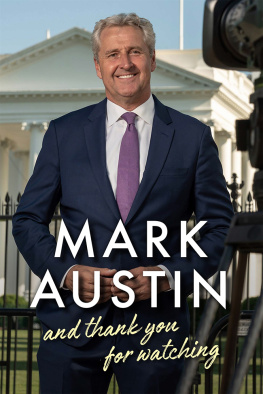

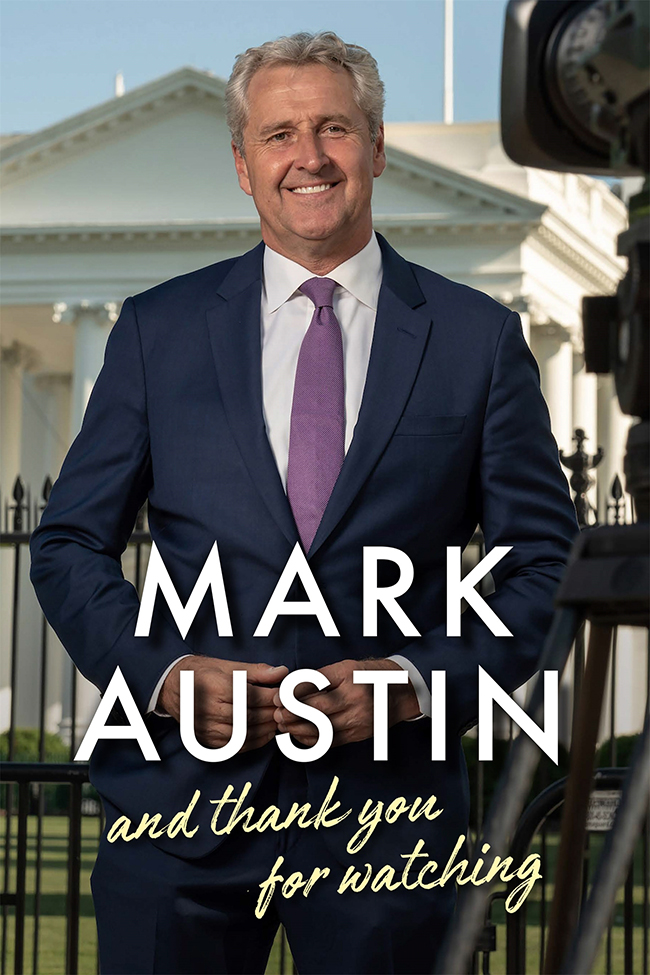

First published in hardback in Great Britain in 2018 by Atlantic Books,

an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright Mark Austin, 2018

The moral right of Mark Austin to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

The list of picture credits on p.337 constitute an extension

of this copyright page.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978-1-78649-449-8

E-book ISBN: 978-1-78649-451-1

Paperback ISBN: 978-1-78649-450-4

Printed in Great Britain.

Atlantic Books

An Imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

2627 Boswell Street

London WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

To my family, especially Maddy, who has been to hell and back, and then had the courage to help others.

And to Didier Drogba

19.05.2012

CONTENTS

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

INTRODUCTION

T HIS WAS NOT how it was meant to be. I had always wanted to play cricket for England or be a drummer in a rock n roll band. So what the hell was I doing standing on parched scrubland in the South African bush with a gun to my head?

I had been marched into the field at gunpoint, ordered to look straight ahead and say nothing. If I turned around they would shoot. My mouth was as dry as the terrain around us. The men were angry, very angry, and kept screaming at me. I couldnt understand a word they were saying. I was gripped with fear, felt nauseous and thought I was probably going to die. My young producer, standing alongside me, thought we were definitely going to die. He was shaking. It was his first major foreign assignment. And there we were, side by side, facing possible death at the hands of screaming Afrikaner militiamen. In Bophuthatswana, for Gods sake. A place no one had heard of. On a wretched story no one would remember in a few months time and, worse, would not matter in a few weeks time. What a way to go. Wrong place, wrong time again!

Or not, because the two most prized boasts of the foreign correspondent are I was there and, even better, I was there first. It is what we do. We go. We always go. It is not in most cases through any great bravery, or a warped desire to notch up a close scrape in a South African field. It is because we want to be there, we want to witness what is happening and we want to get the story out to the world.

