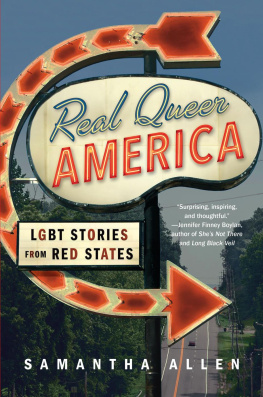

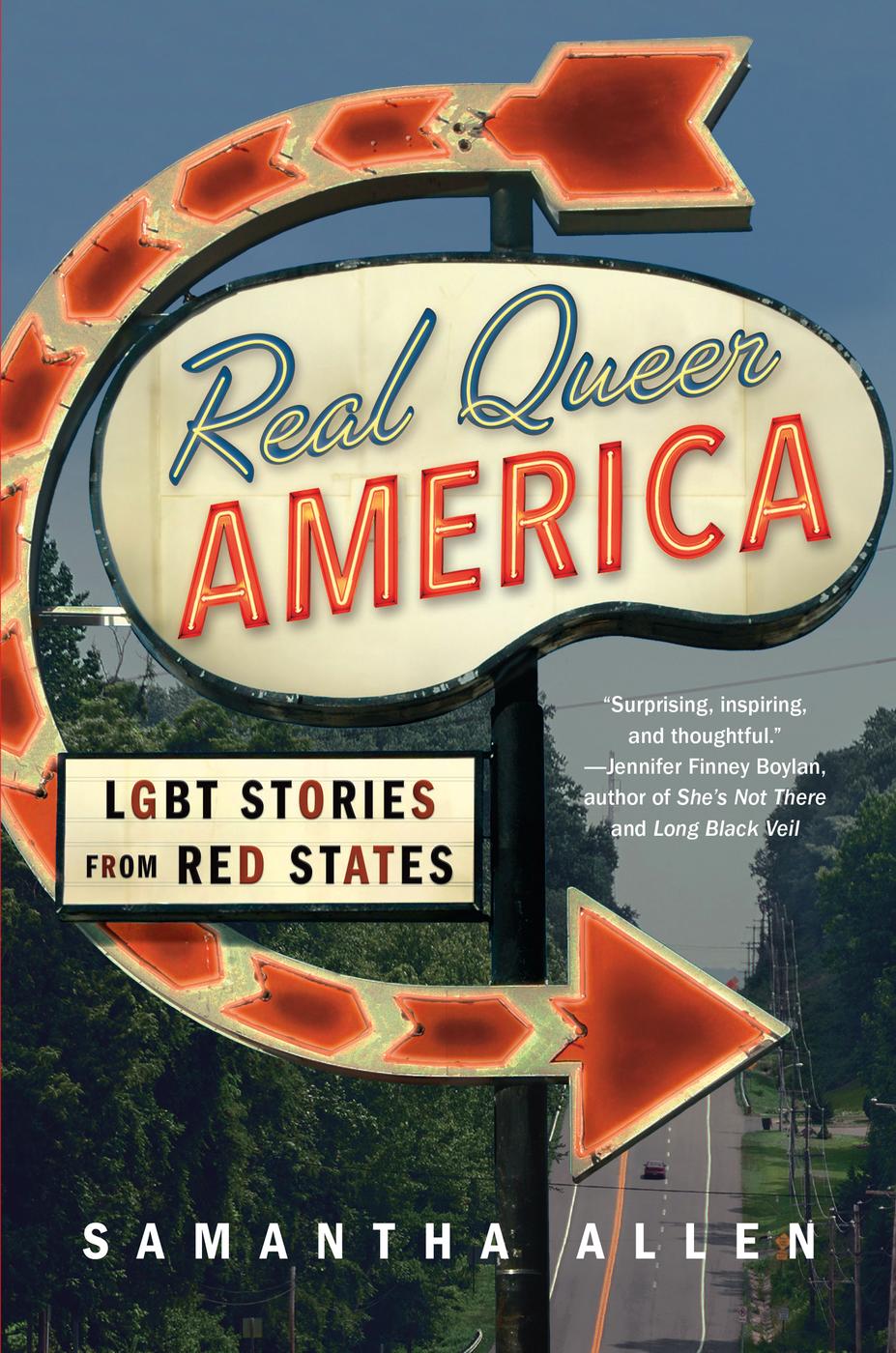

Copyright 2019 by Samantha Allen

Cover design by Lucy Kim

Cover photographs: sign Darla Hallmark / Shutterstock; road franckreporter / Getty Images

Author photograph by Corey Burke

Cover 2019 Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Little, Brown and Company

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

littlebrown.com

First ebook edition: March 2019

Little, Brown and Company is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Little, Brown name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

Portions of the introduction appeared in the Daily Beast in 2017. Used with permission of The Daily Beast Company LLC.

ISBN 978-0-3165-1601-3

LCCN 2018949002

E3-20190205-DA-NF-ORI

For my parents, Nina and Gil, and my passenger, Corey

Harry, I have no idea where this will lead us, but I have a definite feeling it will be a place both wonderful and strange.

