Contents

Guide

The Guga Hunters

Donald S. Murray

This edition first published in 2015 by

Birlinn Limited

West Newington House

10 Newington Road

Edinburgh EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

Copyright Donald S. Murray 2008, 2015

The excerpt from Seamus Heaneys Kinship is reproduced by permission of Faber & Faber

The moral right of Donald S.Murray to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication maybe reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

ISBN: 978 0 85790 765 3

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Typeset by Iolaire Typesetting, Newtonmore

Printed and bound by Bell & Bain Ltd, Glasgow

The Guga Hunters

Donald S. Murray was born in Ness in the Isle of Lewis. An author and journalist, his poetry, prose and verse has been shortlisted for both the Saltire Award and Callum Macdonald Memorial Award. Together with a Creative Scotland award for travel and research in 2014, he has been awarded both the Robert Louis Stevenson and Jessie Kesson Fellowships in recent years. His work has also appeared in a number of national anthologies and on BBC Radio 4 and Radio Scotland. He lives and works in Shetland.

To the people of Ness

Far an d fhuair mi m rach g

And in memory of

Murdo Deedo Macdonald (19652008)

a very special Guga hunter

to whom this work owes so much

Murdo Angus Murray (195588)

Angus Amos Murray (195691)

Norman Smith (Tormod Sguigs),

who passed away on 31 December 2014

report us fairly,

how we slaughter

for the common good

Seamus Heaney, from Kinship

Contents

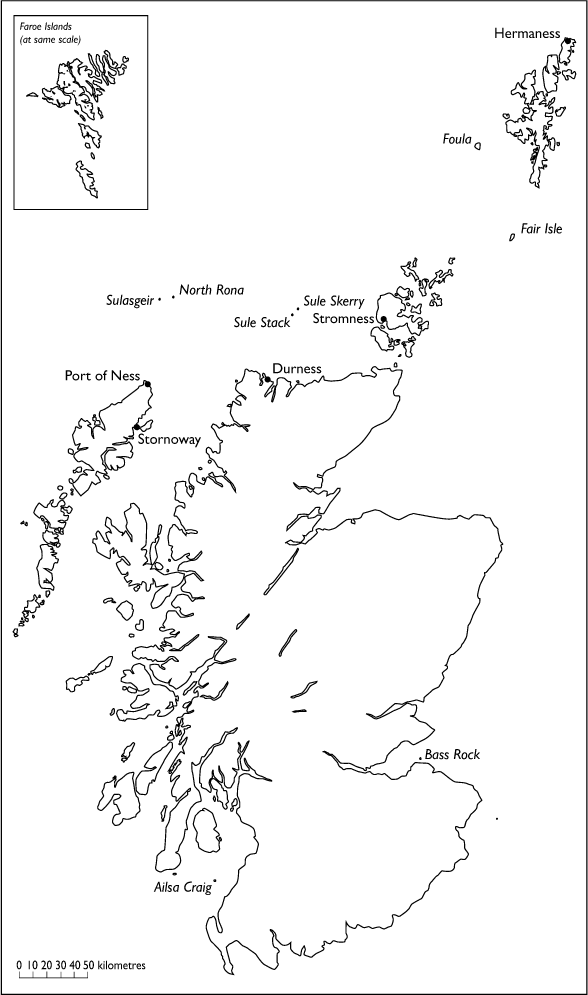

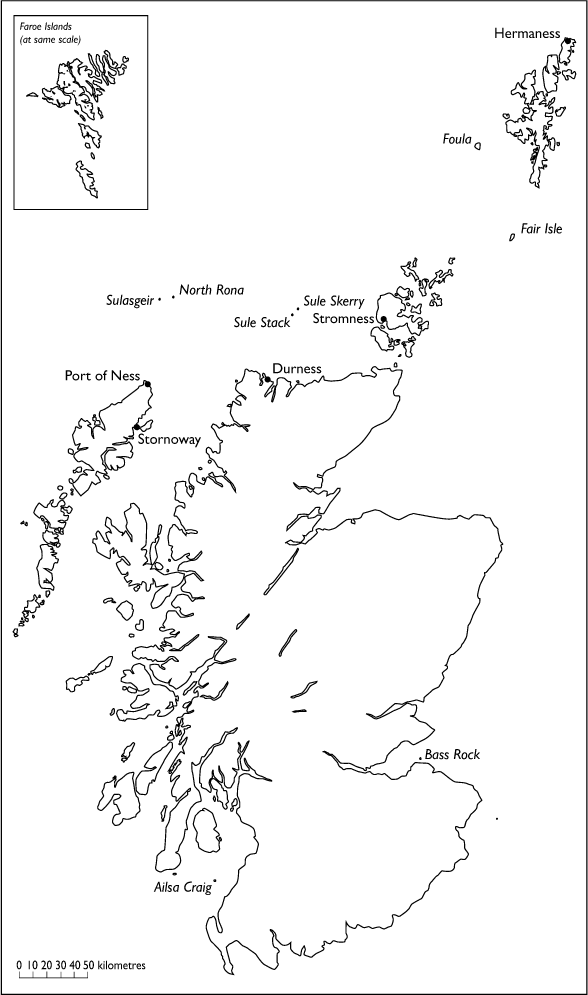

An incomplete map of Scotland from the gannets point of view

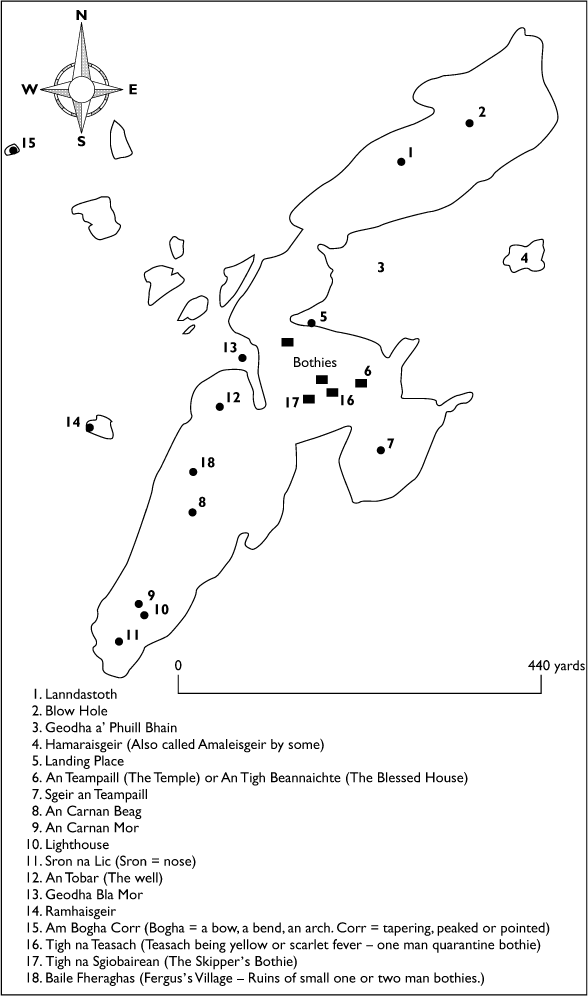

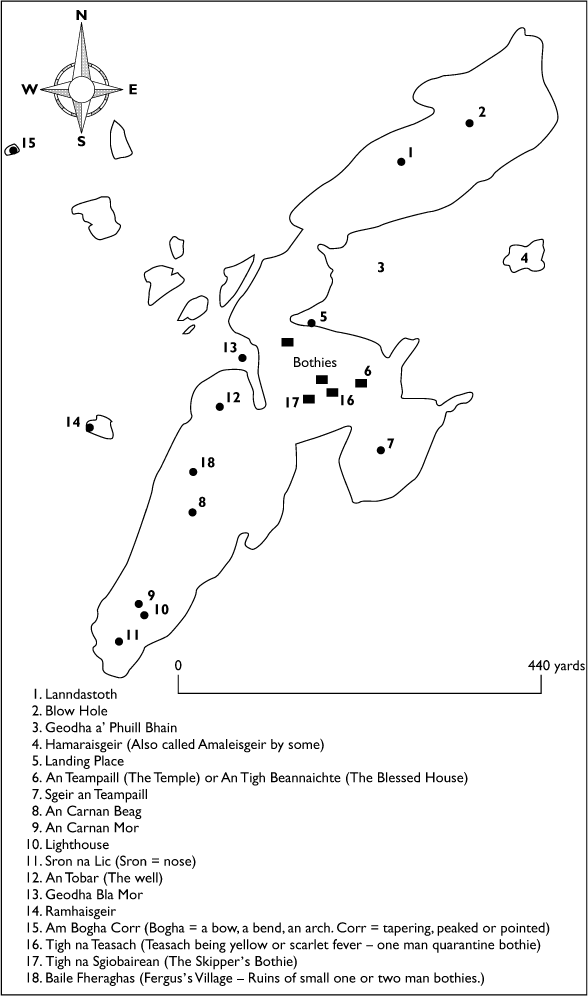

A map of Sulasgeir from a guga hunters point of view

Frontpiece

Ceyx and Alcyone

As the daughter of Aeolus, king of the winds, Alcyone knew only too well what happened sometimes to ships at sea. It was for this reason that she quarrelled with her husband Ceyx, the king of Thessaly, when he told her he was going on a long voyage to consult with an oracle about a matter of state. For the first time ever, she argued with him, demanding that he should not go or, if he insisted on his journey, that she should come with him. Though he loved her very much, he shook his head. He would have to go alone.

