ALSO BY G. WAYNE MILLER

Toy Wars

Coming of Age

The Work of Human Hands

Thunder Rise

For Joel P. Rawson, editor, mentor, and friend

This is entirely a work of nonfiction; it contains no composite characters or scenes, and no names have been changed. Nothing has been invented.

The author has used direct quotations only when he heard or saw (as in a letter) the words, and he paraphrased all other dialogue and statementsomitting quotation marksonce he was satisfied that these took place.

Contents

Introduction

Few of the great stories of medicine are as palpably dramatic as the invention of open heart surgery. Few triumphs came at such tragic cost.

I realized this early in writing King of Hearts, when I began to discover the countless peoplemostly babies and young childrenwho died on the operating table after surgeons had opened them up, then been unable to fix their failing hearts. As a father, I understood the desperation that drove parents to entrust their little girl or boy to such a surgeon, who could promise nothing but a heroic effort; faced with terminal heart disease, almost anything was worth a try.

I understood less what motivated doctors to keep trying when so many children perished, literally in their hands. Indeed, many doctors dropped outthe human cost was too high, the emotional toll too devastating. But some persevered. Some, like C. Walton Lillehei, the protagonist of this storythe surgeon whom many call the Father of Open Heart Surgerypushed ahead through all the bleeding and the dying until they finally got it right, only a few decades ago.

How far medicine has come. Today, cardiac surgery is nearly as commonplace as removing an appendix, with almost one million open heart procedures and coronary bypassesand more than 2,200 heart transplantsperformed every year in the United States alone.

And yet, open heart surgery remains a great wonder.

While preparing this book, I watched Richard A. Jonas, chief heart surgeon at Bostons Childrens Hospital, operate on a baby girl; only a week old, she was born with hypoplastic left heart syndrome, in which the entire left half of the heart is essentially missing. Not long ago, this baby would have died in a matter of hours or daysbut Jonas saved her. After the operation, he delivered the news to the parents, whose four hours of waiting is something I hope never to experience. As the parents cried tears of joy, I thought of the countless times in hospitals around the world where this scene plays out every day, for patients young and old.

This is the story of a questa quest that some considered impossible, and others called murderous. Most of it occurred in the 1950s and early 1960s, when jet jockeys piloted the first rocket ships into space.

The best of the open heart pioneers shared much with the early astronauts. These young doctors had returned from war with ambition. They believed in breaking rules, in both their personal and professional lives. They did not recoil from death; they were beyond brave, existing in some rarefied place where taking risks is as fundamental as oxygen.

They were a unique group, these early open heart pioneers: some three dozen or so doctors whose collective contributions launched an infant science. Yet even in this elite group, Walt Lillehei (a Norwegian name, pronounced Lilla-high) stood apart.

After surviving war and then a case of deadly lymphatic cancer, which his mentor cut out of him in an operation that itself nearly killed him, Lillehei seemed to know no fear. He was supremely self-confident, of course, and he was a genius, driven by forces that he himself could never clearly articulate. Lillehei almost certainly lost more patients than any of his peersyet he kept going, perhaps because he was unusually acquainted with death. For even after his cancer operation, Lillehei lived under a sentence: he had only a 25 percent chance of surviving five years.

Far from being embittered, Lillehei was a highly compassionate surgeon; without exception, everyone I interviewed who knew his bedside manner praised it. His young patients and their families idolized him.

Still, Lillehei was hardly a saint; a handsome man with piercing blue eyes, he lived his motto, Work hard, play hard! to the fullestultimately, with terrible consequences for him, his career, and his lovely wife.

I became interested in the story of open heart surgery while researching one of my previous books, The Work of Human Hands, set at Childrens Hospital in Boston, where I met Craig Lillehei, Walts son. Craig is a fine surgeon but a modest person, and he rarely mentioned his father. So while I knew C. Walton Lillehei had played some role in the development of cardiac surgery, I had no idea how important hed been until he came to the Harvard Medical School to lecture in June of 1992. I sat through that lecture amazed, and then I went to the library.

There I found some scholarly books on the history of cardiac surgery, written in academic prose by physicians. A few journalists had also written booksbut none (that I ever found, at least) went much beyond the scientific achievements to the story of desperate patients and families and their daring doctors, the foundation of my narrative.

I present King of Hearts, then, as both a history and a medical drama.

G. Wayne Miller

Pascoag, Rhode Island

October 1999

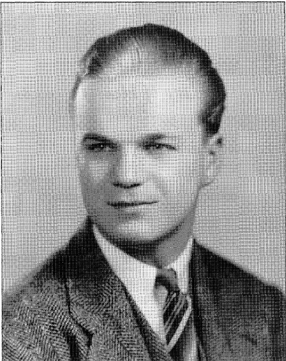

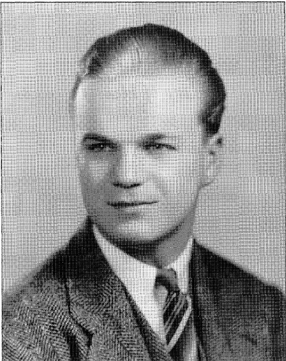

WALT LILLEHEI, MEDICAL SCHOOL GRADUATE

Prologue: Red Alert

O N THE DAY that some feared he crossed over into madness, the surgeon C. Walton Lillehei woke at his usual hour, six oclock. He ate his ordinary light breakfast, read the morning paper, kissed his wife and three young children good-bye, then drove his flashy Buick convertible to University Hospital in Minneapolis. The first patients of the day were already unconscious when Lillehei dressed in scrubs and entered the main operating area. It was March 26, 1954.

Lillehei walked into Room II, where the doctors who would assist him were preparing two operating tables for the baby and the adult who would soon be there. Nearly all of the doctors were youngyounger even than Lillehei, who was only thirty-five. Most were residentssurgeons still in training who were devoted to Lillehei not only because he was an outstanding surgeon, but also because he seemed to live for risk and he overflowed with unconventional new ideas.

Lillehei checked on the pump and the web of plastic tubes that would connect the adult to the baby. He confirmed that two teams of anesthesiologists were ready, that the OR supervisor had briefed the many nurses, and that the blood bank was steeled for possible massive transfusions.