Contents

Guide

O rcus was a monster originally invented by the Etruscans to stoke the fires of Hell. He later emerged as the ogre of fairy tales, fond of eating the flesh of children, among other bad food choices. The slobbering orc in Tolkiens Lord of the Rings is probably the most recent manifestation of this archetype.

With all this in mind, orca is an odd choice of name to give to a new best friend, but the alternative, killer whale, seems even more defamatory to their many admirers.

Outside of the ranks of sailors and whalers, little was publicly known about Orcinus orca until the mid-1960s, when young orcas began to be captured alive for aquariums. Up until then most folk would probably have gone along with the view expressed by Pliny the Elder, who long ago dismissed them as mountains of meat with teeth.

When the first captive orcas were installed in tanks and harbour enclosures, the biggest surprise for aquarium directors, apart from the large amounts of money to be made from having one as an attraction, was just how docile and friendly the toothy giants turned out to be. It was even possible to plop scantily-clad young women into the same pond without fear that they would be touched inappropriately, let alone snapped up like canaps. This was precisely the kind of man-bites-dog story that appeals to the popular press, and word soon spread. Ticket sales soared and, to meet the burgeoning demand in the 1960s and 70s, more and more orcas, virtually all juveniles, were snatched from the sea.

This sorry episode in the inglorious saga of humancetacean relations came to an end at about the turn of the century. Audiences and keepers alike began to realise that orcas werent just titillating monsters but highly intelligent and sensitive creatures, with moods and emotions as complex as ours. Despite their cruel confinement, they behaved far better towards us than we did towards them. Keeping them in swimming pools was a very bad idea.

Public interest helped inspire and fund intensive research, and one of the first major findings was that there were far fewer killer whales in the worlds oceans than had been supposed. The population in the Pacific Northwest, which had been the aquariums principal source of young orcas, amounted to a few hundred at best.

Killer whales are not whales of course, but the largest member of the dolphin family. Despite their being black and white and found all over, we are also now told that there are several different types. Recent research, particularly in the Pacific, has suggested that at least two variants exist: the transients and the residents. Transients seem to wander the seven seas and prey mainly on marine mammals, especially other dolphins, porpoises and whales. Residents, as the name implies, are committed homebodies, stay in the same locale year-round, live in larger family groups or pods, eat mainly fish and never ever take a vacation. The different types seem largely to ignore each other and have even evolved their own dialects of the orca language.

Whatever the cut of their jib or the tone of their voice, killer whales are apex predators, with nothing to fear in the sea. Killers they certainly are, but no more so than a lion or a tiger. The enduring mystery, especially given how weve behaved when weve met them in the wild, is that they havent taken every available opportunity to chow down on some of us.

