INTRODUCTION

Hay, madre, un sitio en el mundo, que se llama Pars.

Un sitio muy grande y lejano y otra vez grande.

(There is, mother, a place in the world called Paris.

A very big place and far and very big again.)

Csar Vallejo

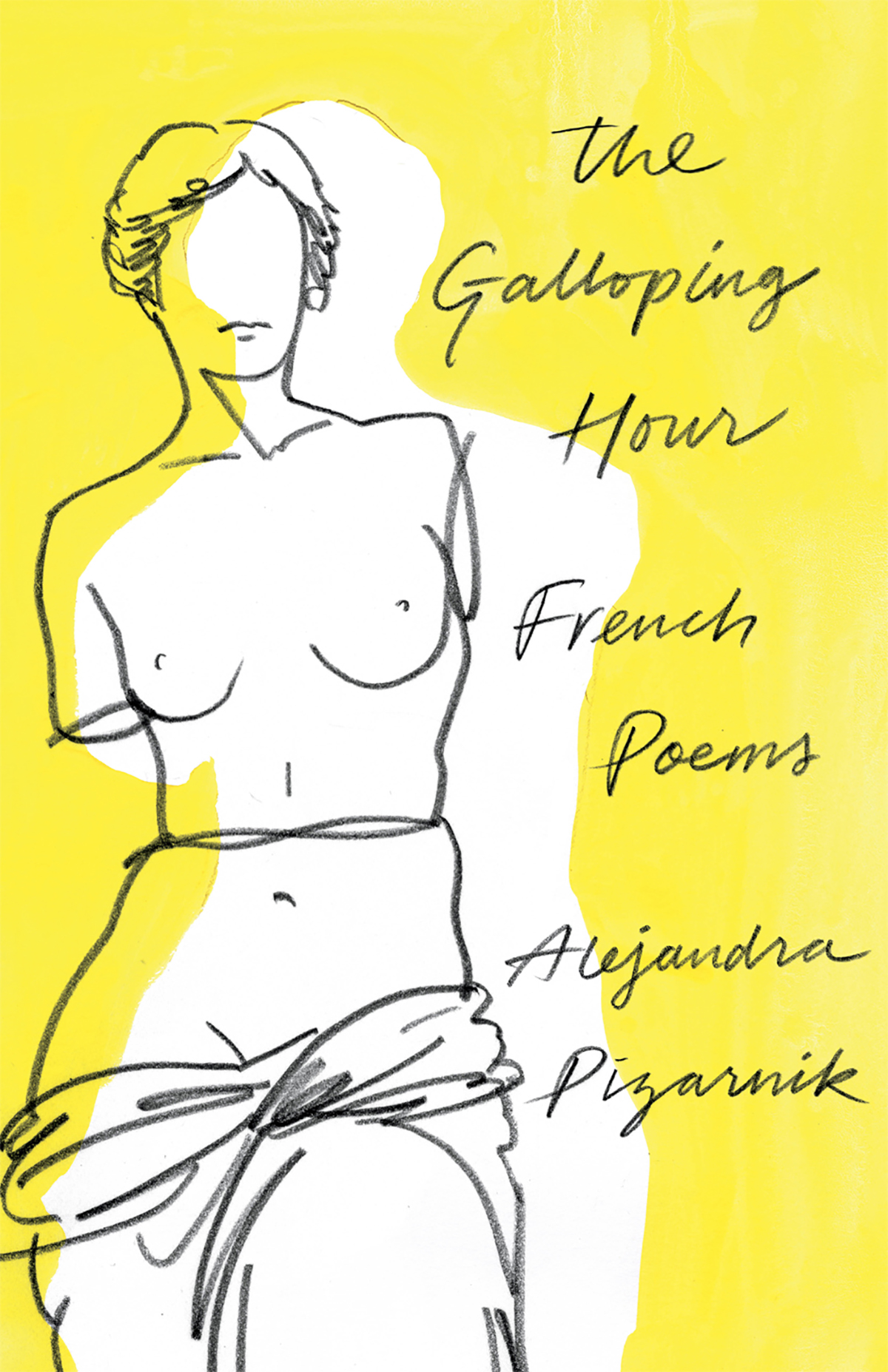

In a diary entry of May 1959, while still living with her parents in Buenos Aires, shortly after the publication of her third poetry collection, the twenty-three-year-old Alejandra Pizarnik wrote:

Je voudrais vivre pour crire. Non penser autre chose qu crire. Je ne prtend [sic] pas lamour ni largent. Je ne veux pas penser, ni construire dcemment ma vie. Je veux de la paix: lire, tudier, gagner un peu dargent pour mindependiser [sic] de ma famille, et crire.

