Text: Nathalia Brodskaia and Viorel Rau

Translation: Mike Darton (main text), Nick Cowling and Marie-Nolle Dumaz (biographies)

Layout:

Baseline Co. Ltd

61A-63A Vo Van Tan Street

4 th Floor

District 3, Ho Chi Minh City

Vietnam

Parkstone Press International, New York, USA

Confidential Concepts, worldwide, USA

Fernando De Angelis

Onismi Babici

Branko Babunek

Andr Bauchant, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, USA/ ADAGP, Paris

John Bensted

Camille Bombois, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, USA/ ADAGP, Paris

Ilija Bosilj-Basicevic

Janko Braic

Aristide Caillaud, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, USA/ ADAGP, Paris

Camelia Ciobanu, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, USA/ Visarta, Bucarest

Gheorghe Coltet

Mircea Corpodean

Viorel Cristea

Mihai Dascalu

Adolf Dietrich, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, USA/ Pro Litteris, Zrich

Gheorghe Dumitrescu

Jean Eve, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, USA/ ADAGP, Paris

Francesco Galeotti

Ivan Generalic

Ion Gheorge Grigorescu

Art Morris Hirshfield/ Licensed by VAGA, New York, USA, pp.166, 167, 168-169

Paula Jacob

Ana Kiss

Nikifor Krylov

Boris Kustodiev

Dominique Lagru, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, USA/ ADAGP, Paris

Marie Laurencin, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, USA/ ADAGP, Paris

Antonio Ligabue

Oscar de Mejo

Orneore Metelli

Successi Mir, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, USA/ ADAGP, Paris

Gheorghe Mitrachita

COPYRIGHT Grandma Moses Properties Co., New York, p.170, 171, 172, 173

Ion Nita Nicodin

Emil Pavelescu

Ion Pencea

Dominique Peyronnet

Horace Pippin

Niko Pirosmani

Catinca Popescu

Ivan Rabuzin

Milan Raic

Ren Martin Rimbert

Shalom de Safed

Sava Sekulic

Sraphine de Senlis (Sraphine Louis), Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, USA/ ADAGP, Paris

Emma Stern

Gheorghe Sturza

Anuta Tite

Ivan Vecenaj

Guido Vedovato

Miguel Garcia Vivancos

Louis Vivin, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, USA/ ADAGP, Paris

Elena A. Volkova

Alfred Wallis, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, USA/ DACS, London

Valeria Zahiu

All rights reserved.

No parts of this publication may be reproduced or adapted without the permission of the copyright holder, throughout the world. Unless otherwise specified, copyright on the works reproduced lies with the respective photographers. Despite intensive research, it has not always been possible to establish copyright ownership. Where this is the case, we would appreciate notification.

