Also by

ROBERT D. RICHARDSON

Literature and Film (1969)

The Rise of Modern Mythology (with Burton Feldman) (1972)

Myth and Literature in the American Renaissance (1978)

Henry Thoreau: A Life of the Mind (1986)

Ralph Waldo Emerson Selected Essays, Lectures and Poems (1990) (editor)

Emerson: The Mind on Fire (1995)

Three Centuries of American Poetry (1999) (coeditor, with Allen Mandelbaum)

William James: In the Maelstrom of American Modernism (2006)

First We Read, Then We Write: Emerson on the Creative Process (2009)

The Heart of William James (2010) (editor)

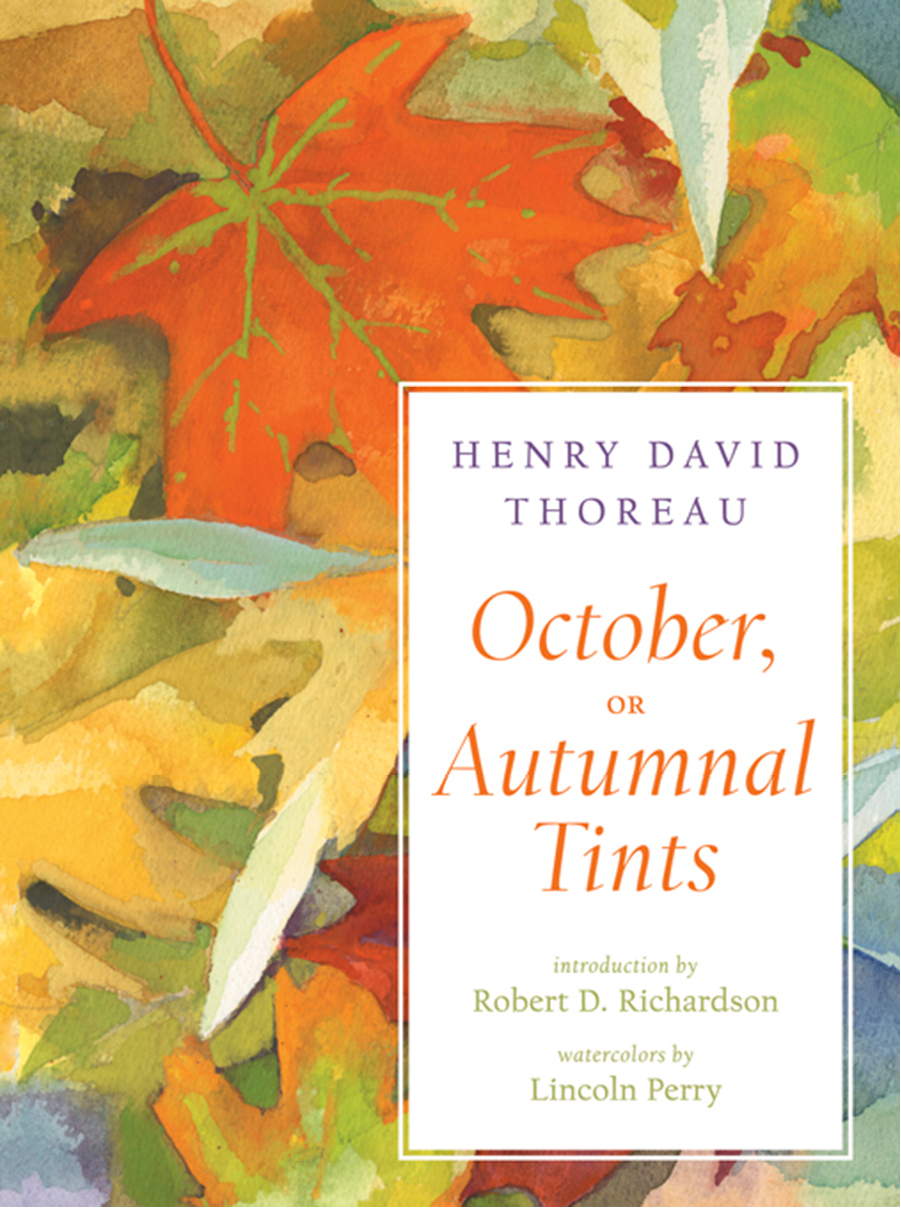

HENRY DAVID THOREAU

Introduction by Robert D. Richardson

Watercolors by Lincoln Perry

W. W. Norton & Company

NEW YORK LONDON

For Annie and Ann

Contents

Foreword

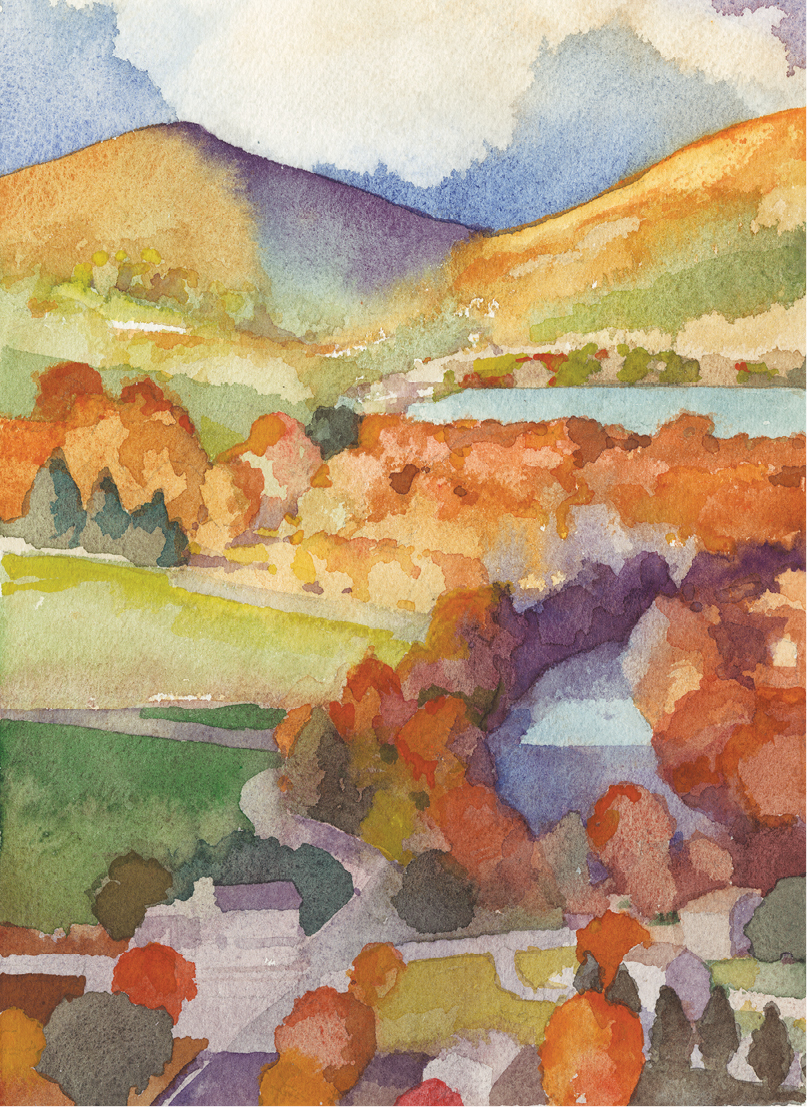

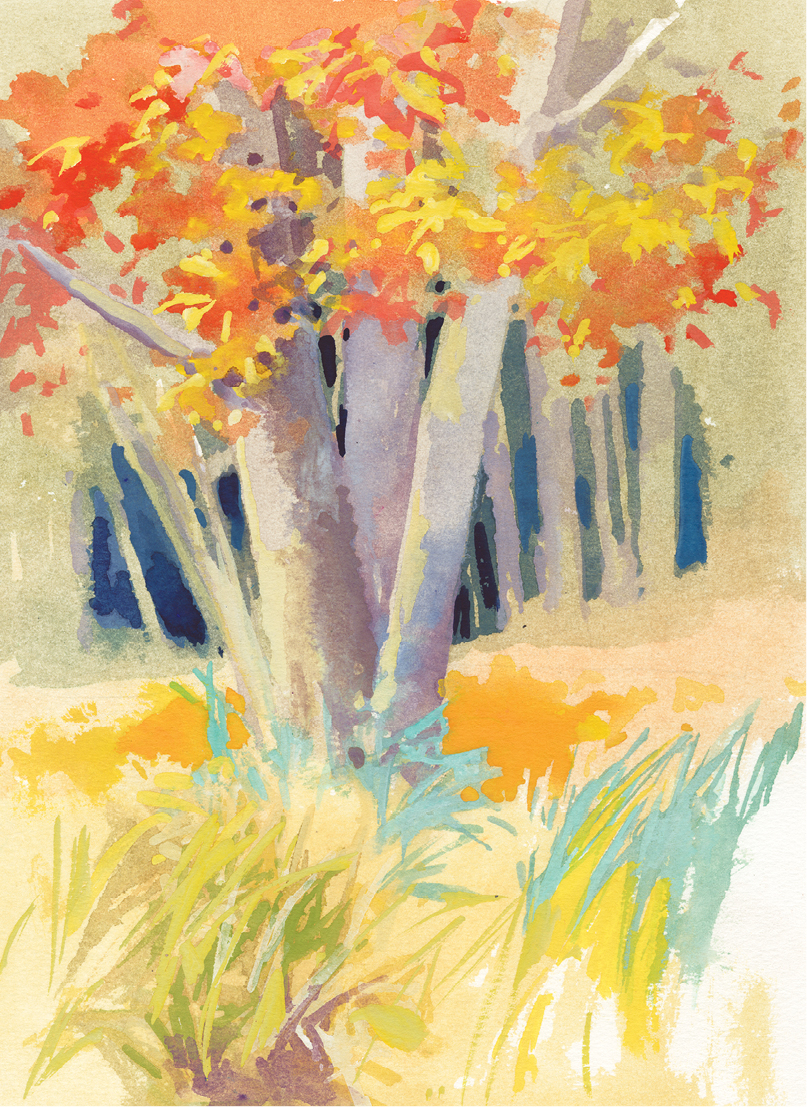

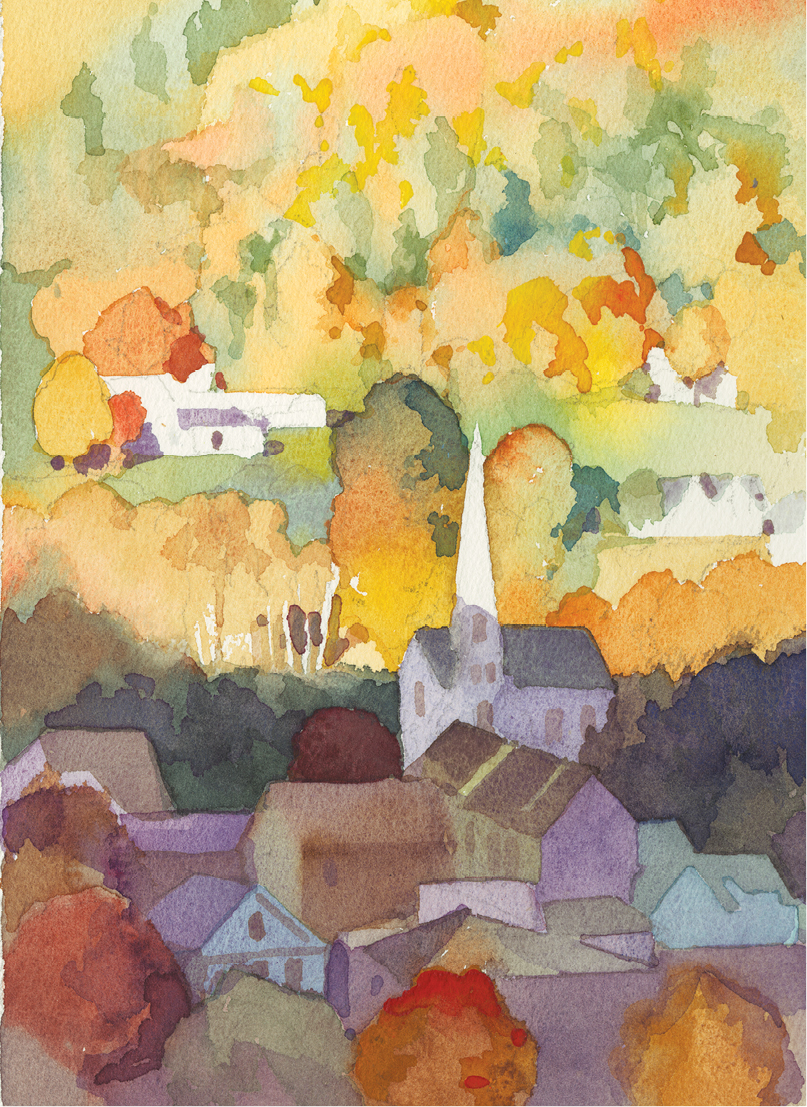

