Mortimer - The Outcasts of Time

Here you can read online Mortimer - The Outcasts of Time full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: London, year: 2017, publisher: Simon & Schuster UK, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Outcasts of Time

- Author:

- Publisher:Simon & Schuster UK

- Genre:

- Year:2017

- City:London

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Outcasts of Time: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Outcasts of Time" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Outcasts of Time — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Outcasts of Time" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

This book is dedicated to my son,

Alexander Mortimer

Home is not a place but a time

Chapter One

Tuesday, 16 December 1348

The first thing you need to understand is what it means to sell your soul. It is not a matter of shaking hands with a shadowy figure, or bartering promises with a burning bush. What do you have to sell? You dont know. To whom are you going to sell it? Again, you dont know. All you know is that your very desire to offer it up is accompanied by the most overwhelming urge to scream. You want to scream so much that you will empty your bones of time.

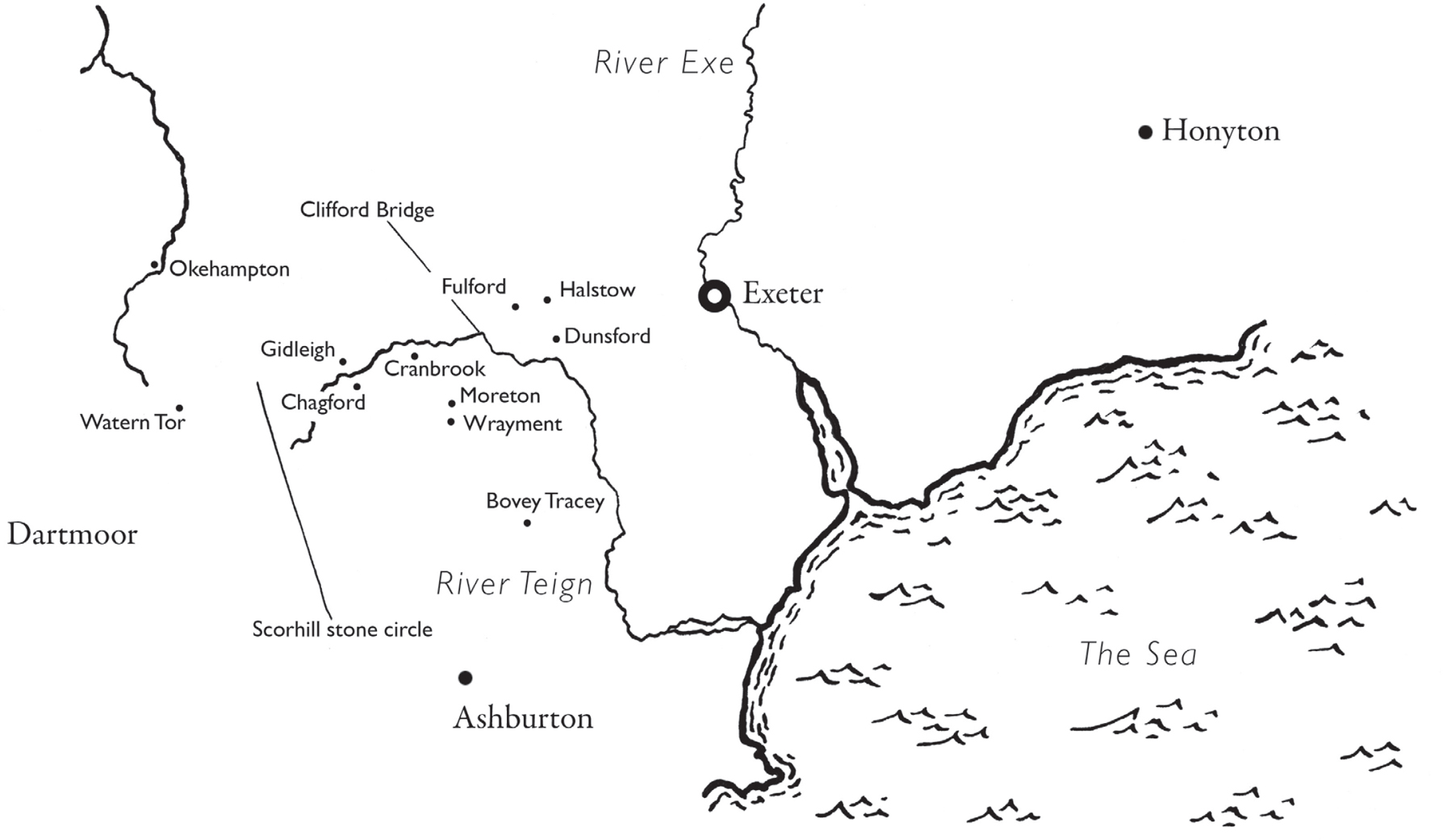

This is what I feel now and have felt every day since I first saw the deadly work of the plague. When I look along the road into the distance and see no one, the desire to yell burns within me. When I look up towards the hills where once there was peace and tranquillity, I think of a horrific silence: abandoned farms and cottages, the carcasses of animals and the bodies of children and their parents. The absence of kindness. An eye without life. Now, as we approach the leafless oak on the edge of Honyton, and the inn beside it, the urge to cry out is overwhelming.

