ALSO BY DAVID M c GLYNN

A Door in the Ocean

The End of the Straight and Narrow

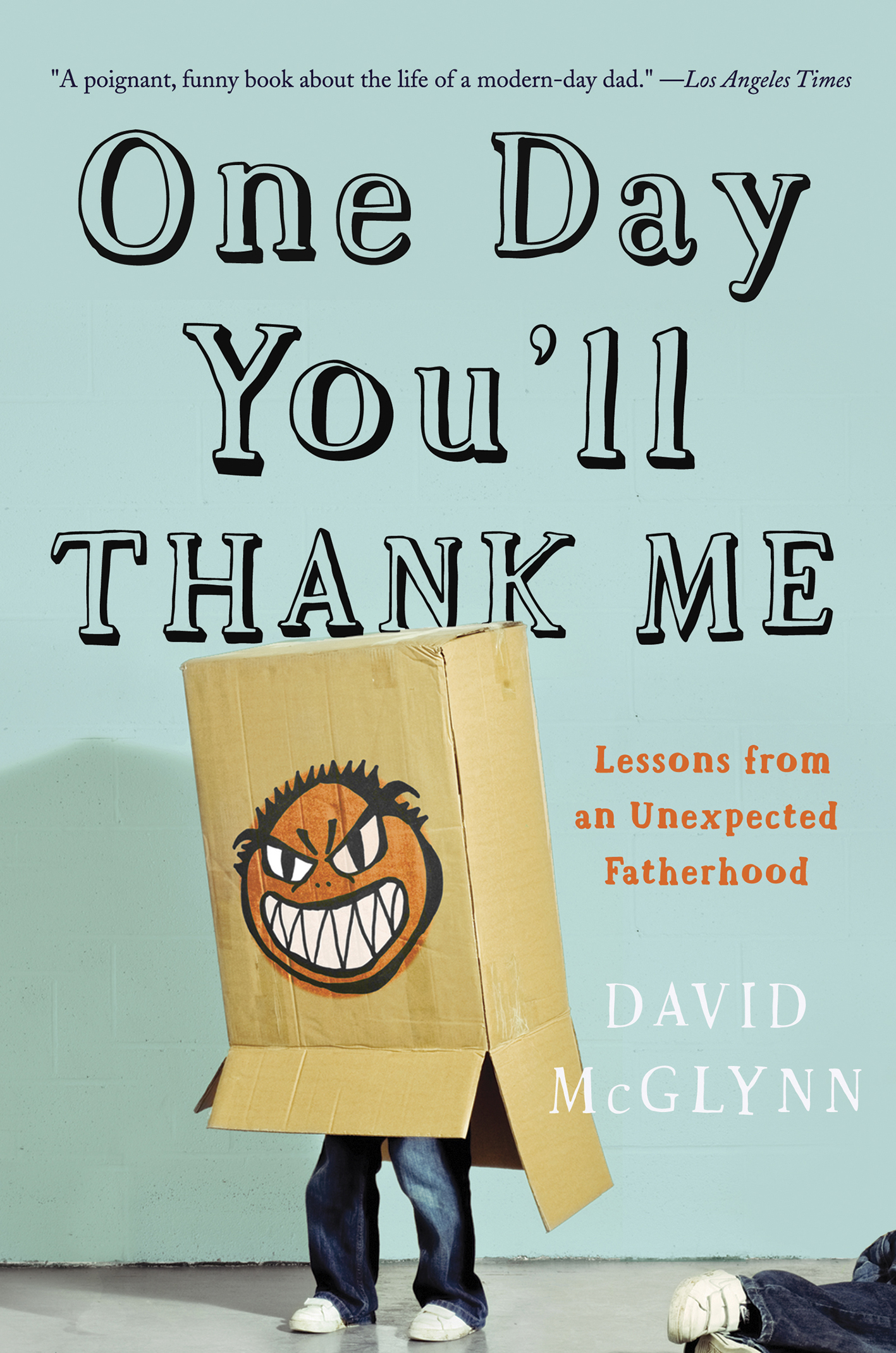

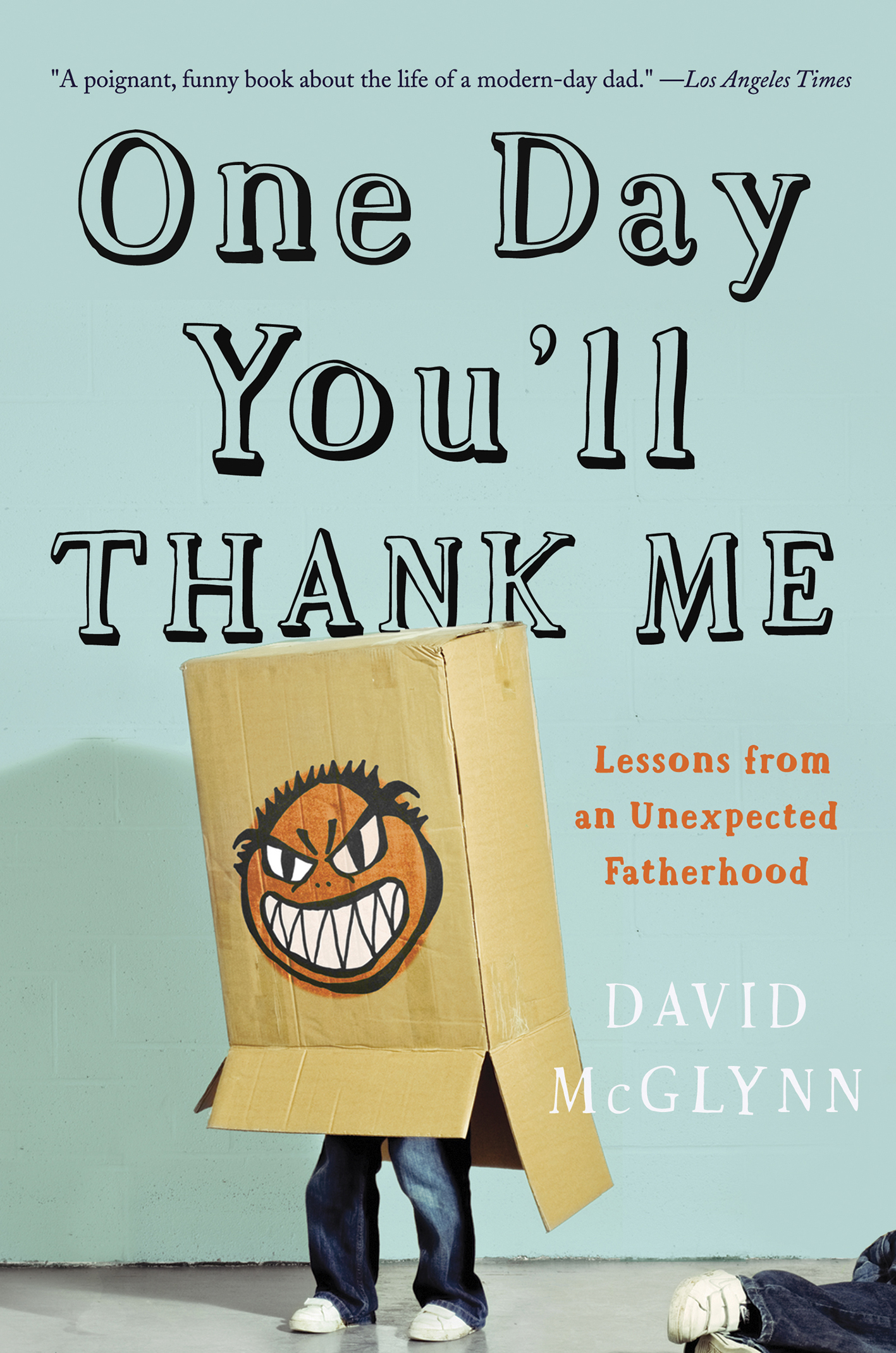

One Day Youll Thank Me

Copyright 2018 by David McGlynn

First hardcover edition: 2018

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: McGlynn, David, 1976 author.

Title: One day youll thank me : lessons from an unexpected fatherhood / David McGlynn.

Description: Berkeley, CA : Counterpoint Press, [2018]

Identifiers: LCCN 2017052590 | ISBN 9781640090392 (alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: McGlynn, David, 1976Family. | Authors, American Biography. | FatherhoodAnecdotes. | Father and childAnecdotes. | FatherhoodHumor. | Father and childHumor.

Classification: LCC HQ756 .M3866 2018 | DDC 306.874/2dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017052590

Jacket designed by Nicole Caputo

Book designed by Jordan Koluch

COUNTERPOINT

2560 Ninth Street, Suite 318

Berkeley, CA 94710

www.counterpointpress.com

Printed in the United States of America

Distributed by Publishers Group West

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Pop, Little Self, and Hugs

A father is a man who fails every day.

MICHAEL CHABON

Contents

Daddy Did It

T he night before he left Texas, my dad took my sister and me to dinner at a restaurant with a name I always liked: Daddy Did It Fish House. The name seems ironic now, but it didnt then. I was twelve years old, and Id been to oodles of restaurants in the year since my parents had separated: Whataburger and Two Pesos and questionably hygienic oyster bars down near the Ship Channel where the half shells were served on beds of slimy green ice. In other words, all the places my mother never wanted to go. She didnt like Daddy Did It, either, because she thought the name was stupid and catfish and hush puppies were redneck foods. Compared to most of the places we went that year, Daddy Did It was the Ritz, with chairs that werent bolted to the floor and utensils that didnt come wrapped in cellophane.