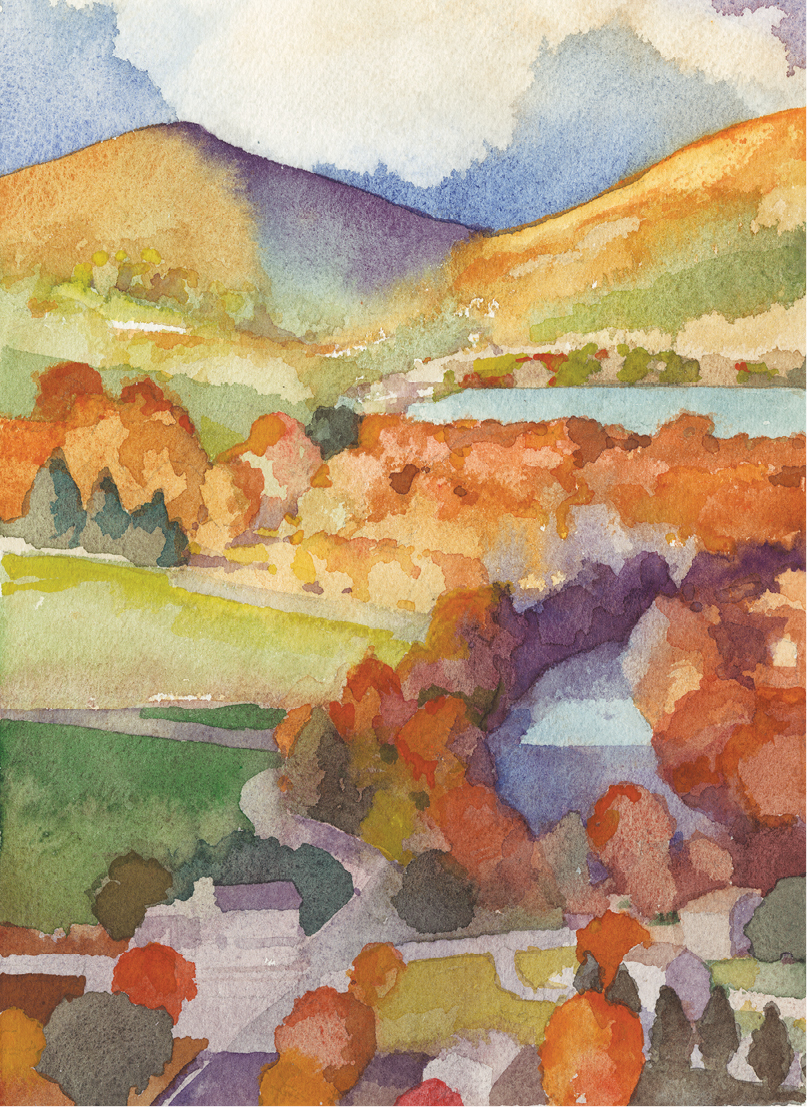

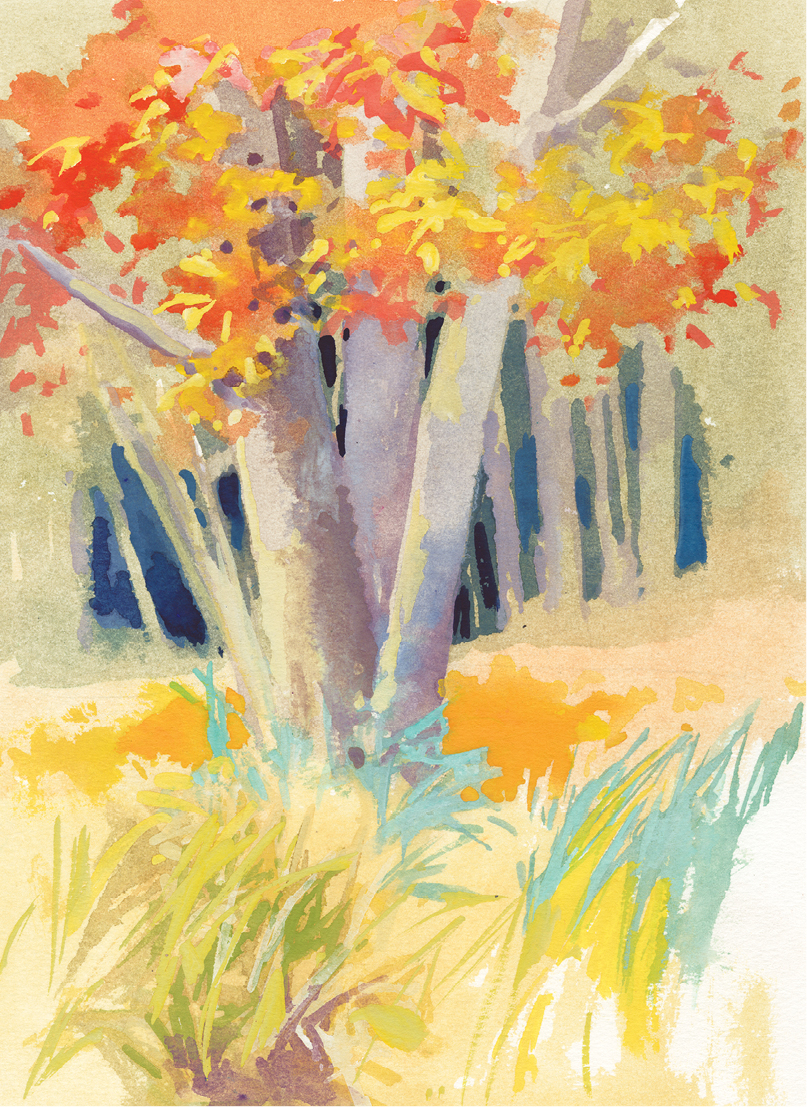

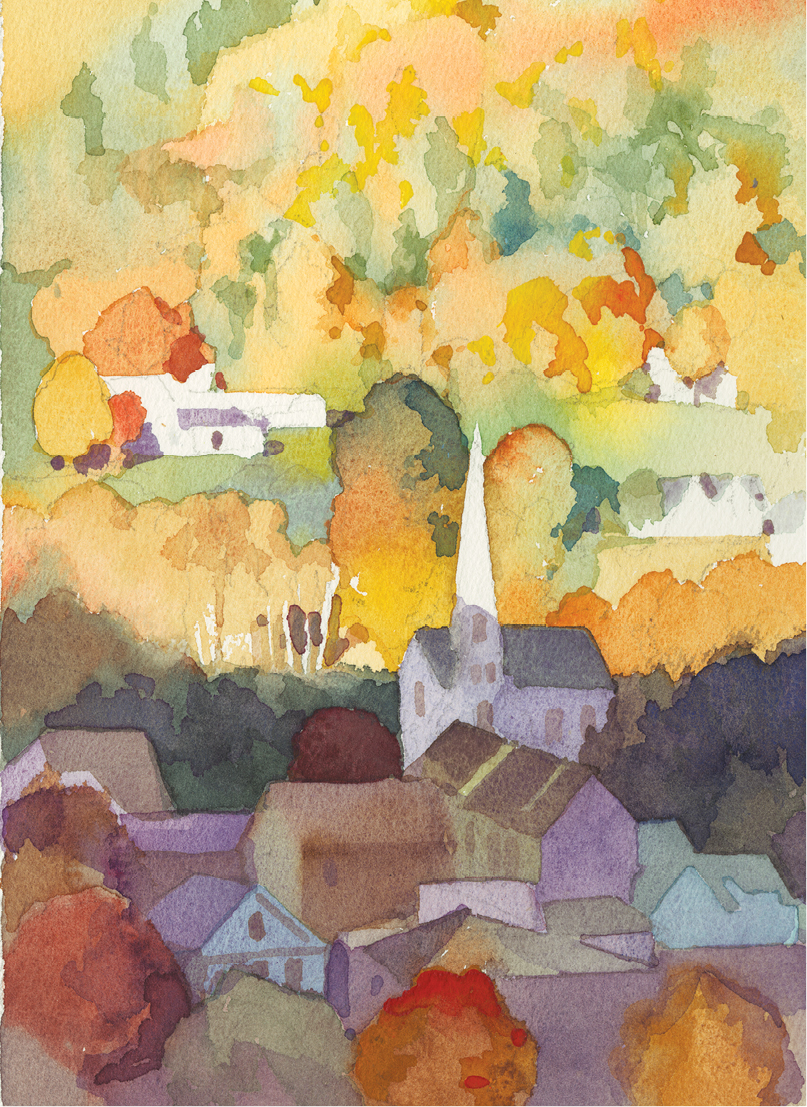

This volume has three parts. One part is Henry Thoreaus classic essay, or excursion, Autumnal Tints, written as he lay dying. A second part is the suite of watercolors by the contemporary artist Lincoln Perry, watercolors on one of Thoreaus great themes, the glorious color of autumn seen through an insistence that surely joy is the condition of life. The third part is a biographical and critical sketch of Thoreaus engagement with autumn and his coming to see it as a time, not of death and decay, but of ripeness, harvest, and new life springing from old.

What unites these three parts is their common aim to make you, the reader and observer, see; but each part stands alone in some ways. No one can beat Thoreau at what he does best, and no one need try. The biographical/critical essay sees Thoreaus essay as a hymn and a guide to victory, as a triumphant testament to how vision rises into the visionary. The watercolors are not attempts at botanically exact illustrations of Thoreaus text but something else. Botanical drawings may help one identify a leaf or a treeand we have field guides for thatbut even the best botanical drawings are Platonic types, typical leaves and trees, never a particular leaf or tree. Lincoln Perrys watercolors present and celebrate particular leaves, trees, and landscapes while he makes us see more than we usually do in the folds and colors and shadows of a particular leaf or the way one tree seems to give out light while another seems to draw down light into its darker self. We hope that the reader and observer can make from the three parts of this book a fourth, and his own, viewor perhaps even a visionof fall color.