There were musicians playing when I was last here, three days before Michaelmas. That was just eleven weeks ago. I stop and let my travelling sack fall to the ground, and put my face in the hollow of my cupped hands; I whisper the names of my dead mother and father. My brother William turns and tells me to hurry, and makes a joke about me being slower than the dead. I take my hands away from my face, and stare at him, then pick up my sack and start walking again. But inside I am still yelling. I can do nothing to tell the world how I feel because everything is dying around us. And dying inside us.

I glance back at the leafless oak and remember the scene that day: the music and the gaiety. We were travellers passing through the town, watching the women and girls dance with the men, their hair let down, naturally flowing. They all had their favourites: you could see their loves in their eyes as they skipped past them. They were smiling at us too, as if they understood that we strangers, by watching their smiles, knew the secrets of their hearts. I remember slopping my ale cup and singing lustily, even though William and I had been intending to leave earlier, on our journey to Salisbury. Now, looking at that tree, I wonder how many of those women are dead. It seems that winter has twice fallen. Firstly, it has come upon us with the chill of December: in the bare branches stark against the sky, and the short days and the frozen puddles in the ruts of the roads. And secondly it is here in the crow-cry of cold despair, and the feeling that, unlike any previous year, there never will be another spring. Winter is a point of reckoning now, not a pause.

Time there was when the marketplace in Honyton was all colour and movement. On market days youd see the russets, browns, greys and reds of tunics, and a whole gamut of hoods and hats. If you blurred your eyes for a moment, youd see it like the movement of a hive, as if all the little twitches of the crowd were bees. Thered always be a still point in the human storm: a crier calling the news or a black-cassocked friar haranguing a group of youths about their souls struggle to reach Heaven. Today there are no criers, friars or tormented souls. There are no market traders either no nodding hoods as a butcher or piemaker passes over his wares and holds out a hand for the silver pennies, turning immediately to greet the next customer. Dead leaves blow across the mud and gravel of the square. A broken trestle from a stall lies on its side, commemorating the last market to be held here. It looks like an old tilted grave marker where someone who has already been forgotten lies buried.

William and I continue along the street through the town. Its still early, the third hour after prime, but both of us are tired after a restless night under the dripping trees. House after house has its shutters closed, as if the townspeople are still in bed.

How many corpses do you think well see today? asks William, adjusting the travelling sack on his shoulder. Ill hold you, itll be more than yesterday. What do you say, John, more than six? A kiss of Elizabeth Tappers honeyed lips and a jug of her best ale, for he who counts the most this side of Whymple.

I look at my brother but I do not reply. I see the gold ring with the garnet that he always wears, his most prized possession. He seems to think that, apart from the unfortunate victims, life is the same as ever.

Oh, come now, brother, he says, I pray, speak! Youre not dead yet. The heaviness of your mood is such that anyone might mistake you for Noah on his Ark, in the moment of realising that hes forgotten the cows.

Jest not, William. This is a second Flood. God is clearing the land. Not with water but with pestilence. Can you not see it?

Dont be a cut farthing, John. What I see is what you see. No more, no less. But your mind is closed. This pestilence is no work of Gods. Weve seen young children, babes even, lying by the road with black blotches on their necks, arms and thighs. Why would God be punishing them? They cannot have sinned. This is no divine clearance of iniquity. This is the work of the Devil, and Ill not be awestruck by it.

I take a deep breath. William, the Devil is Gods vassal, and the Devil shall do what the Lord Almighty commands him to do. If God wills the land be cleared of sinners, then the Devil shall do the clearing. Those who fail to attend church are...

But William, looking ahead, raises his hand.

The body is that of a grey-bearded man in his fifties, lying face down on the hard earth and stones of the highway, with his head turned to one side. There is a sagging black swelling on the lower side of his neck, the size of two fists clasped together, clutching at his throat. His mouth is open slightly; the whiteness of his teeth only draws attention to the fact that at least two are missing. William presses his foot against the mans cloak: it is frozen stiff. One knee is dirty where he fell. His purse has already been cut from his belt and the moistness of his eyes has frozen, glazing his expression into an opaque whiteness.

Normally, on finding a dead man, we would go to the constable. But today we remain quiet.

Hes nothing of beauty, thats for sure, says William, turning away.

He was one of the lucky ones, I reply as we walk on. I scratch an itch under my arm.

Lucky? Listen, brother, if that mans fate be fair good fortune, my horse speaks Latin. By what token was he lucky?

He fell face down. He did not spend days suffering, sweating and frenzied. He was able to walk until finally he collapsed. He used a cuttlefish to whiten his teeth; therefore he must have been a man of some prosperity. As for his cloak, even you would be proud of such a garment. Last, look at where his purse was. Clearly, the man who cut it from his belt opened it and saw not one or two coins but many enough that he decided to take the risk and cut the whole purse, even though it might be carrying the infection. So, brother of mine, I say to you that this wealthy man, suddenly taken ill with the disease, choking on his pain and stumbling to a quick death, was most fortunate.

William shakes his head. You should not attend so closely to the death throes of every stranger, John. Let some of the dead suffer on their own account.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Outcasts of Time»

Look at similar books to The Outcasts of Time. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Outcasts of Time and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.