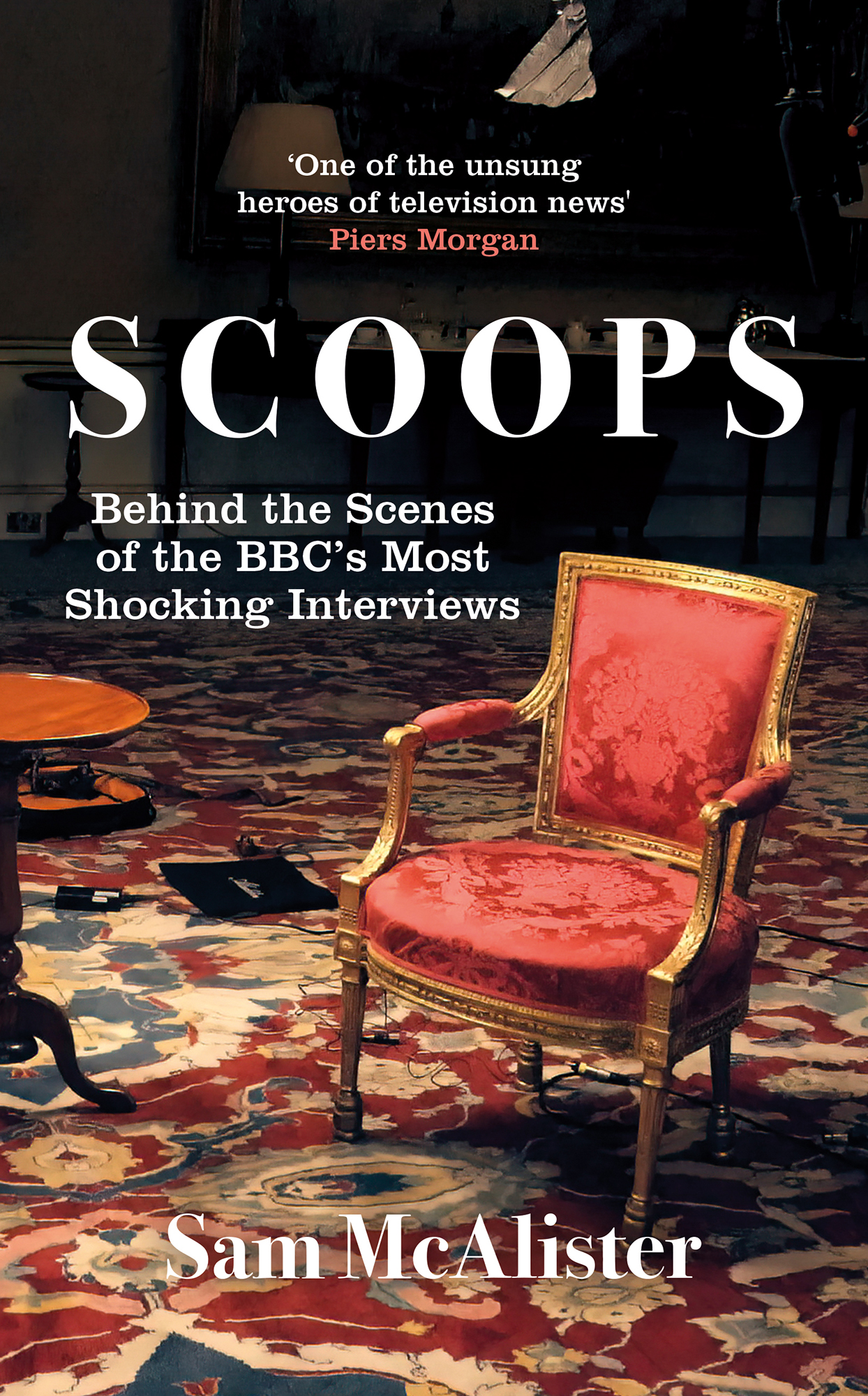

To my beautiful, clever, charismatic and resilient mum, Netta, who taught me to mix with princes and paupers, but probably didnt mean it literally.

And to Lucas, the best kid in the world.

Contents

Introduction

Relentless. Ive heard this word a lot. Its a moniker of admiration, confusion, and sometimes of abuse or ridicule. And it perfectly sums up who I am and what I do.

Im not sure when or how it started but I live to get the story, to beat the worlds media, to go first and, preferably, exclusively. News takes many forms and I dont discriminate Ive tracked down world leaders for their first interviews on the job, those on the brink of reputational ruin, and people who have everything, maybe even their life, to lose. Over the years, the desire to win has only grown. It has crept into every dinner, every party, every new acquaintance, every relationship, every business meeting. Every single encounter would allow me to build a crucial network to get myself into a position where I, someone who arrived in journalism with no connections, no credentials and, dare I say, no credibility, could access virtually anyone in the world.