That night, there was a great storm. Together with his entire crew, Ceyx drowned, the word Alcyone on his lips as the waters closed over his dying body. Unaware that his life had ended, his wife walked every night to Heras temple, praying for her mans return. The goddess heard her prayers and was touched both by her faith and her fidelity. With the assistance of Morpheus, the god of sleep, she sent an apparition in her husbands form to Alcyones bed. Your name was on my lips when I drowned, he declared. Accept this and give me your tears. Do not force me to step into the shadows without them.

Wait for me. I will go with you, she cried, but he faded into the darkness, escaping her outstretched hand. The following morning, aware for the first time that he was dead, Alcyone walked to the shore. Staring out, she noticed an object floating towards her, coming to rest on the sand. She ran towards it, aware suddenly it was her husbands body. Curling her arms around him, she wept bitterly.

It was a sight that prompted the gods to pity. Ceyx and Alcyone were given new lives, transformed into birds. Ceyx was granted the white wings and yellow head of a gannet; Alcyone the magnificent shades of a kingfisher. One was given the width of the ocean to command; the other the banks and shallow water of a riverbank. Yet on occasional days of stillness and calm the halcyon days of summer the two birds still meet above the ocean.

The gannet greets his former lover with her name. Alcyone... he says.

Introduction

Fifty-Nine Degrees North; Six Degrees West...

Men have been killing and eating seabirds since long before the Classical Age began.

It is a practice that has been going on since our early ancestors lived in caves that even today tunnel some of our shorelines. They would emerge from these, perhaps with club in hand, seeking to appease the hunger that so often must have drummed and boomed within their empty stomachs, seeing an opportunity to do this in some of the wings that flashed and trembled before them among rocks and crags. The jet-black plumage of the cormorant. The grey feathers of a gull. The awkward, almost comic flight of the puffin. And, of course, the magnificence of the great bird that is most often seen plunging like a white blade into the dark waters off our coast the gannet, also called the solan goose.

It is a tradition, too, that has occurred throughout the globe. In Tierra del Fuego at the southern tip of South America, seabirds were hunted and eaten by the native Fuegan people; their catch drawn down by a long slender rod with a noose attached. At the other end of that great continent, the indigenous population of Alaska performed the same task with similar methods, trapping sea-fowl sometimes, perhaps, with the use of bait or stones or even fingers. The custom, too, has been followed in places as far apart as Hokkaido, the most northerly island of Japan, Novaya Zemyla, the former gulag of the Soviet Union in the Arctic Ocean, Newfoundland and the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa.

Yet it was probably most common on the edges of the Atlantic in northern Europe, in the places occupied by both Norseman and Celt. Their locations ranged from Greenland in the far north to the Blasket islands off the southwestern edge of Ireland and many other coastal settings scattered east, west and in between. Much of this has to do with the waters of the North Atlantic, especially from 50 degrees, or Lands End, at the southern tip of England, northwards. The ocean in this area is comparatively shallow, with large areas, such as the majority of the North Sea and the entire Baltic Sea, lying on the Continental shelf. The fact that cold and warm ocean currents meet there also makes it ideal for the close partnership of plankton and fish that provide necessary links in the food-chain for seabirds to live and thrive.

Geologically speaking, there are other factors that make these areas ideal residences. Not only is food readily on hand (or foot or wing), there are also ready-made dwelling-places for the birds. These come in the shape of certain cliffs. Perfect for a number of reasons, many jut out over the oceans and offer horizontal ledges and small alcoves within the rock on which the birds can nest. In addition, they offer vantage points from which they can survey the oceans, spotting any likely shoals swimming in their direction. They provide a little shelter from the full force of the wind, allowing creatures that are more graceful in flight than take-off to leave their nests with a certain degree of grace and security. They grant safety, too, from predators that are all around them. These include mammals like seals, otters and polecats, and also feathered visitors, such as the skua or gulls, that tend to settle on flatter, less wave-buffeted land elsewhere.