Federal Bureau of Investigation Special Agent Dale Cooper

I was reborn in a car.

It was a silver 2005 Honda Accord SE with seat warmers, a six-CD stereo, and delightfully slippery black leather seats. When driven by a jobless college student like me in the year 2007, it practically screamed, This belongs to my dad!and it did. But that year, it was mine.

By appearances, I was one of thousands of young men studying at Brigham Young University, school of choice for the Mormon faithful. But most nights found me cruising around the eerily neat grid of Provo, Utah, in that hand-me-down sedan, searching the citys plentiful parking lots for isolated corners where I could apply makeup and change into womens clothing unseen.

My nocturnal transformations werent pretty. I smeared my eyeliner. I confused tube tops for skirts and vice versa. But the awkward, liminal creature I saw in the visor mirror was meor at least a shadow of me, a precursor of the woman I would one day become.

That possibility was still unimaginable to me in 2007. Coming out as a transgender woman didnt feel like a real option then; my enrollment at BYU and my full-ride scholarship both depended on my obedience to the schools strict anti-LGBT honor code, which forbade cross-dressing and homosexual conduct. Mom and Dad, I safely presumed, would not be thrilled if the son they financially supported dropped out of college to become their daughter. But the veneer of male heterosexuality that I was putting on for BYUand for my Mormon girlfriend at the timewas growing less convincing every day.

I tried to tell myself that I was happy being just a cross-dresserthat transition was not my eventual goalbut even I didnt believe me.

I was honest with myself only in that car. Shielded from the conservative college town by just a few inches of glass and steel, I felt like I could reach out and brush my fingers against the barest outline of a female future. Two thousand miles of Route 80 lay between my devout Mormon parents and myself. My clean-cut roommates either had no idea where I went after midnight with an overstuffed backpack slung over my shoulder, or they didnt care.

So I changed. And I drove.

I drove north past the Mormon Temple that looks like a gleaming white birthday cake with a single candle, past the mall on U.S. Route 189 where I saw my first R-rated movie in a theater, and then up the canyon highway where there were no more stoplights to slow me down. I hurtled up that canyon road until the lights of the valley were below me and the stars stood out against the jagged swath of night sky between silhouetted peaks on either side. When morning came I would be back in khakis, bowing my head in prayer at the start of my first class. The dreary Mormon ruse would begin anew. But as long as my foot stayed on that pedal, I felt alive. Thats how I started the messy process of becoming Samanthaand thats how I fell in love with the road.

The reassuring hum of an engine, the thrill of a blurry world whooshing past your windshieldthese are seductive enough forces in their own right. When they provide the only momentum in a life that feels stalled, they become irresistible.

Im still driving todaynow with a passenger. Years of hormones and surgeries later, the outline of that once-impossible future has been filled in, the M on my birth certificate erased and replaced with a reaffirming F. I officially resigned from the Mormon Church in 2008, dealt with the resulting familial drama, and came out as a transgender woman four years later. Most important, I got married to another woman in 2016a woman named Corey who not only accepted me but who guided me through the early stages of gender transition. With her help, I can finallykind ofdo my eyeliner.

Much of my painful past is now in the rearview mirror, and my car long ago stopped being the only place where I felt free, but I have never stopped roaming. That need to feel the asphalt under my wheels, to count the mile markers as they whiz by, to track down the best-lit gas station on a dark highway at 2 a.m.that hasnt gone away. Cars, for me, are still places of refuge, portals to distant possibilities.

I have crisscrossed the United States half a dozen times and counting. I came out as transgender in Atlanta, Georgia; fell in love in Bloomington, Indiana; and found my ride-or-die friends in East Tennessee. This is what Ive learned on my travels: America is a deeply queer countrynot just the liberal bastions and enclaves, but the so-called real America sandwiched between the coasts. I was once terrified to be transgender in Utah and queer in Georgia. Not anymore. I love this damn country too much to write off the majority of its surface area.

Thats why I wrote this book. Real Queer America is the product of a six-week-long cross-country road trip through LGBT communities in red states. It is, for me, a direct continuation of those late-night drives up Provo Canyon. Call it a spiritual successor. I will take you along with me on a trans-America trek: a journey stretching all the way from Provo, Utah, to the Rio Grande Valley, from the Midwest to the Deep South, meeting and interviewing extraordinary LGBT people along the way.

When I told friends and family I was writing this book, their immediate response was usually one of concern: Be careful. I get it. This might seem like a frightening time to be queer in the U.S.A., let alone for a transgender reporter to cross its most conservative regions by car. Many of the states on my itinerary had draconian anti-LGBT laws on the books at the time of my tripand many still do. Some had even more pernicious bills waiting in the wings.

With President Donald Trump in the White House, too, the federal government was stacked with figures who posed an unprecedented threat to LGBT rights: our right to work, our right to marry, even our right to use the bathroomand theres no way to get from coast to coast without having to pee in half a dozen different states.