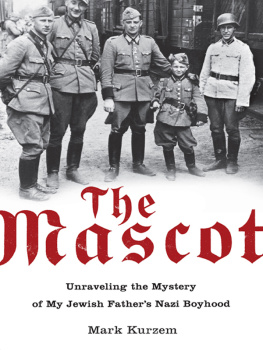

THE MASCOT

UNRAVELING THE MYSTERY OF MY JEWISH FATHERS NAZI BOYHOOD

MARK KURZEM

VIKING

VIKING

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A. Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3 Canada (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.) Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England Penguin Ireland, 25 St. Stephens Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd) Penguin Books Australia Ltd, 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd) Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi 110 017, India Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0745, Auckland, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd.) Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Published in 2007 by Viking Penguin, a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

Copyright Mark Kurzem, 2007

All rights reserved

ISBN: 978-1-1012-1386-5

Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book via the Internet or via any other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal and punishable by law. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrightable materials. Your support of the authors rights is appreciated.

In memory of my mother, Patricia Kurzem (19372003)

AUTHORS NOTE

T he story of my father, the mascot, is a true one. In order to protect the privacy of some of the individuals and organizations I encountered during my research over the years, I have altered various names and identifying details.

I have also condensed the chronology of my research in order to enhance the narrative flow of the book, but the actual sequence of events remains true and accurate. I beg my readers indulgence of these alterations, for they were made with their reading pleasure in mind.

In addition, there are various accounts of the Second World War, and, almost inevitably perhaps, discrepancies among historians versions of certain incidents in matters such as dates, locations, and the troops involved. An important case in point is the precise date of the Slonim massacre, which still remains unclear, as does whether my father witnessed the massacre, as reflected in this book. I also encountered inconsistencies in the recollections of some individuals who were direct witnesses to the events. Furthermore, there were considerable variations in the spelling of place-names. In the interest of clarity and consistency, I have adhered to one version at all times.

I have done my best to navigate these discrepancies throughout.

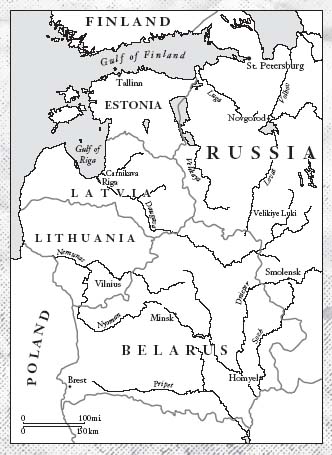

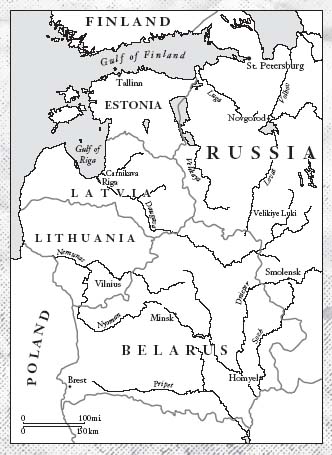

North-central eastern Europe.

THE MASCOT

PART I

CHAPTER ONE

THIS IS ALL THAT I KNOW

I f Im ever asked, Whats your father like? a simple answer always escapes me.

Even though I can look back on a lifetime spent in his company, I have never been able to take his measure: One part of him is a shy, brooding Russian peasant who shows a certain air of navet, if not gullibility, with strangers. Then there is another side: alert, highly gregarious, and astonishingly worldly.

His unexpected appearance on my doorstep in Oxford one May afternoon in 1997 left me more mystified than ever.

I was walking back to my digs, weighed down by books that Id just bought at Blackwells bookshop. I was looking forward to getting home and immersing myself in a new purchase, the door of my study closed to the world for several hours.

As I let myself in I noticed a scrap of paper that had been slipped under the door. It was the stub of a boarding pass for a flight from Melbourne. Written on its margin was OVER AT DAPHNES DAD .

I immediately recognized my fathers handwriting: he wrote only in capital letters and without any punctuation. He had always formed his sentences like this; hed grown up in eastern Europe during the Second World War and had had no formal schooling.

I was taken aback. I had spoken to my father on the phone only a couple of days earlier. He had been at home in Melbourne, watching television with my mother, and when I had asked how their week had been, all he would say was, Oh, its been the same as usual here, son. Nothing much happens in this neck of the woods.

His tone had not altered in the slightest nor had his voice missed a beat when I asked what they were planning for the coming week: No plans, really.

At that moment a slight clicking sound indicated that he had just turned on the speakerphone so that my mother could join in the conversation. He did this every time I called.

The three of us chatted on the phone for some time about things that had happened during the past week in Oxford, where I was a research student. We touched upon my plans to visit Tokyowhere Id be for about four months, conducting research on a matsuri, or ritual festivalin about a months time.

My father didnt have much to say about this, so the conversation drifted into silence. While he and my mother were always supportive of my path in life, the intense connection Id always felt toward the culture and history of Japan slightly baffled them: it had become something of a family legend that as a child I would insist on dressing up as a miniature samurai before going to the corner shop to buy the milk and bread.

I promised to call my parents again before my departure. Then, just as I was hanging up, I heard my father give a nervous little cough. This was often a sign that something was troubling him. I hesitated, but before I could ask him if all was well he had put the phone back on the hook. Throughout our conversation hed given no other indication of the dramatic scenario that was forming in his mind.

My eyes fixed on the note again: OVER AT DAPHNES DAD . Although it had to be true, I still couldnt quite believe that my father was here, and I felt a rising unease. What was he doing here? Ever since Id been a student at Oxford Id wanted him and my mother to visit me. My mother had been keen to do so but had always been held back by my fathers reluctance: he hadnt been back to Europe since leaving in 1949 and was adamant that he didnt have the slightest interest in returning.