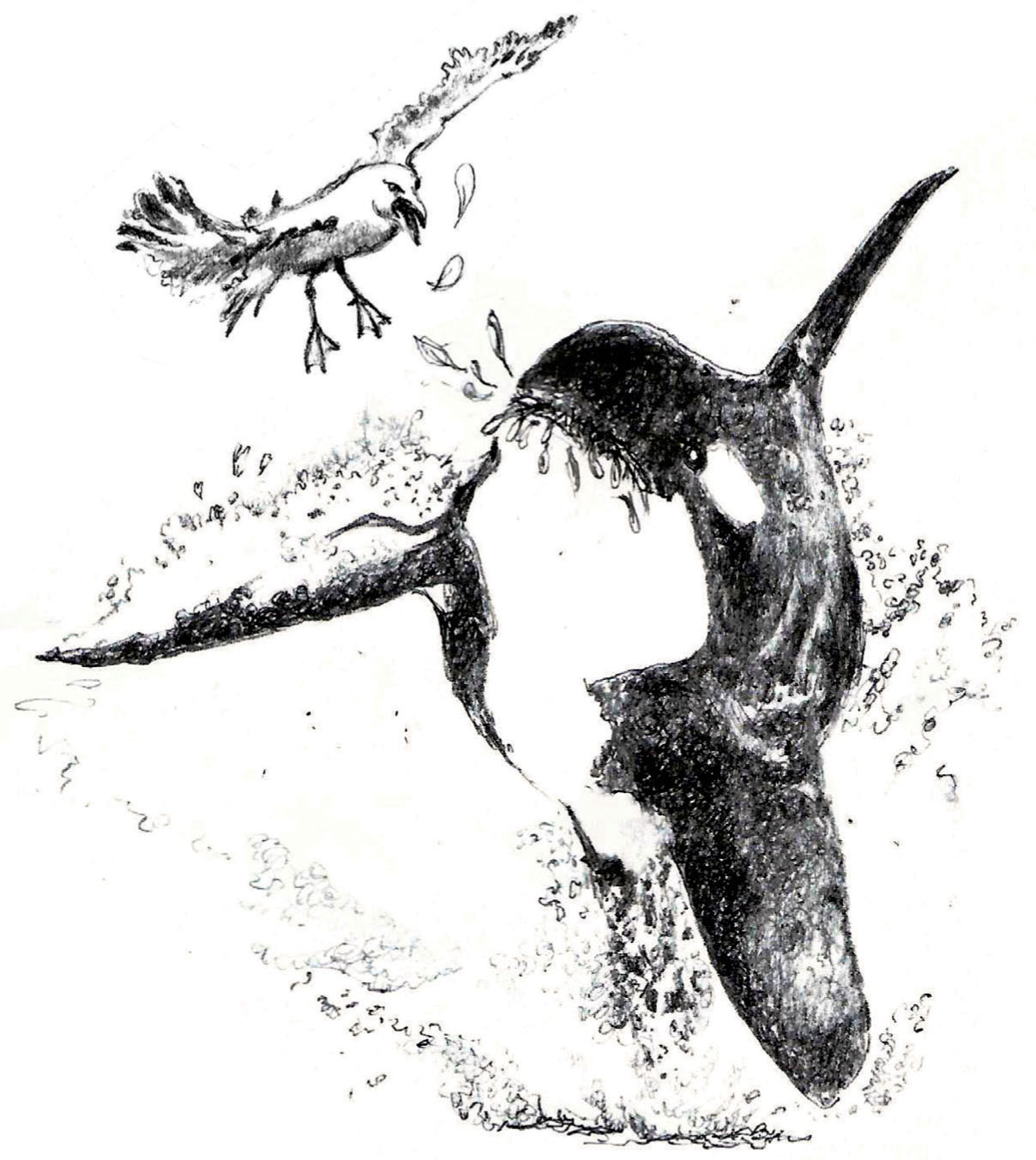

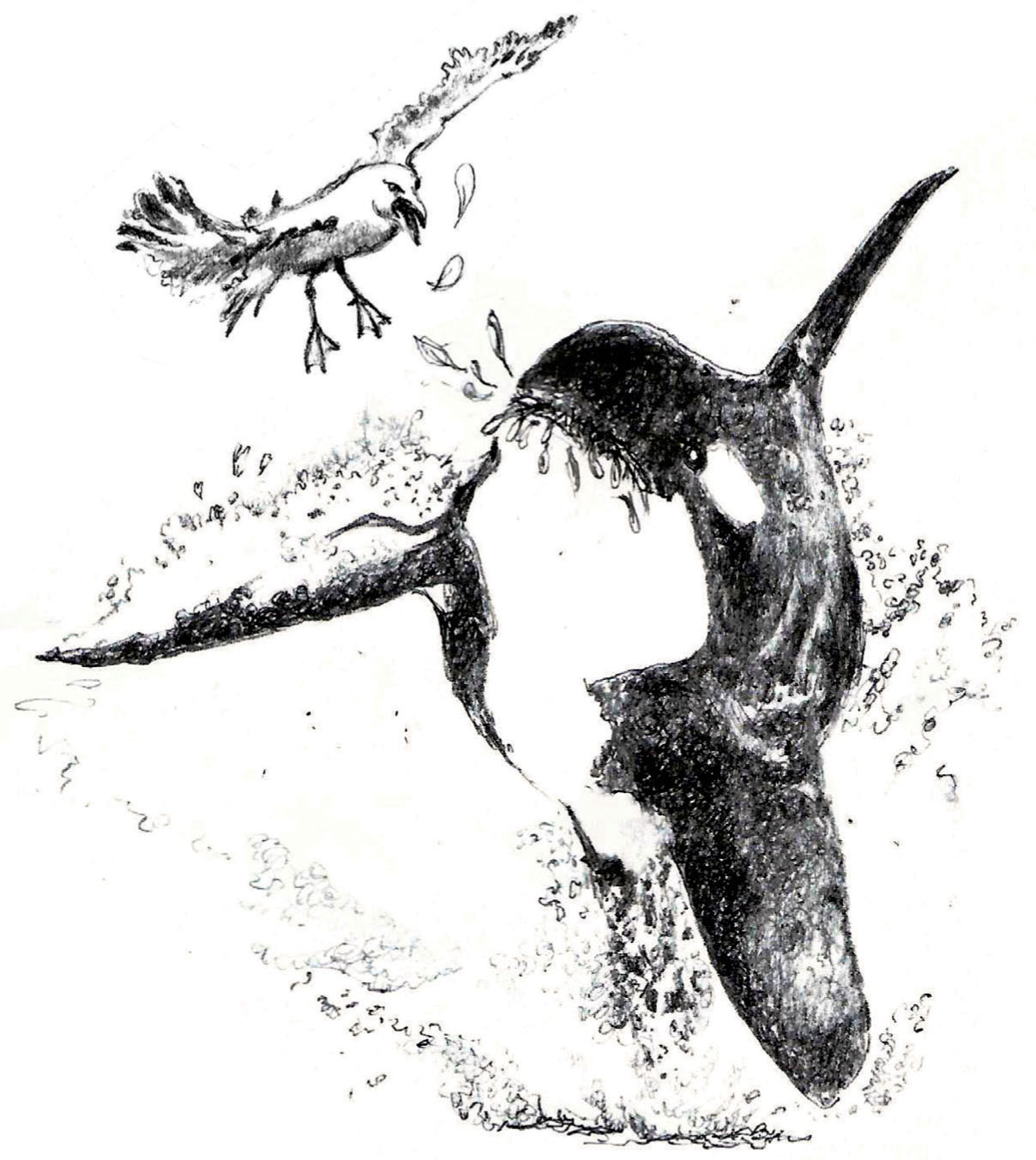

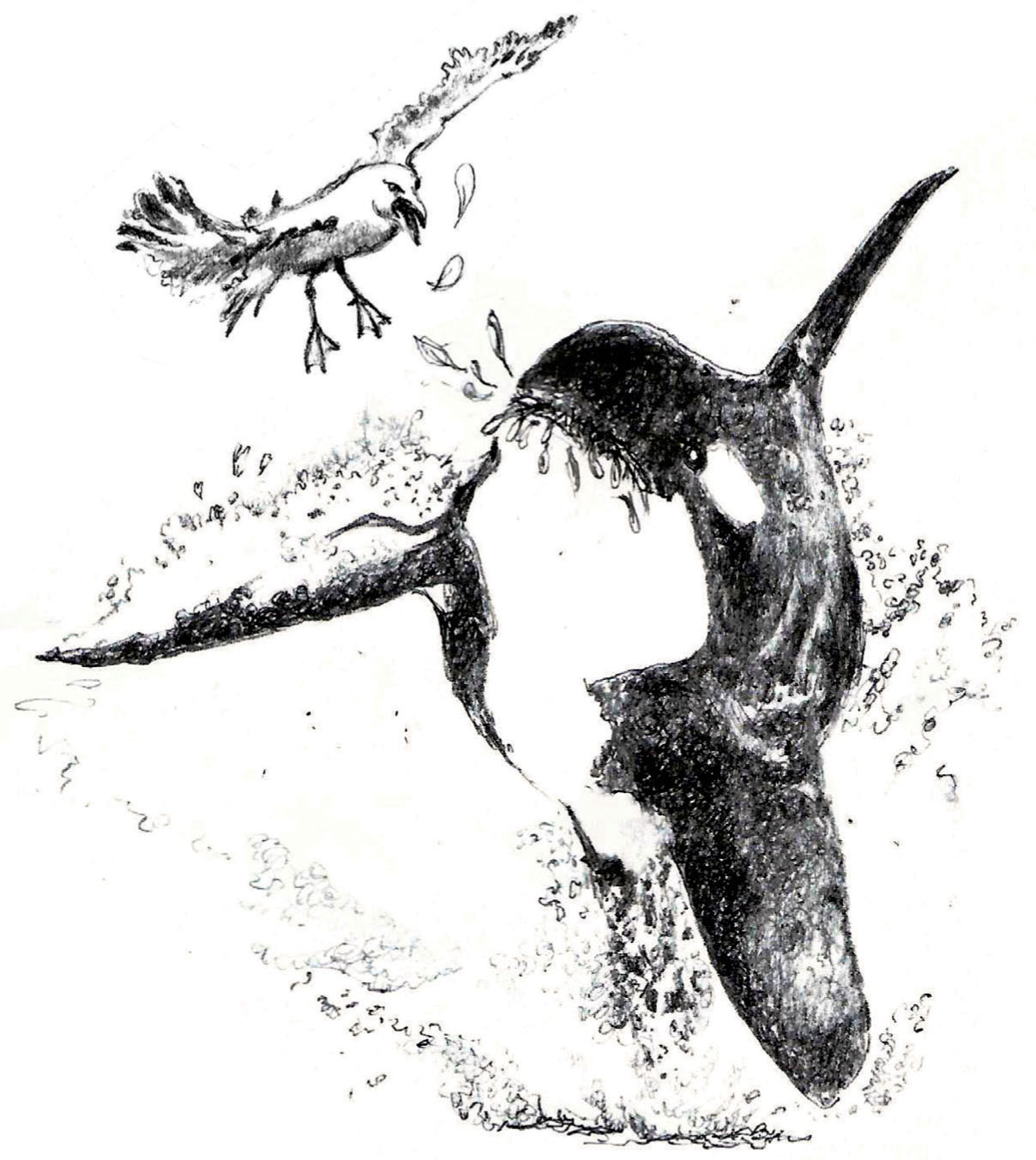

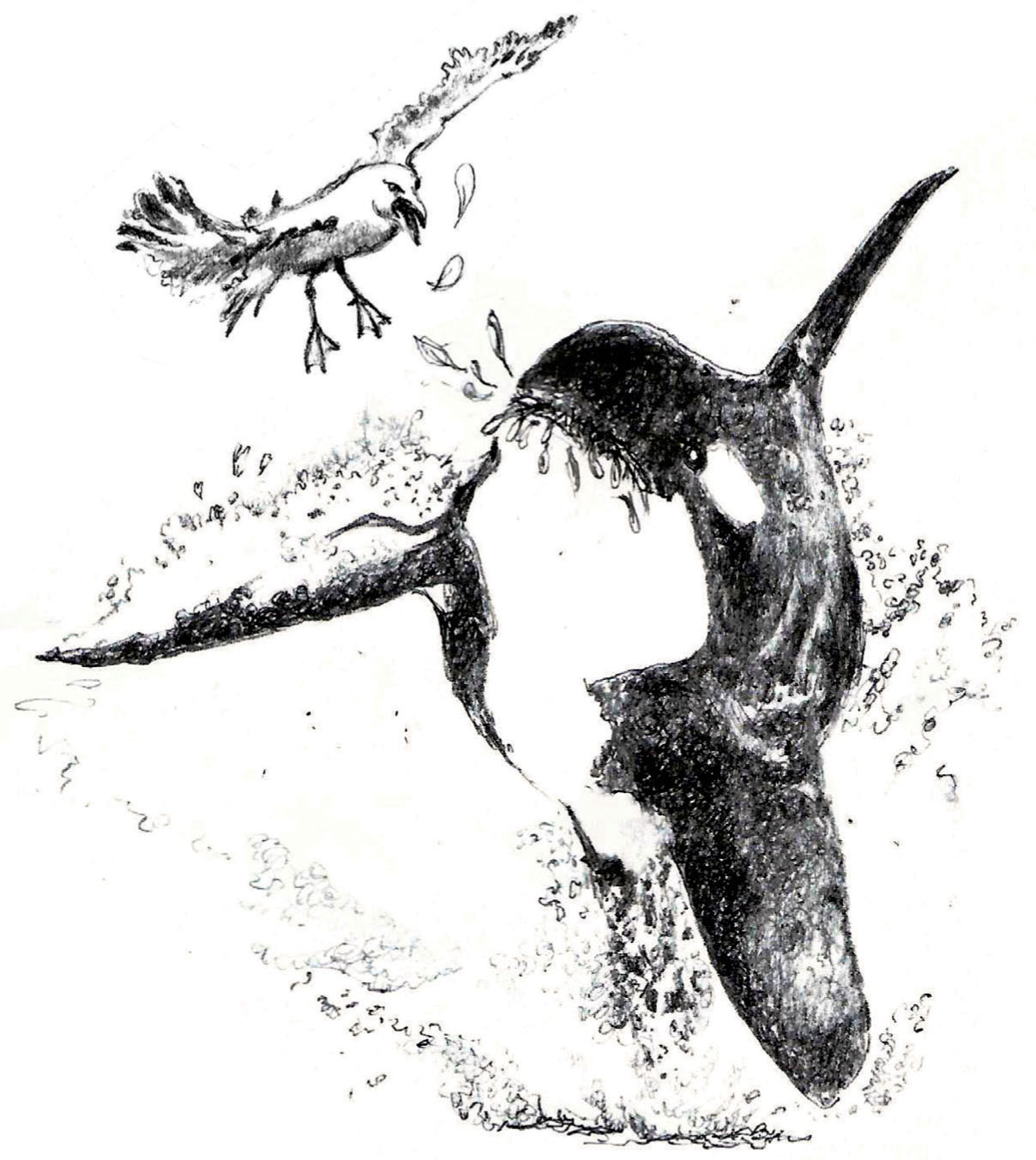

Its not as though theyve never been exposed to terrestrial food. Theyve been known to grab seals from pebbly beaches, dislodge penguins and polar bears from ice floes, and even snap up the occasional astonished elk swimming a Canadian river. Flipping a canoe, or even a sizeable yacht, to get at the titbits with the quivering jelly centres they contain, would be no real challenge. But theyve never, barring the occasional aquarium accident, so much as nibbled a single one of us.

A possible answer is that they see us as kindred spirits, or at least as useful idiots. For several decades prior to the demise of the whaling industry, killer whales in the seas off the south coast of New South Wales, Australia, herded humpback whales into a bay near Eden so that whalers could more easily kill them. Their reward was the tongue and the lips, seemingly their favourite cuts. Its difficult to decide