So, wrong place, wrong time? No. In fact, in this business the opposite applies. It is the madness of what we TV news people do. What we choose to do. I was actually in the right place at the right time. It may have turned out to have been the wrong place had that gunman pulled the trigger. But I was where I wanted to be, and yes, where I had to be if I wanted to get the story.

I say this because, if you are reading a book about the life of a foreign correspondent and travelling anchorman, it helps, I guess, to understand what motivates us. It is sometimes glamorous, often exciting and frequently fascinating. But it also can be tedious, dispiriting and routine. And yet time and again we are drawn to places like Afghanistan, Bosnia, Iraq, Syria and Sierra Leone. It is part competitive urge, part a need to be there, and part the desire to seek out the truth or as close to it as it is possible to get.

I am not one of those war junkie correspondents who thrive on the adrenaline of conflict and witnessing bad stuff. I have known many reporters male and female who are in their element in war zones, who love the challenge, who relish the hardship and even find the danger quite alluring. I say this not in criticism; in fact, quite the opposite. I have undiluted admiration for the journalists who do feel that way. They are brave, courageous and resourceful. And the bottom line is this: if they did not go to the godawful places to bear witness, who would do it? Who would be there to cast a light on those dark corners of the world where conflict rages, war crimes are committed and atrocities take place? The answer: no one.

And that is just what those who perpetrate such monstrous outrages want to happen. They want to operate in obscurity, in darkness. Good war reporters dont allow that. They shine a light. The Anthony Loyds, Jeremy Bowens, Marie Colvins (God rest her soul), Christina Lambs, Kim Senguptas, and countless cameramen and women and photographers of this world should be saluted for the work they do.

However, I am not someone who welcomes the danger. I have been to many war zones, but I dont relish it, I dont feel some sort of missionary zeal to do it and I certainly dont enjoy it. The fact is, if youre daft enough to agree to go to these places, and you do it often enough, you will get into difficulties. More often than not the threat is sudden and comes from nowhere, and whether you live or die can be pure luck which road you take, which hilltop you film from, which hotel you stay in, which local fixer you hire, and who you take advice from.

I have good friends who have been killed or seriously injured in war zones. I was with the ITN reporter Terry Lloyd the night before he and his cameraman and their fixer were killed in Iraq. That story is in this book. The BBCs John Simpson, one of the great foreign correspondents of our age, was with his camera team in northern Iraq when they were bombed by friendly forces who got their coordinates wrong. He survived. Terry didnt. The lottery of war.

I survived, or at least I have so far, largely due to an innate cowardice. In fact, Ive found that cowardice is a much better protection than any amount of flak jackets, helmets and armoured vehicles. Cowardice has stopped me going to many places and doing many things in war zones, and I think there are many camera crews and producers who would probably thank me for that. My cowardice has served me well.

This book is not supposed to be just about war stories or close brushes with death. I have included them because that is what I get asked about most often, but also because most intensely insecure TV reporters, particularly those who later sneak off to the comfort and sanctuary of the studio to become presenters, like it to be known that they have earned their spurs, they have seen action and theyve been in the thick of it. I guess its the feeling that you havent made it until youve been shot at. It really is that pathetic. Honestly.

But this book is also about the other big stories I have been privileged to cover in thirty years as a foreign correspondent and presenter for ITN, and now as Washington correspondent for Sky News.

I write about the Rwandan genocide in 1994 and what its like to report on a story where almost a million people died at the hands of machete-wielding, grenade-throwing murderers, just because of their ethnicity. Recent African history is replete with outbursts of tribal slaughter, but this was a massacre on an altogether different scale. It was not a simple tale of mutual hatred between rival ethnic groups descending into terrible violence. This was a carefully planned, meticulously carried-out genocide. Genocide is an oft-misused word. Not in this context, though. A green, lush, beautiful land of rolling hills and endless valleys became a vast human abattoir. It is by far and away the most grotesque story I have ever covered. I have yet to meet a journalist who was not deeply affected by what they witnessed there. My friend, the BBC correspondent Fergal Keane, to this day has nightmares about being at the bottom of a pile of rotting corpses that are moving and touching him, like a mound of eels at the supermarket.