THE VOYAGEUR

THE VOYAGEUR

BY

GRACE LEE NUTE

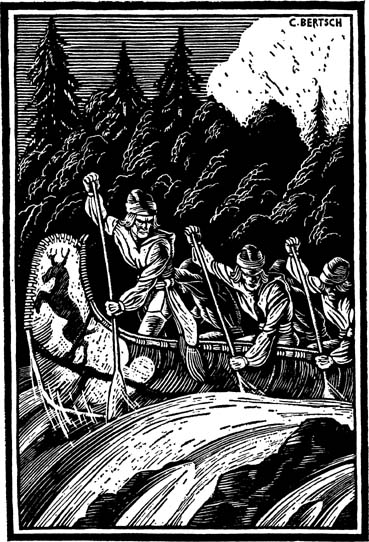

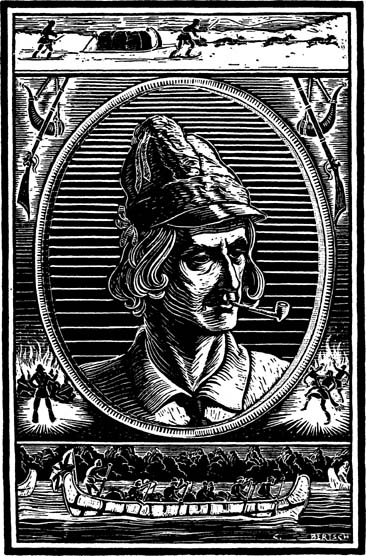

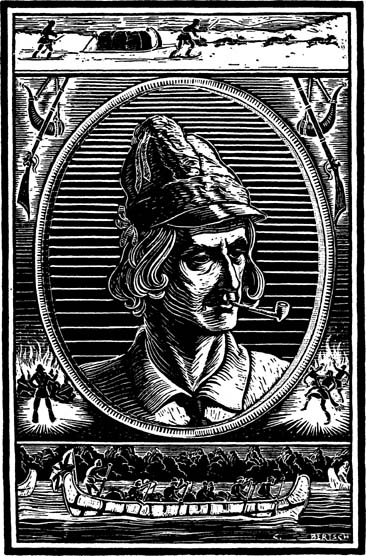

Illustrations by

Carl W. Bertsch

MINNESOTA HISTORICAL SOCIETY PRESS

First published in 1931 by D. Appleton and Company

Reprinted in 1955 by the Minnesota Historical Society

First paperback printing, 1987, by the Minnesota Historical Society

www.mnhs.org/mhspress

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National

Standard for Information Sciences-Permanence for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481984.

International Standard Book Number 0-87351-213-8

E-book ISBN: 978-0-87351-706-5

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Nute, Grace Lee, 1895-1990

The voyageur.

Reprint. Originally published: New York: D. Appleton, c1931.

Bibliography: p.

Includes index.

1. French-Canadians. 2. Fur tradeCanada. 3. CanadaSocial life and customs. I. Title.

F1027.N96 1986

971.004114 8628468

TO

HELEN BIGELOW MERRIMAN

SAID ONE OF THESE MEN, LONG PAST SEVENTY YEARS OF AGE: I COULD CARRY, PADDLE, WALK AND SING WITH ANY MAN I EVER SAW. I HAVE BEEN TWENTY-FOUR YEARS A CANOE MAN, AND FORTY-ONE YEARS IN SERVICE; NO PORTAGE WAS EVER TOO LONG FOR ME. FIFTY SONGS COULD I SING. I HAVE SAVED THE LIVES OF TEN VOYAGEURS. HAVE HAD TWELVE WIVES AND SIX RUNNING DOGS. I SPENT ALL MY MONEY IN PLEASURE. WERE I YOUNG AGAIN, I SHOULD SPEND MY LIFE THE SAME WAY OVER. THERE IS NO LIFE SO HAPPY AS A VOYAGEURS LIFE!

PREFACE

It is time to write the story of the voyageur. His canoe has long since vanished from the northern waters; his red cap is seen no more, a bright spot against the blue of Lake Superior; his sprightly French conversation, punctuated with inimitable gesture, his exaggerated courtesy, his incurable romanticism, his songs, and his superstitions are gone.

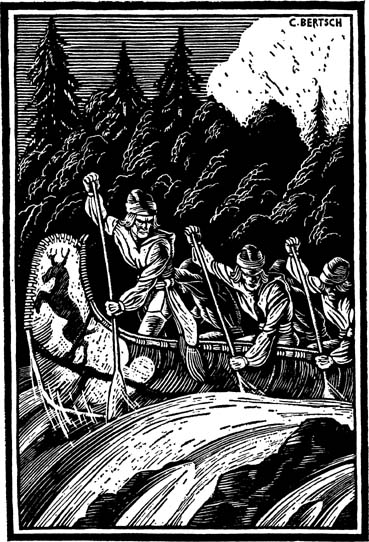

In certain old books and in many unpublished manuscripts, however, he still lives. Read the diaries of Montreal fur-traders and the books of travelers on the St. Lawrence, the Saskatchewan, and the Great Lakes in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. From their pages peals the laughter of a gay-hearted, irrepressible race; over night waters floats the plaintive song of canoeman, swelled periodically in the chorus by the voices of his lusty mates; portage path and campfire, foaming rapids and placid fir-fringed lake, shallow winding stream and broad expanse of inland sea, whitewalled cottage of Quebec hamlet and frowning pickets of Northwest postbecome once more the voyageurs habitat; the French rgime comes to its tragic close on the Plains of Abraham; the British rule lasts but a brief half-century in a large portion of the fur country; Washington supersedes London in the allegiance of many of the red children of the far western watersstill the voyageur places his wooden crosses by dangerous sault and treacherous eddy, sings of love in sunny Provence, and claims his dram on New Years morning, undisturbed by wars, treaties, and the running of invisible boundary lines.

