Table of Contents

For Davis

Acknowledgments

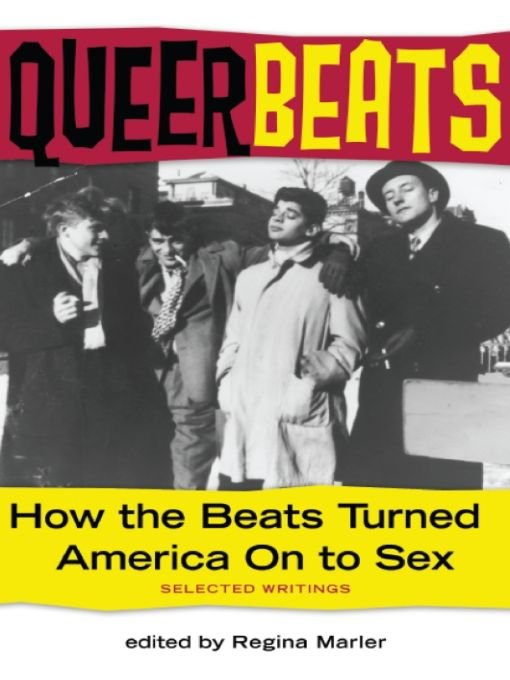

I would like to thank Don Weise for suggesting this book to me, and Ruth Davis, wherever you are, for giving me a paperback copy of On the Road as an entree to adulthood. To my publishers, Felice Newman and Frdrique Delacoste, thank you for your patience and good humor.

I am grateful to the following angels for offering information, guidance, support, and tender, loving care in the writing of Queer Beats: Peter Hale of the Ginsberg Trust; James Grauerholz of the William Burroughs estate; John Giorno; Harold Norse; Brenda Knight; Allen Young; M. DuBose; Ira Silverberg; Leo Skir; Holly Bemiss; Randy Wicker; Jack Nichols; Gina Allison; Renee Marler; and Paul Yamasaki of City Lights Bookstore. Im sure this list is incomplete. If Ive omitted any names here, it is unintentional.

This book would not be possible without the amazing critical and textual efforts of the scholars and writers who have preceded me in this rich field. I could not begin to name all the works I have drawn on in my study of the Beats, but I can say that my understanding of Burroughs was shaped by Oliver Harriss edition of his letters and by Jamie Russells remarkable Queer Burroughs, that Ann Charters Portable Beat Reader was my frequent companion, and that my sense of Ginsberg was guided by the twin lights of Barry Miless definitive biography and Jane Kramers skillful, devilish portrait, Allen Ginsberg in America. Anyone hoping to understand the Beats in the context of the 1950s would do well to begin with John DEmilios Sexual Politics, Sexual Communities, Diane di Primas Recollections of My Life as a Woman, and Brenda Knights Women of the Beat Generation.

Sooner murder an infant in its cradle than nurse unacted desires.

WILLIAM BLAKE

Did I tell you about the rat who was conditioned to be queer by the shock and cold water treatment every time he makes a move at a female? He says: Mine is the love that dare not squeak its name.

WILLIAM BURROUGHS

Introduction

I n the summer of 1948, Allen Ginsberg sublet a Spanish Harlem apartment from a fellow student at Columbia University and began reading the theology books stacked around the room in orange crates. In a mystical frame of mind, he pored over William Blake, Saint Teresa of Avila, Saint John of the Cross. One afternoon, he lay on the bed by the open window, his pants unzipped, reading Blakes Ah! Sunflower while masturbating. After he came, he heard a low, ancient voice that seemed to emanate from somewhere in the room. It was the voice of Blake himself, he realized, reciting his own poem. The peculiar quality of the voice was something unforgettable, Ginsberg later explained, because it was like God had a human voice, with all the infinite tenderness and mortal gravity of a living Creator speaking to his son. The vision persisted, accompanied by heightened visual perception and a sudden knowledge of the wondrous complexity of nature and the divine significance of the works of man: I had the impression of the entire universe as poetry filled with light and intelligence and communication and signals.

