The Fox in Nature

The modern scientific names of the fox distinguishing 21 species and 8 genera depend on classical terms that refer to it as incomplete, false or ambiguous or simply a bad creature. The South American small-eared fox, for example, bears the Greek tag Atelocynus microtis, which translates roughly as incomplete dog with small ears, and the culpeo whose common name denotes its culpability was once classified in the genus Dusicyon, which means something like a dog of bad character, but is now said to belong to the genus Pseudalopex, or false fox. These aspersive classifications are caused, I think, by the foxs tendency to disrupt otherwise neat arrangements by its refusal to participate in a systematic account of nature, but also by an ancient tradition that considers the fox a wicked creature. The fox seems to be as open for study as any animal, but it is notorious for turning up where it had not been expected or where it should not be and for changing its defining qualities to adapt and take advantage of different situations. As common as the fox is throughout the world, it has mostly eluded scientific certainty, and the efforts of naturalists to rein in this ubiquitous yet elusive creature reveal the biases governing their attempts to define nature itself, which is equally elusive. Ultimately, to trace the ways that naturalists have defined the fox over the centuries is to glimpse the principles governing different definitions of nature. The first Westerner to attempt a systematic account of nature was Aristotle, whose explanations may seem wholly unscientific today, founded as they are on beliefs that he took as truths but that have long been discounted. Nonetheless, his influence lies in the systematic approach he brought to classifying animals.

Aristotle follows three principles to classify animals: the different substances that make up analogous body parts; the different environments that animals inhabit land, sea or air which correspond directly to the substances of which their bodies are made; and the differences in their dispositions revealed through their interactions with other animals. Although Aristotle does not devote much space to foxes, he refers to them significantly in the explanations of his systematic classification, making them serve the ironically exemplary role of antipode to humans.

In the Aristotelian hierarchy, humans are closest to divinity, which is the pure life of light and air, and while humans do not quite attain divine purity, they do possess a fluid warmth. In Aristotles scheme, the warm and fluid materials include blood, lard, semen and flesh. At the opposite end of the spectrum are the materials close to the cold, dark and hard earth, such as sinew, hair, bone, gristle and horn.

In comparing body parts, Aristotle lays special emphasis on the genitals, because, in serving the function of generation, they most contain the nature of the individuals power of life. Thus his alignment of penises: The male organ shows much diversity. In some it consists of gristle and flesh, as in man; and the fleshy part does not become inflated, while the gristly part becomes The three types of penises, those of men, ungulates and predators, are ranked according to what Aristotle believes they are made of. Since he sees the male human being as the complete form of animal life, foxes, in regard to their penises, stand two removes from the human and from completeness. A humans penis is made of gristle and flesh, while an ungulates is sinewy. Gristle and sinew are both earthy substances, so the significant difference here is that the human penis also contains flesh. Fox penises supposedly have neither flesh nor gristle-sinew, but are simply bone and therefore earthier, colder and less perfect than the penises of ungulates and humans.

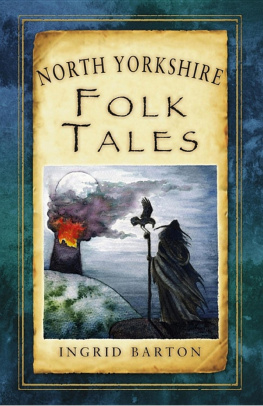

| An Arctic fox cub in its den. Aristotle believed foxes to be colder and less complete than other animals because they burrow in the earth. |

The cooler and incomplete nature of the fox gains further elucidation when Aristotle describes the different modes of reproduction: The fox mounts the vixen for intercourse, and she brings forth as the bear does: the young are even more unarticulated... When the young have been born, by licking them Concocting in Aristotelean biology means completing the animal into its full form. This process, by no surprise, occurs through heat, so that, in licking her babies, the vixen warms them, shaping them towards the complete form, which is to be found in adult malehood. Foxes have a cooler, bonier physiology that is closer to the earth than that of humans, and so must be licked into shape.