In memory of all the nameless people who die with their dreams crossing the Mediterranean Sea every year.

For Nicholas and Matthew

Contents

Introduction: Setting the Compass

When I moved to Italy with my husband in February 1996, I admittedly knew nothing about this country. We were newly married and had left South Dakota in the American Midwest on a blustering snowy day with wind-chill temperatures hovering around forty degrees Celsius below zero. The sight of the green rolling hills and deep blue sea below our TWA 747 as we landed at Romes Fiumicino Airport was nothing short of magical. The taxi driver even whistled Smoke Gets in Your Eyes as he drove us through the cobbled streets of the ancient eternal city with which I would soon fall in love. Twenty years, two sons and one less husband later, this country still captivates my soul. It delights me and infuriates me, but mostly it still challenges me to reconsider everything I assume to know. Nothing can be taken for granted in a place with such a complex past, and the rules I was used to in America have never applied here.

Not long after we arrived, I landed a dream job with Newsweek magazine , which gave me a front-row seat to the events that were unfolding around me. The European Union was just launching its single currency and Italy was modernizing in ways both good and bad to try to keep up. When I first arrived, everything was closed on Sundays and you could scarcely buy milk and flour in the same store thanks to protectionist laws that kept small businesses alive. Now the quaint, family-run businesses have largely disappeared, giving way to Chinese discount shops and twenty-four-hour grocers. Italy was a true monoculture back then; most of the foreigners were tourists or white expats like me. That has changed, too, with the influx of migrants and refugees coming into the country by sea; more than 181,000 mostly Africans arrived in 2016 alone, creating what is referred to simply as the migrant crisis, even though many of the people coming over are also refugees in the truest sense of the word, fleeing war and persecution. Few will ever be allowed truly to integrate into this society; they are rarely allowed to work behind the counters in the shops; instead, they seem destined to stand in front of them begging for loose change.

I have covered all sorts of stories during my time here, from lavish papal coronations to mass-casualty earthquakes. Ive lost count of how many governments have fallen and how many leaders have been forced out of office in shame. There have been murder trials and cruise-ship wrecks and gala parties inside ancient monuments, but the most common storyline that I have covered is one that seems to be the subtle thread running through every major event in this country: Italys endemic corruption.

It would be easy to blame this malady entirely on the countrys major organized crime syndicates such as the Sicilian Cosa Nostra, the Neapolitan Camorra or the Ndrangheta of Calabria but it extends far beyond the mob. I have seen corruption in local and national government institutions and public schools, in the Catholic Church through the widespread cover-ups of clerical sex abuse crimes, and on my street when a traffic officer takes a bribe and tears up a ticket. But lately it is most apparent in the mishandling of the migrant crisis through the blatant exploitation and blind eye turned to whats happening to some of the most vulnerable people on earth.