who was using whom in this instance, but the relationship went sour when the whalers eventually reneged on the deal and the orcas went off in a huff. Similar stories have arrived from other parts of the world, with the embellishment that orcas occasionally fend off sharks when they try to attack shipwrecked whalers and fishermen.

Putting our conceit aside, in these latter cases (if they happen), its more likely that the orcas were after the sharks anyway, a favourite prey species. An unspecified number of killer whales recently weighed into the population of great white sharks in South Africas Walker Bay, much to the consternation of the proprietors of the local shark cage-diving industry. They killed at least three great whites, eating their livers and discarding the rest, proving, if nothing else, that they are choosey about their food, and sometimes wasteful eaters.

They have that in common with most of us and, despite the huge physical disparities, a lot else besides. Other than humans and short-finned pilot whales, orcas are the only known species in which females go through menopause. Various theories have been developed to explain this strange evolutionary quirk, but it seems to be linked in a complex way to longevity, cognition and the importance of familial relationships for survival and success.

Like all dolphins, in addition to their excellent eyesight, killer whales use ultrasound to form a detailed picture of the world under water. Captive orcas, like other dolphins, have purportedly been able to tell when a woman swimming in their tank is pregnant, even if she is in the earliest stages. With such skills, they probably saw through our species long ago. Given their affable attitude towards us, we can only assume that they discovered, in a dark recess, the seed of something worth preserving.

O ld Africa knew the springbok by other names, all of which loosely translate as ray of the sun. The gazelles were especially favoured by the sun god who imbued them with magical powers. One happy outcome is that dreaming about a herd of springbok cavorting on the vast, ethereal plains of the Great Karoo yields the dreamer a promise of great wealth.

When it comes to sheer good looks, theres no doubt that the springbok is a crowd pleaser. If there ever were an event as bizarre as an inter-species beauty contest, many a lass, alas, would run home to her mother in tears. Graceful, slender and long-legged, with a snow-white face, a golden coat and bold side stripes, as well as other more subtle cosmetic touches, these antelopes seem to know they were really born for the swanky salons of Paris, London and Milan.

When excited or frightened and sometimes, it seems, just because theres an audience, they repeatedly bounce into the air, 2 metres and more, back arched, hooves bunched and legs held stiffly together, as though theyre on pogo sticks. As part of this dramatic routine, the flap on their rump inverts into a fan of dazzling white hairs, more than worthy of a headline act at the Moulin Rouge. The whole performance is known as pronking, derived from an Afrikaans word which, if you ignore the professorial chit chat, means showing off .

Next page