Though he is one of the most colorful figures in the history of a great continent, the voyageur remains unknown to all but a few. This little book seeks to do justice to his memory for the romance and color he has lent to American and Canadian history, and for the services he rendered in the exploration of the West.

My thanks are hereby offered to the many persons who have given me assistance and encouragement in the preparation of this study. I am especially indebted to several members of the staff of the Minnesota Historical Society, who have called my attention to data relating to the voyageurs; and to my sister, Virginia Beveridge, who typed the manuscript for me. Mr. Marius Barbeau, of the National Museum, Ottawa, has been both generous and very helpful in supplying me with the airs and words of La belle Lisette and Voici le printemps, as well as with some material that does not appear in this volume. To Mr. J. Murray Gibbon I also wish to extend my thanks for his generosity in translating several songs especially for this volume. I am also grateful to Miss Constance A. Hamilton for permission to use her translation of Voici le printemps, and to Mrs. William H. Drummond for permission to use her late husbands poem, The Voyageur.

G. L. N.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER

I

FURS AND FUR-TRADERS

I

T HE term voyageur, a French word meaning traveler, was applied originally in Canadian history to all explorers, fur-traders, and travelers. It came in time to be restricted to the men who operated the canoes and batteaux of fur-traders, and who, if serving at all as traders, labored as subordinates to a clerk or proprietor. Even as late as 1807, however, the famous Beaver Club of Montreal, a group of prominent and, usually, successful fur-merchants or traders, balloted to determine whether its name should be changed to the Voyageur Club. Thus the term was somewhat vague, though always referring to men who had had actual experience in the fur trade among the Indians. In this book the term is restricted to French-Canadian canoemen.

The French rgime was responsible for the rise of this unique group of men. From the days of earliest exploration until 1763 a large part of what is now Canada and much of the rest of the continent west of the Appalachian Mountains was French territory. In this vast region lived the several tribes of Indians with whom the French settlers about Quebec and Montreal were not slow to barter furs. Beaver, marten, fox, lynx, bear, otter, wolf, muskrat, and many other furs were obtained. Furs were in great demand in Europe and Asia, and both the English colonists along the Atlantic seaboard and the French in New France supported themselves in large part by means of a very flourishing fur trade.

At first the Indians took their skins and furs down the St. Lawrence to Quebec and Montreal, whither annual fairs attracted them; but in the process of time ambitious traders intercepted the natives and purchased their furs in the interior, thus gaining an advantage over fellow traders. The enmity between the Iroquois and the Algonquin also tended to prevent the Indians from making their annual trips to the lower St. Lawrence, since the western tribes, who brought most of the furs, feared to pass down the river through enemy territory.

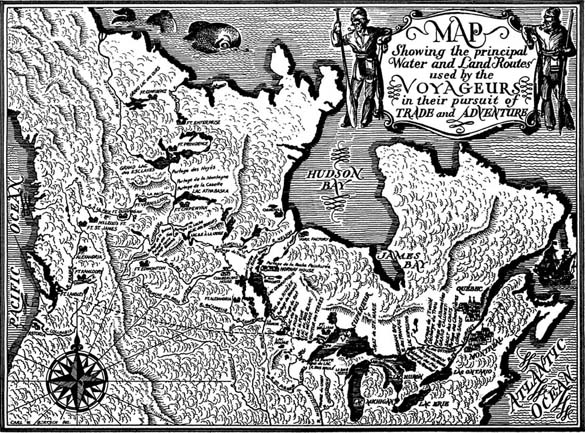

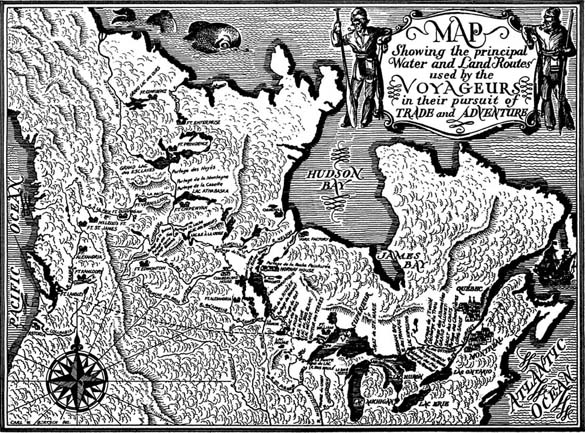

When traders began to enter the Indian country, the voyageur may be said to have been born. Farther and farther up the St. Lawrence, up the Ottawa River, into lakes Huron and Michigan, the traders ventured. Erie and Ontario were explored, and finally Lake Superior. From these lakes more venturesome traders entered the rivers emptying into them and reached the Ohio and Illinois countries and the region about the Mississippi. They even found the rivers emptying into Lake Superior from the west and marked out the route by way of Rainy Lake into Lake Winnipeg. When Canada was lost to the English in 1763, French posts were established far up the Saskatchewan, and French traders had seen the Rocky Mountains and knew of the Oregon River. On these trips westward the birch-bark canoe was almost the sole vehicle of transportation, and men from the hamlets on the lower St. Lawrence were the canoemen.