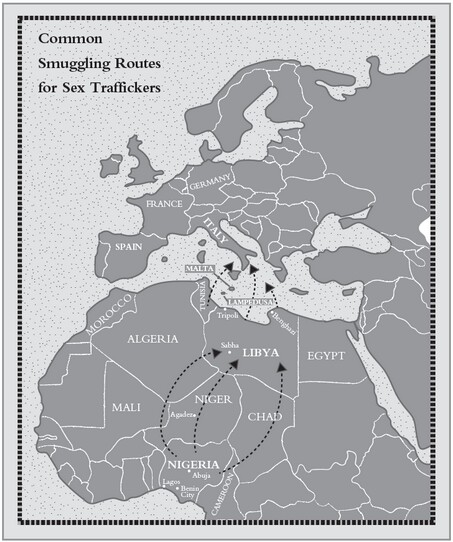

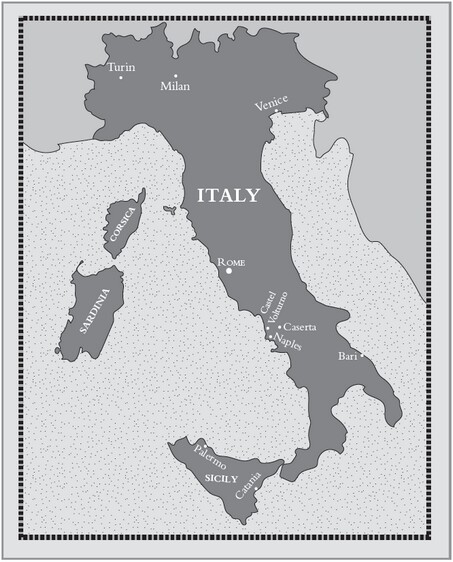

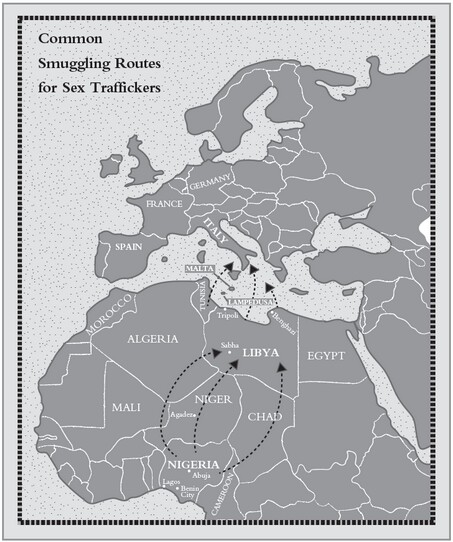

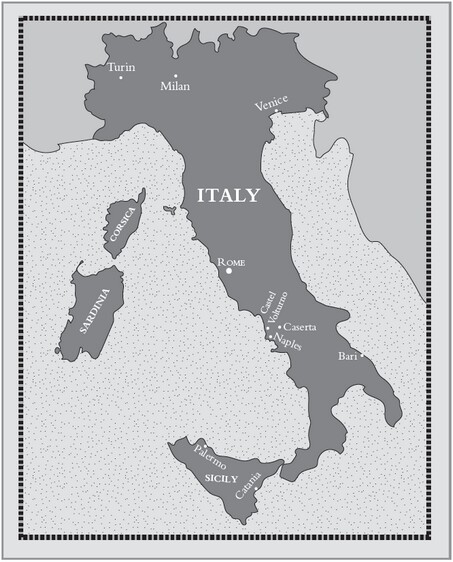

When I think back to the first time I saw Italy from above, that wonderful day I moved here more than two decades ago, I wish I had understood how complicated the country below me really was. Understanding Italys geographical location on the map is the key to deciphering its many challenges. The country, though one of the founding cornerstones of Europe, is as close to North Africa and the Middle East as it is to countries like Germany. South across the Mediterranean Sea from Rome is Sicily, whose western islands of Lampedusa and Linosa could have easily been a territory of North Africa, just seventy miles from Tunisia and a few hundred from Libya. Its little wonder the United States and NATO keep their strategic drone command center and Middle East and Africa surveillance hubs at the Sigonella base on the island. To the east, on the other side of Italys boot, are the Balkans, Greece and Turkey, all just a ferry ride away.

When I first moved to Italy, several people told me that Africa begins in Rome, which was something I didnt understand at the time, but certainly do now. The type of poverty that permeates much of Africa exists in parts of the Italian south as well. Almost two million Italian children live below the poverty line in the regions that start just a few kilometers south of the capital. UNICEF, the United Nations Childrens Fund, says Italy has the highest overall percentage of people living in extreme poverty anywhere in Europe, primarily due to the mismanagement of resources and funds intended for its own people. With that in mind, its little surprise that leaders pay even less attention to vulnerable strangers.

Italys major problems lie in its southern regions, known as the Mezzogiorno (literally midday), which holds a third of the countrys population and all its organized crime hubs. Unemployment is highest here, hovering around forty percent in some areas, and so is the murder rate, which regularly tops ten murders a month in Naples, a city of just three million people. Puglia, the heel of Italys boot, was the central entrance point for counterfeit cigarette and arms trafficking in the 1990s, during the height of the Balkan conflicts just a few miles across the Adriatic Sea. Basilicata and Calabria, which make up the boots insole, still have villages without internet or schools. Moving north towards Rome through Campania, from the toe of the boot, the Amalfi Coast is the sparkling diamond among a region that is easily the most lawless and dangerous in the country, made famous by Roberto Savianos tales of death and despair in his bestselling book Gomorrah , all just a few hours drive from Rome.

This southern Italy is not the stuff of guidebooks and postcards. Its ports, as beautiful as they may be over a cocktail at sunset, hide unparalleled criminal activity as everything from deadly arms to stolen antiquities find their way past the often-corrupted customs officials.

Lately, however, Italys southern ports have become the gateway for a very different type of cargo, with hundreds of thousands of migrants and refugees arriving each year. I started covering the migrant crisis in 2009, when the blue wooden fishing boats bought from scrap yards by enterprising smugglers started washing up on the shores of Lampedusa, filled with economic migrants and those fleeing famine and dirty wars in Africa. In the beginning, the smugglers would even navigate the old fishing boats themselves and then either escape on smaller speed boats that trailed them or wait until they got caught and were deported back to Tunisia or Morocco and do it all over again. Some of those old blue boats can still be seen, washed up on Lampedusas coastline, but most have been hauled to the center of the island where they are piled high in what amounts to a gigantic boat cemetery.

It must be noted that the migrant crisis that impacts Italy is a very different one from that involving Syrian refugees in the rest of Europe. Italys crisis started as a trickle of people coming from across the sea in North Africa to the Sicilian island of Lampedusa more than three decades ago. Arrival numbers rarely topped a few thousand a year. It picked up speed in the years before the Arab Spring, when mostly young men started arriving, but the uprisings that began in late 2010 marked a great change in number of arrivals, which suddenly started topping fifty thousand or more. This also led to a rise in human smugglers, who soon understood that the more desperate people were, the more they would pay for passage across the sea. When the Arab Spring exodus calmed down, the smugglers werent ready to give up their profits and soon started actively searching out sub-Saharan African economic migrants and refugees fleeing war and persecution who wanted to take a chance on a better life in Europe, which seemed like a magical land of hopes and dreams until they realized that the opportunities werent meant for them. It didnt take long for sex traffickers to realize they could use the established smuggling routes to ferry exploited women to Italy.

Next page