Dad had rented a spare room in a friends apartment on Lower Westheimer, near the Galleria, in central Houston. He slept in a sleeping bag on a bare mattress on the floor. Everything he owned was still at our house, including most of his clothes. When we visited, Devin, four years younger than me, tucked in beside him on the mattress and I slept on the couch in the living room. Hed talked for years about getting out of Texas and living closer to the beach. Now Dads things were in a moving truck, and tomorrow he and my soon-to-be stepmother were lighting out for Southern California.

At dinner Dad showed us grainy Polaroids of his new apartment and gave Devin and me, as going-away presents, boxes of cards already stamped and addressed to him. I recognized my stepmothers elegant cursive and tried to connect her handwriting and the address on the envelope to my fathers name. All you have to do is write inside it, fold it up, and drop it in the mailbox, Dad said. Well be pen pals. The idea seemed such a perverse reduction in status, from parent to pen pal, that he immediately took it back. You can call me anytime you want, he added. That promise made us all feel a little better. The waitress brought out the food and refilled our water glasses. When our plates were clean, Dad gave us each a handful of pennies to toss in the giant washtub at the front of the restaurant while he settled the bill. Devin closed her eyes and wished upon every coin. I tried to bean the oversized goldfish trolling along the bottom of the barrel. The fish darted from each penny I threw.

The divorce stipulated that my sister and I would spend four weeks a year in California. A week at either Thanksgiving or Christmas, and three weeks in August. I thought of our first trip to see him, for Thanksgiving, as an adventure. Dad had only been gone for three weeks, not long enough for me to miss him. His apartment wasnt much larger than his old one, only two bedrooms, the second one occupied by my stepsister, Stacie. Devin slept on the trundle mattress that slid beneath Stacies bed while I once again sacked out on the living room couch. I didnt mind; there was comfort in the familiar, even if the couch was rattan and creaked beneath me every time I shifted my weight. The balcony off the kitchen overlooked the swimming pool in the complexs courtyard as well as, if you moved to the left, the parking lot of the supermarket, where each morning at three oclock a garbage truck emptied the Dumpsters. The dining room wall and the floor behind the love seat towered with moving boxes full of my stepmothers mysterious possessions. Very few things had come from our house in Texas, and this apartment, like the place in the Galleria, felt temporary, as though Dad were on an extended business trip. Before moving, hed talked up California as the cradle of movie stars and endless summers, of a quintessential Americana, and that first trip he was intent on showcasing all that Los Angeles and Orange County had to offer. In five days time, in addition to celebrating Thanksgiving, we swam in the ocean, spotted celebrities on Rodeo Drive, toured the Queen Mary anchored in the Long Beach Harbor, ate at the oldest McDonalds still in operation in Downey, and spent an entire day at Disneyland. The constant pace and activity only amplified my feeling that California was a place to go on vacation but not a state where people actually lived.

Something had changed when I returned later in August. Dad had unpacked his boxes, married, and settled in to his new job. And it was summer: The sun was bright and warm, and the ocean, forbiddingly cold and gray during our first visit, shimmered like a sheet of blue foil. I swam in the Pacific every day. Sometimes, all day. We ate our meals at home rather than at restaurants, often on the little balcony, and whenever Dad wasnt at work he went without a shirt, as he had when I was little. It occurred to me that his old self, his real self, had been pushed underground for the last few years and had finally begun to reemerge in California, fifteen hundred miles from where I spent most of the year. It dawned on me that he was gone and wouldnt be coming back, and the thought of living apart from him, which Id already done for so long, became suddenly intolerable. I wept at the idea, and wept harder at the airport when it was time to fly back to Houston. Id just turned thirteen and could sense the people around me at the gate, watching me bawl. I was embarrassed, but I couldnt make myself stop.

Most boys my age were learning to resent their parents, their dads in particular, and did whatever they could to avoid them. But I was desperate to see mine. I began to hoard small moments of time. Events that would have been mundane under ordinary circumstanceseating dinner, riding in the car, watching TVbecame freighted with importance, simply because I recognized how quickly they would pass, and how long it would be before we saw each other again. The end of that first summer trip coincided with the twentieth anniversary of Woodstock, an event MTV commemorated by airing the original three-hour documentary movie of the festival. Dad and I stayed up late two nights in a row to watch it, and when I got back to Houston I used the money Id made mowing lawns to buy up as much of the music as I could. Not only the big names, like Janis and Jimi, but the smaller acts, like Richie Havens and Country Joe and the Fish and Canned Heat, musicians only the diehards cared about. After school, I lay on my bedroom floor beneath the ceiling fan in the listless September heat, the music spinning in my Discman until I had every song memorized, hoping it would somehow form a tether, like a tin-can telephone, between my father and me.

Next page