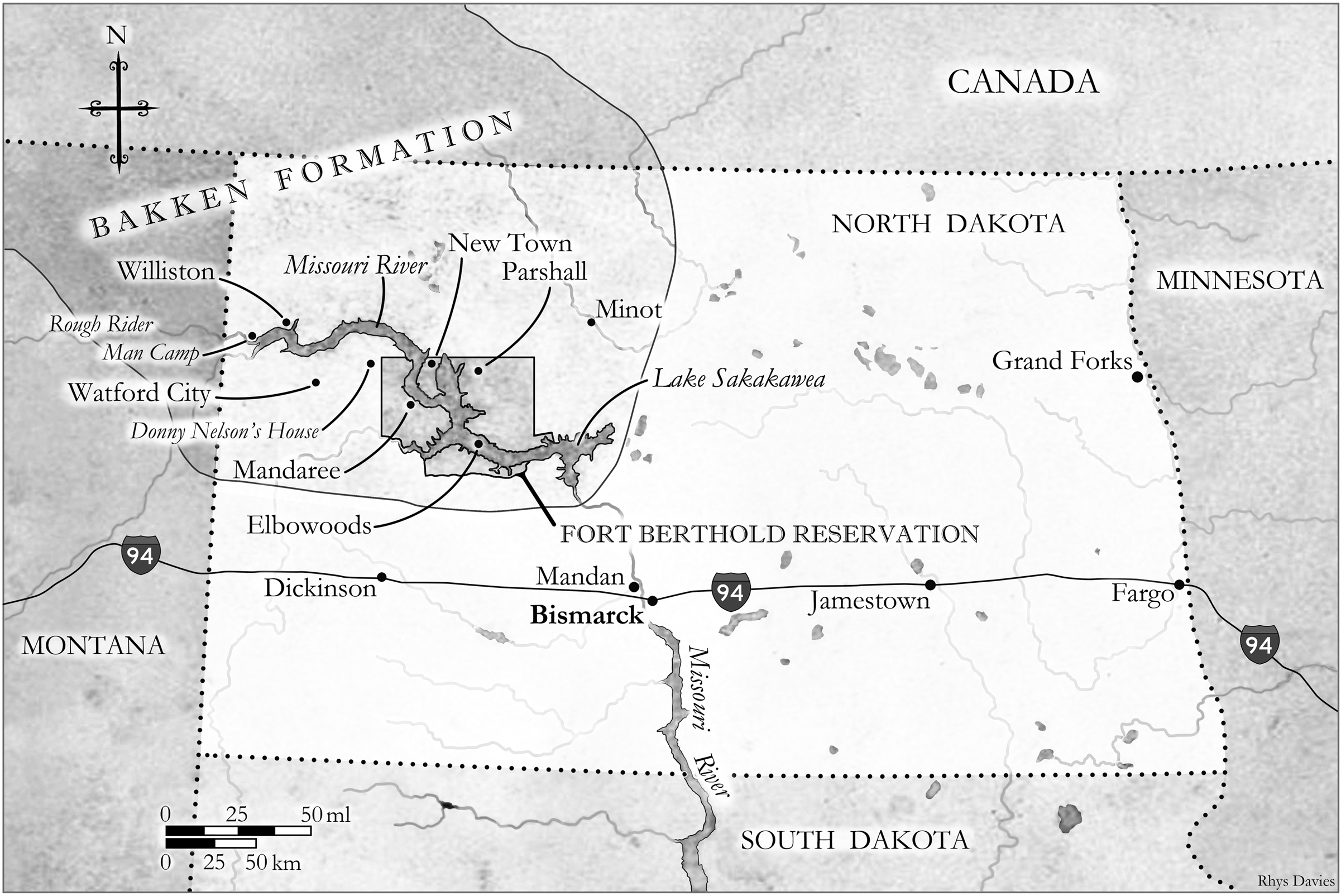

Im living in a trailer park on the outskirts of a town called Williston, North Dakota, about 60 miles south of the Canadian border, at the epicenter of one of the largest oil booms the United States has ever experienced.

Six years earlier, in 2007, this was a sleepy prairie town where it was unheard of to lock your doors at night, and the elementary school almost shut down because of declining enrollment. But in the past few years, the towns population has tripled as thousands of workers, mostly young men, have come looking for opportunity. Yesterday, the local paper reported that a woman was shot in the parking lot at Walmart. My trailer park landlord, a gristly woman in her late 40s, told me not to go out after sunset, and thereve been rumors that theres been another rape downtown. I always carry this on me, the 19-year-old girl working at the gas station tells me, gesturing to the knife strapped to her belt, the holster unhooked.

