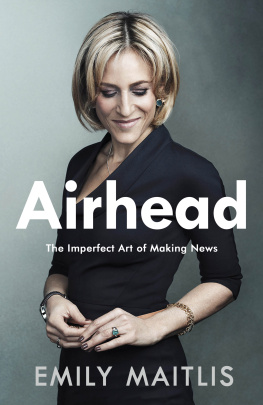

Emily Maitlis

AIRHEAD

The Imperfect Art of Making News

MICHAEL JOSEPH

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Michael Joseph is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

First published 2019

Copyright Emily Maitlis, 2019

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Cover image Stuart McClymont

ISBN: 978-1-405-93835-8

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorized distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

For my boys, Milo and Max, who have inspired me and laughed at me in equal measure.

And for Mark, who agreed to marry me, and who continues to make every day of my life better. It was the best question I ever asked.

The first and greatest sin of the deception of television is that it simplifies; it diminishes great, complex ideas, stretches of time; whole careers become reduced to a single snapshot.

James Reston Jr, Frost/Nixon

Introduction: The 2 a.m. Call

My phone is on silent. But its still managed to wake me up. The yellow flashing glare perhaps or a sort of fuzzing of atoms. Its 2 a.m. and I see on the screen its my Newsnight editor, Ian Katz.

No thanks, I think, and hide it under a book about psychological warfare. Its the heaviest one next to the bed.

Ian has a way of wanting to talk about things at odd hours. He normally catches up on his texts around one in the morning which is lovely for him, but slightly confusing for everyone else. This time, Im not in the mood. Its a Friday night in November 2015. I have just stepped off a plane from Washington, after two weeks on the road, reporting. My body doesnt know what continent Im in or what day it is. Ive had a vodka shot and a blue sleeping pill and, frankly, Im out for the count.

But five hours later, my phone is still ringing from the depths of psychological warfare where its been buried. And this time its my deputy editor, Rachel Jupp her voice sounds both apologetic and pleading. We need you to go to Paris.

I am still asleep, my eyes wont open, my mouth is gluey and stuck. But my mind has raced ahead to the sense of what shes saying, and from nowhere I hear myself weighing up her request, asking the worst question a journalist can ask:

How many?

And she tells me more than a hundred are dead many inside the Bataclan theatre and several gunmen are still on the loose.

Two hours later, Im on the Eurostar. My usual grab bag packed for emergency travel had just been emptied into the wash, so Ive scrabbled together just enough to see me through the next forty-eight hours. Something dignified for on-air reporting. Something warm for all the waiting around. Something waterproof for when the heavens open. A zillion chargers, adapters, cables and three slabs of dark chocolate for skipped-meal replenishment.

There is a familiarity to this journey. Just ten months earlier I had taken the same Eurostar to cover the Charlie Hebdo massacre. Subliminally, I have begun to associate the City of Light with darkness and fear. The Gare du Nord still makes me shake.

This time, scrolling through emails on the train, I find a generic BBC one sent to all those heading to Paris. It tells us to avoid a black licence-plate-free Renault if we see it. They believe its being used by the terrorists and is packed full of explosives. The email is meant to be helpful, but it makes me burst into tears. I havent seen my kids for two weeks, I havent slept more than a few hours in two days, I havent eaten since the plane, and now Im being told to avoid black cars. What am I even doing?

Paris isnt really working when I arrive: you cant get a cab, police barricades are up all over, the streets are eerily empty in parts and rammed full in other places where spontaneous virgils have sprung up. We broadcast for an hour a BBC Two Saturday-afternoon special from outside the Bataclan; we are asking people to give us eyewitness accounts of events they havent even processed. I find the band U2 leaving flowers beside our live point, their own commemoration of young lives lost in the simple act of attending a concert.

The terrorists have struck when Europe is already feeling fragile; the migrant crisis has brought thousands from the Middle East and Africa some seeking asylum, others better employment marching across the continent and making EU politicians assess their own political response to the outsider. That night, as we try and piece together the scale of the tragedy, all sorts of conflicting narratives begin to emerge: that the terrorists were home-grown, or Syrian, or from neighbouring Belgium. That they were ISIS fighting jihad in France, or they were disenfranchised young men betrayed by their treatment as Muslim French citizens. It is too early to know why its happened. We barely understand what has happened.

Over the weekend, we see the raw Gothic beauty of Notre-Dame reflected in the flickering of a hundred tiny candles of remembrance on the ground. In Place de la Rpublique, a shrine has evolved photos of loved ones, white roses, a lone violinist playing of the pain which has only started to seep into this grieving city. As I cross the square, a French reporter recognizes me and asks if we, the English, are sympathetic. It is such an extraordinary thing to ask I feel my eyes welling up again. Surely we are beyond the Hundred Years War, the neighbourly rivalry of World Cup penalties. I cant even find the words to tell him that yes, God knows, we are.

By Monday night we Newsnight are back on air. I have already fronted a Panorama report for BBC One and I have interviewed (in French) Rachida Dati, the former French Justice Minister with special focus on migration and counter-terrorism, who blames Angela Merkel for the error of judgement in letting so many people cross into Germany. Now I am standing in front of the camera, microphone on, facing one of the most complicated live shows we will ever attempt. We have seven live guests, three different reports, Gabriel Gatehouse will be live in Greece with those crossing the border and our investigations editor will be live in London with news of what theyve learnt. It is ambitious and complicated and we are about two minutes into the live forty-five-minute programme when everything starts to go wrong.

It goes wrong when I suddenly shout MIGRANTS! down the barrel of the camera, without realizing my microphone is faded up. The word comes as such a shock to our investigations editor he yanks his head up and his earpiece pops out. I am standing there looking like a swivel-eyed xenophobe stuck in the middle of Paris, but I am broadcasting to millions live on telly. And the reason I have just yelled Migrants! out loud, as if seeing a crowd of thousands descend on Place de la Rpublique, is because I am trying to warn my producer, Vara, which sequence is coming up next so she can ready the guests and bring them in. I have to be the conduit between the London studio and her as I am the only one who can hear the programme go out. I do not realize at this point my microphone has accidentally been left on. I do not realize my exclamation has come out of nowhere; I do not realize that in homes across the land viewers trying to piece together the horror, grief and pain that has left more than 130 dead in our neighbouring capital will simply see a deranged anchorwoman in the throes of verbal spasm.