The dead poet read other verses from Songs of Innocence and Songs of Experience, in each of which Ginsberg now saw himself as the subject. He was the rose in The Sick Rose and Lyca, the girl, in The Little Girl Lost. As the vision faded, he stumbled, ecstatic, onto the fire escape and shouted into the neighboring apartment, Ive seen God! The two girls inside slammed the window shut. Later, his psychoanalyst hung up on him. He told his father, too, who worried that Ginsberg was showing signs of the schizophrenia that had caused his mother to be hospitalized.

For the next fifteen years, Ginsberg would try to re-create this rapturous experience through the use of drugs of every kind, even journeying alone to the jungles of Peru in search of a hallucinogen called yage, used by witch doctors. The Blake vision was so pivotal for Ginsberg that several versions of the story exist, in all of which his pants are open but in none of which does Ginsberg or his interviewer think to remark on this. The masturbation is an integral part of the scene; including it is as natural, for Ginsberg, as describing the brilliant blue of the sky outside the apartment window. So effectively did he project in his writings his sense of these transporting moments and their lasting significanceand so powerfully did his sensibility alter the world around himthat by the time he gave the 1966 Paris Review interview from which Ive drawn these quotes, his open fly was a mundane detail. Hed helped create a culture in which references to a hand on a cock can go without notice.

This candid attitude toward sex and the bodytoward pleasure in generalis one of the enduring legacies of the Beat writers, though only Ginsberg would fulfill this ideal to the extent of appearing naked at parties full of clothed people. Theirs was a revolution of flesh as well as the word. The orgies, addictions, and all-night Benzedrine-fueled writing binges of Beat legend are, in the end, inseparable from their search for the ultimate reality of the kind embodied in the Blake vision or in the high-speed, cross-country road trips immortalized in Jack Kerouacs On the Road.

Those who read beyond the legend know that Kerouac retreated to a paranoid conservatism in his forties, that the openly gay Ginsberg, even in midlife, often longed for a wife and children, and that William Burroughs would sometimes, when kicking a drug addiction, claim that he wanted cunt, that he was never meant to be queer. These are the contradictions of actual lives, of midcentury lives in particular. The Beat writers did not always bring these conflicts into their works, though they aired them in conversation and letters. This open confession of their feelings was one of the pivots of the movement, and no less vital to their influence on the rising counterculture than their marijuana reveries and restless experiments in literary form.

The groups origins lay in friendships formed at and around Columbia, in upper Manhattan, in the months after Christmas 1943, when Allen Ginsberg, then a freshman, met a raffish, angelic-looking aesthete named Lucien Carr. It was the sophisticated Carr who first took Ginsberg down to Greenwich Village to meet queer and interesting people, as Ginsberg wrote to his brother Eugene, adding that he planned to try to get drunk. Soon after this walk on the wild side, Carr introduced him to Jack Kerouac, an ex-Columbia football player and aspiring writer, and Dave Kammerer, an older gay man whose life was organized around a hopeless love for Carr that dated from Carrs childhood in Saint Louis. At Kammerers place, they met another exile from Saint Louis: William Burroughs, a thirty-year-old Harvard graduate and escapee from respectability whose friends included petty thieves, hipsters, junkies, and Times Square hustlers, like Herbert Huncke, as well as a number of pretty boys, immortalized in Kerouacs Visions of Cody as the Sensualists. Along with higher-minded works like the philosophy of Spengler, the novels of Genet were among the first books Burroughs passed on to his younger friends. He led them around Times SquareKerouac in terrorin and out of gay bars. Burroughs made no secret of his orientationhe had cut off the tip of a finger to impress one piece of tradebut Ginsberg was still unsure of his. A virgin with both men and women, he had fallen in love with the golden-haired and irredeemably straight Lucien Carr, and then with Kerouac, too. The friends indulged in marathon, late-night arguments in cafeterias, drank hard, discovered drugs. Kerouac, who had lost his best friend in the war that spring, was hungry for intensity, for purity. In his own blood, he copied out a Nietzsche quotation: Art is the highest task and the proper metaphysical activity of this life.