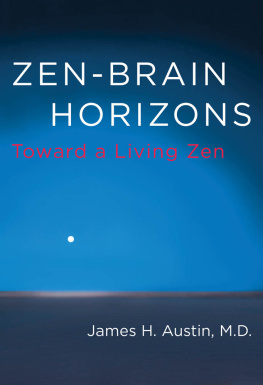

Zen-Brain Horizons

Zen-Brain Horizons

Toward a Living Zen

Austin, James H., M.D.

The MIT Press

Cambridge, Massachusetts

London, England

Also by James H. Austin

Meditating Selflessly (2011)

Selfless Insight (2009)

Zen-Brain Reflections (2006)

Chase, Chance, and Creativity (2003)

Zen and the Brain (1998)

2014 Massachusetts Institute of Technology

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Austin, James H., 1925 author.

Zen-brain horizons : toward a living zen / James H. Austin, M.D.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-262-02756-4 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Zen Buddhism. 2. BrainReligious aspects. 3. Cognitive neuroscience. I. Title.

ISBN 978-0-262-32116-7 (retail e-book)

BQ9288.A966 2014

294.3'927019dc23

2013046636

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To my early teachers Nanrei Kobori-Roshi, Myokyo-ni, and Robert Aitken-Roshi for their inspiration; and to all those whose countless contributions to Zen, to Buddhism, and to the brain sciences are reviewed in these pages.

Where the brain is abnormally moist, of necessity it moves.

And when it moves neither sight nor hearing are still. Instead, first we hear one thing and now another, and the tongue speaks incessantly in accord with the things seen and heard.

But when the brain is still, one can think properly.

Hippocrates (ca. 460377 B.C.E.)

List of Illustrations

Figures in black and white

Figure 2.1 Major anatomical landmarks on the left side of the brain14

Figure 2.2 Lateral view of the right hemisphere showing the dorsal and ventral attention systems15

Figure 3.1 Inside surface of the right side of the brain, showing the medial origins of the psychic Self as remote from the allocentric processing stream27

Figure 4.1 Leaf from a Bodhi tree (Ficus religiosa)39

Figure 11.1 Egocentric and allocentric attentive processing, illustrating major differences in their efficiencies100

Color plates following page 122

Plate 1 Egocentric and allocentric attentive processing, illustrating major differences in their efficiencies (discussed in chapter 11)

Plate 2 Lateralization of the color field to the left (discussed in chapter 12)

Plate 3 Coalescence of green into the left upper quadrant (discussed in chapter 12)

Plate 4 Midline circular zone of pink-purple (discussed in chapter 12)

Plate 5 Coalescence of pink-purple into the left upper quadrant (discussed in chapter 12)

Table 1 Measuring Happiness (chapter 15)172

Preface

It ought not to be inferred that living by Zen has something unique

or extraordinary about it, for it is, on the contrary, a most ordinary

thing, not at all differentiated from the rest of the world.

Daisetz T. Suzuki (18701966)

The skyline is a promise, not a bound.

John Masefield (18781967)

Living by Zen includes an awareness coextensive with all the rest of the ordinary, incredible world. So coextensive and so ordinary is Zen that it often regards itself as nothing special. Indeed, wherever we gaze in Zen we find that its unbounded horizon becomes universal in scope. Turning to look far back at meditations historical roots, we glimpse an approach that began millennia ago in ancient Yogic practices, then became increasingly institutionalized as it emerged through the cultures of East Asia. When the old Sanskrit term for meditation (dhyana) entered China, it changed there to Chan. When this Chan practice of meditation came to Japan, the word was pronounced Zen.

When we in the West now look back at this rich historical legacy, we discover contributions made by countless worthy ancestors. Why do these pages include so many of their words of wisdom? Because these pioneers seem almost to have anticipated research out on the near horizon of the neurosciences. In this sense, they were already pointing toward a living, neural Zen.

Two worlds meet along this horizon line. Below is firm ground, the earth on which we stand. It beckons us to explore tangible objects just out of reach, waiting to be touched and used. Extending far above the skyline is the infinite vault of the sky. Themes in this book often encourage us to raise our sights in this direction. These skyward dimensions invite us to glimpse loftier aspirations, to explore intangible frontiers where elevated potentials are not yet clearly defined.

Suppose we happen to rise very early, then go outdoors and gaze up above the horizon. Only by looking off to the east will we glimpse the first colors of the approaching dawn. Up there, when we see the bright planet Venus, what will be going on in our brain? Before a single thought enters, two attentive systems will already have taken the lead, blending into one unified image the distance functions of the right and left halves of our visual fields. We need to remind ourselves that this attentiveness plays an automatic vanguard role in all of our brains subsequent mental processing. Why do these pages emphasize the involuntary nature of such attentive processing? Because these covert functions, acting silently, make crucial contributions to all implicit learning, to intuition, and to creative insights of various kinds.

To D. T. Suzuki, who brought Zen to the West, living by Zen was a highly practical matter. To live Zen meant to be intimately attuned to the ordinary events in ones everyday world. Living Zen wasnt just sitting quietly indoors on a cushion. In keeping with Suzukis often expressed views about the Japanese love of Nature, and how this deep appreciation entered into the Zen cultural aesthetic, and Buddhist Botany invite readers to celebrate Earth Day every day, not only once a year.

Other chapters begin by looking far back into the remote past for an historical perspective on research that might appear out on some future horizon. The word horizon has an interesting history.

So, part I begins by looking far back into ancient historical narratives in preparation for the next leaps well then take into the neural perspectives of this twenty-first century.

Part II reviews themes that evolved during subsequent centuries when Zen and psychology each developed after having been exposed to different cultures.

Part III considers more recent information about how our brain changes when attitudes expand in the background of an increasingly clear, calm awareness.

Part IV explores the fresh perspectives inherent in those dimensions of visual space above our usual eye-level, limited horizon. We have yet to realize the full promise of these dimensions.

In part V we peer further out into the future. Among the topics considered, four themes are of universal human importance. They are creativity, happiness, openness, and selflessness.

Consider this book an invitation to discover in this new millennium the extraordinary promise inherent in seemingly ordinary things.

To sharpen the discussion, short statements or questions are inserted throughout, marked by bullets (). For the readers convenience, bracketed references in the text [ ] indicate pages in four earlier books that provide background information on the topics being discussed. For example, [ZB] refers to Zen and the Brain, [ZBR] refers to Zen-Brain Reflections, [SI] to Selfless Insight, and [MS] to Meditating Selflessly.

Acknowledgments

I am indebted to Philip Laughlin at MIT Press for appreciating the need to bring this slender volume to the attention of the wider meditating and neuroscience communities. Again, my sincere thanks go to Katherine Arnoldi Almeida for her skilled editorial assistance and to Yasuyo Iguchi for her artistic skill in designing the cover and icons.

Next page