in whole or in part in any form.

SIMON & SCHUSTER and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

The Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

A portion of Chapter 34, Can You Believe It? appeared in a different form in Vanity Fair magazine.

Introduction

IT WAS JUST AFTER SEVEN THIRTY on the evening of October 7, 2005, when Boston shortstop Edgar Renteria grounded out to second base to end the game, and although telephone operators at Fenway Park would continue to greet callers to the home of the World Champion Boston Red Sox for another couple of weeks, the Red Soxs magical runthe one that began in February 2002, when John Henry, Tom Werner, and Larry Lucchino took control of one of the most iconic sports teams in Americawas over. The Red Sox, after winning the 2004 World Series to cap what will go down as the most famous postseason run in history, had been swept in the first round of the playoffs by the Chicago White Sox.

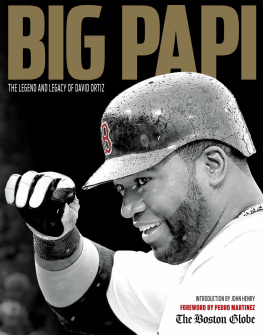

The immediate postmortems would center on that bases-loaded, no-outs jam the White Sox had wriggled out of in the sixth inning, but the air had been let out of the Red Soxs game, and their season, an inning earlier. In the bottom of the fifth, designated hitter David Ortiz came up with two men on and two men out. As he lumbered toward the plate at Fenway, Ortiz was busy mulling over his previous at-bat, when he had finally put the Red Sox on the board with a towering home run to straightaway center field. Now, with the score tied 22, the Fenway crowd began to scream in unison as Ortiz made his deliberate, heaving journey to the batters box: M-V-P! M-V-P! It was as if the crowd felt it could will the countrys sportswriters into granting Ortiz the award if its cheers were loud enough.

Ortiz, who bears a passing resemblance to the cartoon movie monster Shrek, contorts his face into a menacing snarl when hes hitting; it makes him look as if hes preparing to eat the opposing pitcher for dinner. With Johnny Damon, the teams matinee idol of a center fielder, dancing off second base, his wild mane of hair flapping below his batting helmet, and Renteria edging off first, Ortiz uncoiled his mammoth arms and chased after Chicago starter Freddy Garcias first offering. The bat hit the ball sharply thwack! and, at first, it seemed to mirror perfectly the trajectory of Ortizs fourth inning shot. The crowd leapt to its feet with a roar. But as strong and powerful as Ortiz is, not even he can push a ball out of the deepest part of the park when he doesnt connect dead on, and his bat had gotten just under this ball. As he dashed for first, and Damon rounded third, the ball arced through the crisp Boston air and fell, finally, into Aaron Rowands glove in center field. Inning over.

Ortiz stopped about 20 feet from first base and froze, staring blankly at the spot where his blast had died. He stayed there as the White Sox jogged off the field. He stayed there as his teammates began taking their defensive positions around him. It was as if he couldnt believe that this time, in this at-bat, he hadnt been able to come through. The Red Sox had to win this gamedidnt they? They had all the trappings of a championship team, including a $127 million payroll, the second highest in baseball. (The Yankees, the perennial bullies down the block, led the field at $208 million.) They had a roster full of All-Stars: Manny Ramirez, the slugging left fielder who was often described as the best right-handed hitter in the American League; Jason Varitek, the unassuming catcher who was known as one of the premier pitch-callers in baseball; and, of course, Damon and Ortiz. They had what was commonly described as the smartest front office in the business and an ownership group that seemed as devoted to fielding a winning team and giving back to the community as it was to making money. It was a recipe that was supposed to all but ensure success.

Indeed, since Henry, Werner, and Lucchino had taken over, being a Boston Red Sox fan, once a pastime best suited to masochists and depressives, had become fun, exciting, even trendy. Henry, the shy commodities trader, brought the same faith in statistical analysis to his baseball team that he did to his work in the markets. Werner, the television executive responsible for hits like The Cosby Show and Roseanne, helped ensure that the Red Soxs regional sports network, the New England Sports Network (NESN), raked in revenue. And Lucchino, the hard-charging former litigator, was an uncommonly creative chief executive known for never resting on his laurels and having a keen eye for emerging front-office talent. He delighted in fostering and developing smart, young leaders, most notably Theo Epstein, the 31-year-old Bostonian who became a folk hero when he was named the teams general manager before the 2003 season.

Together, Henry, Werner, and Lucchino had taken an organization known primarily for its heartbreaking losses and perennial runner-up status and transformed it into a world champion. Gone were the days when the team failed to sign Jackie Robinson or Willie Mays because its owner and its general manager were racists. Gone were the days when Carlton Fisk, a New England native and one of the best catchers ever to play the game, was lost to free agency because the Red Sox front office neglected to mail him his contract on time. Gone were the days of owners not speaking to management, of management not speaking to the coaching staff, of the coaching staff not speaking to the players. Gone was the Curse of the Bambino, the specter of Bucky F-ing Dent and Billy Buckner. Even the notoriously combative Boston media seemed to have been pacified by the teams press-friendly policies and winning ways. The Red Sox of old might have fielded a team of whining, overpaid misfits who got swept in the first round, and in the old days, that sort of failure would be followed by a course of inevitable finger-pointing and recriminations, whether deserved or not. But that wouldnt happen now. These days, things were different.

Werent they?

It had been just five years earlier, on October 6, 2000, that John Harrington, then chief executive officer of the Red Sox, announced that, for the first time in a generation, the team was up for sale. Harrington was the last direct link to Tom Yawkey, the millionaire playboy who bought the Red Sox in 1933, and whose name now graced Yawkey Way, the street on which the entrance to Fenway Parks offices were located. Yawkey died in 1976; his wife, Jean, helped run the team until her death in 1992, at which point Harrington, one of Jean Yawkeys closest confidants, took control of the Jean R. Yawkey Trust, which by 1994 owned a majority stake in the team.

At first, the timing of Harringtons announcement seemed odd. The Red Sox had just emerged victorious from a grueling legislative battle that all but guaranteed the construction of a new, modern ballpark to replace Fenway, the oldest, smallest, and least comfortable place to watch a ball game in the whole country. But Jean Yawkeys will had compelled the trust to put the team up for sale eventually (the profits would be used to endow the charitable Yawkey Foundations), and the Red Soxs value was at an all-time high. Attendance was up, baseball had recovered from the labor dispute that had led to the strike that canceled the 1994 World Series, and the Red Sox were stocked with exciting, top-tier talent, including pitching great Pedro Martinez and homegrown superstar shortstop Nomar Garciaparra. In the press conference announcing the sale, Harrington said that, above all else, he hoped the team would go to a local bidder. God willing, Harrington said, my last act will be to turn this incredible team over to a die-hard Red Sox fan from New England who knows how important the team is to this town and the fabric of this community. In an article the next day, The Boston Globe noted that Harrington would, of course, be willing to listen to bids from outsiders.