(I would like to live in order to write. Not to think of anything else other than to write. I am not after love nor money. I dont want to think nor decently build my life. I want peace: to read, to study, to earn some money so that I become independent from my family, and to write.)

Bold and assertive in tone, these words are less of a confession than a daring conviction, a resolution, a literary plan. Circumstantial? Purposely stylized? Perhaps the more essential question here is: Why did the Argentinian-born poet turn to a foreign language that, until then, shed almost exclusively employed just to read French literature?

The younger of two daughters to Jewish immigrants who settled in Argentina during the 1930s, Flora Alejandra Pizarnik was born on April 29, 1936, in Avellaneda a port city located within the greater Buenos Aires metropolitan area. Her parents, Ela Pizarnik and Rejzla Bromiker de Pizarnik, had left Rwne, then part of Poland, two years earlier to flee the rising wave of antisemitism across Eastern Europe. The family spoke Yiddish and Spanish at home, and the two sisters, Myriam and Alejandra, attended a progressive Jewish school. Alejandra grew up among these two languages, along with the accepted Latin American notion of French of France as inseparable from high culture, especially for those with fine-art or literary aspirations.

After Pizarnik sketched out a literary plan, in the same spiral-bound gray Avon notebook, she noted:

Tengo que ir a Francia. Recordarlo. Recordar que debo quererlo mucho. Recordar que es lo nico que me queda por querer, en este mundo ancho y alto.

(I have to go to France. Remember it. Remember that I must want it badly. Remember that this is the only thing left to want, in this world wide and deep.)

Not many today would disagree that this obligation resulted from a condition, partially elective, partially brought on by historical pressures. A quick glance at the biographies of some of the great European and North and Latin American writers of the past century reveals, more often than not, a single beacon, a common destination one unrivaled city, sought after for its bohemian cultural scene.

By the early 1920s, with literary modernism at its apogee, Paris was the creative center of the western world, with Ezra Pound, James Joyce, and Csar Vallejo, to name but three, among the many foreign authors who took up residence there. The list is extensive. Some even abandoned their mother tongue and made French their writing language, as is the case of Vallejos compatriot Csar Moro, or, in the late thirties, the Romanian philosopher Emil Cioran one of the finest prose writers of the twentieth century in French. Paris lured the rich and the poor, the established and the aspiring, the singular and uninspired.

Within a few decades, the City of Light had become home to a large community of expatriate authors and artists from around the globe. The French capital and, to some extent, the genius of the French language came to be equated with a rite of passage the grand yet tangible myth.

In the aftermath of World War II, the heart of Paris welcomed those Latin American writers associated with the Boom and Post-Boom (Julio Cortzar, Mario Vargas Llosa, Severo Sarduy), as well as many nomadic writer-diplomats hailing from the other side of the Atlantic (Miguel ngel Asturias, Octavio Paz, Alejo Carpentier). By this time, a surrealist poetic current had spread across the New World; in Argentina, it circulated among a second generation of avant-garde Francophile artists and poets, including the Spanish painter Juan Batlle Planas (in whose atelier the young Alejandra Pizarnik briefly studied after dropping out of the University of Buenos Aires), the poet-painter Enrique Molina, and the poet Olga Orozco all of whom were friends with Pizarnik by the late 1950s.

Increasingly obsessed with her craft and her literary image, and encouraged by close friends, Pizarnik, who had relatives in France, became part of the draw of Paris. On March 11, 1960, without professional obligations or any real responsibilities, she embarked on the transatlantic Laenec. Not for a movement. Not for any theoretical school, but on a self-imposed literary exile. She departed for a city that was not the cultural museum it is today (many chose to live there with moderate or meager means). She left for Paris so big and vibrant and beautiful.

In the first few months, however, Pizarnik lived on the margins of the dreamed city. She arrived in the western suburbs, initially lodging in Chtenay-Malabry with one of her paternal uncles; then in Neuilly-sur-Seine with another one of her fathers brothers. Both were Jewish immigrants who had been forced to escape their native Poland three decades prior. Disappointed and dissatisfied, Alejandra knew she hadnt come to Paris just to duplicate her ordinary life in Buenos Aires.