ISBN: 978-1-78310-379-9

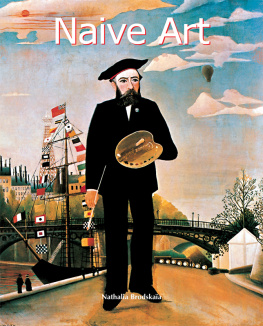

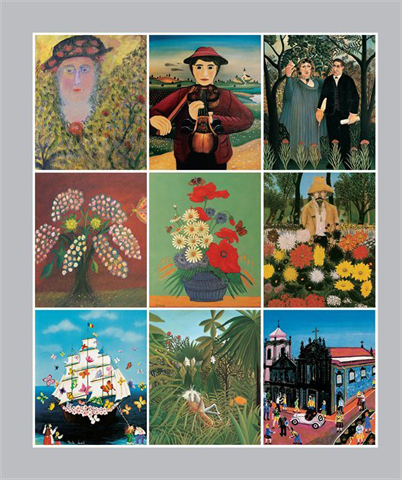

Naive Art

Contents

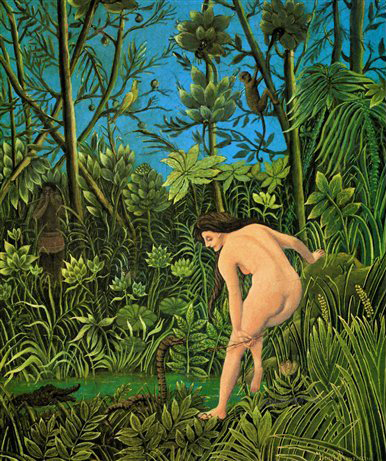

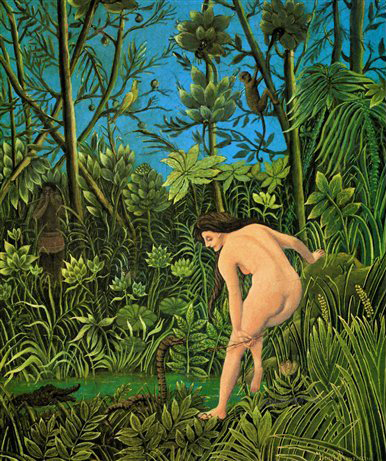

Henri Rousseau,

also called the Douanier Rousseau, The Charm, 1909.

Oil on canvas, 45.5 x 37.5 cm.

Museum Charlotte Zander, Bnnigheim.

I. Birth of Naive Art

When Was Naive Art Born?

There are two possible ways of defining when naive art originated. One is to reckon that it happened when naive art was first accepted as an artistic mode of status equal with every other artistic mode. That would date its birth to the first years of the twentieth century. The other is to apprehend naive art as no more or less than that, and to look back into human prehistory and to a time when all art was of a type that might now be considered naive tens of thousands of years ago, when the first rock drawings were etched and when the first cave-pictures of bears and other animals were scratched out. If we accept this second definition, we are inevitably confronted with the very intriguing question, so who was that first naive artist?

Many thousands of years ago, then, in the dawn of human awareness, there lived a hunter. One day it came to him to scratch on a flattish rock surface the contours of a deer or a goat in the act of running away. A single, economical line was enough to render the exquisite form of the graceful creature and the agile swiftness of its flight. The hunters experience was not that of an artist, simply that of a hunter who had observed his model all his life. It is impossible at this distance in time to know why he made his drawing. Perhaps it was an attempt to say something important to his family group; perhaps it was meant as a divine symbol, a charm intended to bring success in the hunt. Whatever but from the point of view of an art historian, such an artistic form of expression testifies at the very least to the awakening of individual creative energy and the need, after its accumulation through the process of encounters with the lore of nature, to find an outlet for it.

This first-ever artist really did exist. He must have existed. And he must therefore have been truly naive in what he depicted because he was living at a time when no system of pictorial representation had been invented. Only thereafter did such a system gradually begin to take shape and develop. And only when such a system is in place can there be anything like a professional artist. It is very unlikely, for example, that the paintings on the walls of the Altamira or Lascaux caves were creations of unskilled artists. The precision in depiction of the characteristic features of bison, especially their massive agility, the use of chiaroscuro, the overall beauty of the paintings with their subtleties of coloration all these surely reveal the brilliant craftsmanship of the professional artist. So what about the naive artist, that hunter who did not become professional? He probably carried on with his pictorial experimentation, using whatever materials came to hand; the people around him did not perceive him as an artist, and his efforts were pretty well ignored.

Any set system of pictorial representation indeed, any systematic art mode automatically becomes a standard against which to judge those who through inability or recalcitrance do not adhere to it. The nations of Europe have carefully preserved as many masterpieces of classical antiquity as they have been able to, and have scrupulously also consigned to history the names of the classical artists, architects, sculptors and designers. What chance was there, then, for some lesser mortal of the Athens of the fifth century B.C.E. who tried to paint a picture, that he might still be remembered today when most of the ancient frescos have not survived and time has not preserved for us the easel-paintings of those legendary masters whose names have been immortalised through the written word? The name of the Henri Rousseau of classical Athens has been lost forever but he undoubtedly existed.

The Golden Section, the canon of the (ideal proportions of the) human form as used by Polyclitus, the notion of harmony based on mathematics to lend perfection to art all of these derived from one island of ancient civilisation adrift in a veritable sea of savage peoples: that of the Greeks. The Greeks encountered this tide of savagery everywhere they went. The stone statues of women executed by the Scythians in the area north of the Black Sea, for example, they regarded as barbarian primitive art and its sculptors as naive artists oblivious to the laws of harmony.