My path to news addiction wasnt a traditional one. News and politics werent a feature of my childhood. In fact, they barely figured at all. We lived an itinerant life. My dad, who had made some money selling mobile homes, left the UK in the 1970s, moving my mum and me from tax haven to tax haven. Not the glamorous kind, like Monaco or the British Virgin Islands. Instead, he relocated us from the outskirts of London to Guernsey (so small I often felt I might fall off) and then to the Isle of Man (a cruel fate for any teen) and, finally, a short sojourn in Andorra (a flat perched in the mountains of a ski resort for three people who had never skied). These places shared something else in common they didnt see themselves as part of their parent countries.

Each small island or municipality had a certain autonomy over several aspects of its political, fiscal and social affairs and so you would have a feeling of belonging to something quite separate, figuratively and literally, from the larger powers just a few miles away. Usually, and quite understandably, the locals would, at best, tolerate or, at worst, actively detest the tax tourists who populated their small slice of the planet, filling their natural beauty with oversized cars and fragile egos. Of course, I knew I was British, but my concerns were with small island life. People were much more likely to be discussing matters that affected them close to home the cost of living, local services, neighbourhood gossip than the kind of big social and political issues that came to fill my later years. I knew there was a bigger world out there, but it felt entirely irrelevant to my existence. We left our cars and houses unlocked, children could amble to school alone, no one had ever been murdered, no one had ever been raped, there were no burglaries. Shoplifting and traffic infractions were about as thrilling as it got. Occasionally a sheep might mosey into the garden looking for excitement or, more likely, some fresh grass. Days merged into years easily and without incident. It was a time without pandemics, without terror attacks, without war. I rode my bike, climbed rocks, swam and revelled in the pleasures that island life can bring.

There was no pressure to achieve in the traditional way that so many middle-class kids seem to feel. My parents only expected me home on time and to be well mannered. My mum, a charismatic and beautiful woman, full of backbone and charm, had to leave school to earn some money. Her childhood was spent in the basement of what could only be described as a slum, a council flat in Stoke Newington, living hand to mouth with her brother, parents and a family of mice. Her childhood was Second World War London rationing, bomb attacks, nights spent in the underground, evacuation, a joyous return, and then more poverty and hard work than any child should have to endure. But nothing could stop my mum. The only thing she would tell me was that money comes and goes, so make sure you have the character to face the world. She told me that I should mix with princes and paupers, and treat them both the same. A lesson I carried with me all the way to Buckingham Palace.

She met my dad, whod left school to build and sell rabbit hutches, then caravans, during the Six-Day War in 1967. He stumbled upon her at the reception of a London hotel they were both staying in, as she was loudly berating the manager who had just refused to let two gay men check in. He instantly decided that this woman was for him. They soon moved in together, she started selling caravans too, and they settled into their pattern of seven-day work weeks, no rest, no holidays, no respite. Both my parents loved to work. And so my genes were firmly entrepreneur and sales based, as they sold caravan after caravan, and moved from slums to flats to houses, from market stalls and small towns to running businesses and holidays in Monte Carlo, from council flats to houses with a swimming pool. They were social mobility personified.

And so I entered the mix of fun and hard work, whereupon my folks decided to pack it all in and move from Surrey to Guernsey. I cant even imagine what a culture shock it was for my poor mum who went from glamour, independence and full-time employment to island life, surrounded by women who didnt work, many of whom disliked her confidence. And for my dad, who went from workaholic to full-time retiree, at the age of fifty-one. What seemed like an amazing opportunity to retire young and enjoy life quickly descended into a mundane existence, a man who was no longer king of his domain, and instead at the behest of a new life, a new baby, and a community without the dynamism he had once enjoyed. He was also a manic depressive. Back before anyone really knew what to call it. And so, my mum was stuck on a new island, with a new baby, no friends, no family, no job, and with a partner who spiralled between elation and depression.

My parents were delighted that I showed academic promise and supported me in every conceivable way but my childhood was the Daily Mail , the Express , Coronation Street and Jackie Collins. It was a very different upbringing to that of so many of my colleagues in later life. I was tabloid to their broadsheet, panto to their opera, Jilly Cooper (what a legend) to their Jane Austen. I didnt live in a world in which intellect, status and worth were measured by your understanding of politics, or history, or whether you could speak Latin.

By the time I was doing my A-levels, it was clear that I was going to university. This was a huge deal for my parents who had never had that chance. We had no idea how to apply or what you do. We were oblivious to the rivalries between certain places, that you cant apply for this one if you apply for that one, or even the massive impact that me deciding that Oxford and Cambridge were too snooty could have on my future success. And so, my mum and I packed up and decided to visit all the places I liked the look of. We had baked potatoes in Norwich, a tour of the sights in York, and a very persuasive coach trip from the airport in Edinburgh. I dont know how most people decide where to go, but I can confirm that sharing an airport bus full of rugby players from Edinburgh Uni was pretty much 99% of my motivation for choosing to go there. It was a good starter city for someone who had always lived in the relative calm of island life. The culture shock was less stark than it would have been if Id gone to LSE (not that I knew that at the time).