At a bar last night, a man I was talking with reached over and started touching my leg. I jumped up, paid the bill, and left, shaken. I had to walk past a crowd of burly oil workers standing outside smoking cigarettes. I felt their eyes on me as I hurried to my car.

Everyone I talked to warned me this place wasnt safe for a 29-year-old woman, but yet, I still came. I wanted to know what happens when a small town is transformed overnight into a bustling, nearly all-male metropolis. I wanted to see it for myself. So here I am.

On a sunny Monday afternoon in early September 2013, I sat in the passenger seat of Donny Nelsons dark blue Ford pickup truck, heading along a bumpy dirt road. Nelson drove and his small, shaggy dog, Lucky, perched on the leather divider between us. The clouds overhead extended for miles across the horizon, shifting and dancing along the curves of grassy hills.

A country singer crooned on the radio as Nelson stared out his window. Hed been explaining how he ended up with the oil rigs around his home. It had to do with mineral rights, and the fact that he didnt own what was below his property. We passed a pipeline construction site on the left. The side of the hill was carved out, revealing a wall of black dirt. Four yellow CAT excavators sat in a line like they were prepping for battle.

Nelsons farmland was one of the most beautiful parts of North Dakota Id seen so far. Id been living in oil country for two months, and my impression of the area was that it had become a wasteland. Id seen more traffic, dust, and heavy industry than in any major metropolitan city Id visitedin a state that, a mere three years before, had the third-lowest population in the United States. But this area of North Dakota was different. It was part of the Badlandsinstead of flat prairie, rolling hills and eroded rock formations speckled the golden landscape. Theodore Roosevelt, who lived in North Dakota as a young man, once described the Badlands as so fantastically broken in form and so bizarre in color as to seem hardly properly to belong to this earth.

As Nelson talked, he leaned forward in his seat, looking off into the distance. Do you see that smoke? he asked, pointing to the hills on the left. I saw nothing at first, but as I stared at the spot he was gesturing at, I saw gray smoke billowing up into the sunny sky.

Nelson drove faster, and Lucky sat up, sensing something was wrong.

I definitely smell smoke, said Nelson. Its right in the middle of my pasture.

We curved around a corner, and I held onto the door to keep from sliding. Nelson navigated the truck off the dirt road and onto the hilly pasture. My head almost hit the top of the cab. Finally we saw the source of the smoke: It was coming from an oil well site on Nelsons land.

Nelson pulled up and stepped out of his truck, and I followed. About six Hess employees stood around the singed grass, with one guy hosing it down. The smoke from the blackened patch floated up in thin strands into the blue sky.

One guy recognized Nelson and walked over. Hi, Donny, sorry about this. A bulldozer hit a rock and created a spark. Luckily we saw it before it got too bad.

Nelson nodded, looking frustrated. He knew the guy, he told me later. He was a local. Nelson told them to update him if anything else happened, and we went on our way. As you can see, nobody called the fire department, he said as we lifted ourselves back into the truck. I learned later that the fire was never reported and Nelson didnt receive compensation for the damage. Although he tried to be patient with the workers, knowing it wasnt always their fault, he wanted them to be respectful of his home. If they didnt tell me about it, Id make them pay, he said. Because then you just get mad.

Nelson is 49 years old and owns about 8,000 acres of farmland, growing peas, oats, barley, durum, flax, and corn, and raises cattle, in what used to be in one of the most remote areas of the country. The entire 23,000-acre area he lives on has fewer than 10 families. Nelson went to elementary school with Wanda Leppell down the road, and almost every day he stops by the house of his neighbor Roger, whom hes known most of his life, to see how hes doing. When I visited Nelson, my GPS couldnt locate his address, so he gave me directions by providing the mile marker for his dirt road.

Nelsons grandfather came to North Dakota from Minnesota during the Homestead Act in the early 1900s. He took the train carrying a few suitcases of supplies to the small town of Tioga, 70 miles from Nelsons farm, and had to wait until the Missouri River froze over to cross it. He came over this hill right behind my house, Nelson said, pointing, and said, This is where Im going to stay.

The original farm is along Clark Creek (Nelson pronounces it Clark Crek), which was discovered by explorers Lewis and Clark. Nelson grew up working on the farm. His father never had hired help, so as a small child, Nelson hauled water, pitched hay, and rode in his fathers old Minneapolis-Moline tractor. His older brother did the tougher jobs. His father would strap his brother into a second tractor, stick it in gear, and tell him to turn off the key if he ran into any problems. Everybody did stuff like that, said Nelson.