ROBERT D. RICHARDSON

The Last Leaves of

Henry Thoreau

Henry Thoreau

I. DEATH IS THE MOTHER OF BEAUTY

In February 1862, as the forty-four-year-old Henry Thoreau lay dying in his family home on Main Street in Concord, Massachusetts, in the cold New England winter, he roused himself to one last great literary effort. He knew he had not much longer to live, and the knowledge tightened his grip on the present. When his friend Harrison Blake asked him how the future seemed to him, Thoreau replied, Just as uninteresting as ever. His friend Emerson maintained that there is no release in all the worlds of God except performance. Thoreau also understood that no excuses would suffice for nonperformance. Certainly dying young could be no excuse. As recently as 1859 he had written in his journal:

I have many affairs to attend to, and feel hurried these days.... It is not by a compromise, it is not by a timid and feeble repentance, that a man will save his soul, and live at last. He has got to conquer a clear field, letting Repentance and Co. go. Thats a well-meaning but weak firm that has assumed the debts of an old and worthless one. You are to fight in a field where no allowances will be made, no courteous bowing to one-handed knights. You are expected to do your duty, not in spite of everything but one , but in spite of everything.

Emerson had also said, sternly perhaps but also comfortingly in Self-Reliance, Do your work and I shall know you.

With flinty resolve, Thoreau now turned away from the grand visionary projects he had been nursing of late, abandoning the huge Calendar of Concord that he meant to build up season by season, tree by tree, bird by bird, day by day, and detail by detail until it would flower into completion as an inexhaustible account of every natural happening in a statistically average year as lived out at the center of Thoreaus universe, Concord, Massachusetts. Thoreau now turned from this no longer realizable ambition to smaller projects he could still get both his hands around, stand-alone bits and pieces of the grand project. One of the chief of these was an account of the spectacular fall color in New England that he intended to call October, or Autumnal Tints, and which belonged to a larger never-to-be-realized project he called The Fall of the Leaf.

II. THE LAW OF DEATH IS THE LAW OF NEW LIFE

A common view of autumn, then and now, is that autumn is the time of dying and decay, the season of endings. We do not expect a September Song to be a merry one. Emersons aunt Mary, a strict and brilliant Calvinist, accounted for fall color by insisting it is the angel of consumption [tuberculosis] that dyes the cheek of fading Nature with such hectic bloom.

But the paradoxical, counterintuitive idea that drives Autumnal Tints, the idea that death is not annihilation and something to be feared but rather a necessary stage in the continuing cycle of nature, and thus something to be welcomed as much as any other aspect of nature, is quintessential Thoreau. The idea pops up on the first page of the journal he began in 1837, and by 1862 his conviction that the passing away of one life is the making room for another had been for twenty-five years a constant element of Thoreaus hot central core, the set of beliefs on which he habitually acted. This way of understanding death was first tested in Thoreaus own experience during the eighteen months from July 1840 to January 1842, which was easily the most emotionally tumultuous stretch of Thoreaus own life.

In July 1840, Henrys older brother John proposed marriage during a walk on the seashore with eighteen-year-old Ellen Sewall, the spirited, pretty girl from Scituate, Massachusetts, they were both in love with. That same month saw twenty-two-year-old Henrys first publicationsa poem (Sympathy) and a prose piece (Aulus Persius Flaccus)both in The Dial , the new transcendentalist magazine edited by Margaret Fuller. Ellen impulsively accepted twenty-four-year-old John, but she soon realizedshe saidthat it was Henry she really cared for, and that fact plus family pressure obliged her to quickly reverse herself and turn down John. Ellens family sent her off to Watertown, New York, to get her away from the Thoreau boys. But then, in November, an undeterred Henry proposed to her by letter. This time Ellen consulted her father first and, at his prompting, turned down Henry. Ellens father, Edmund Quincy Sewall, was an old-line conservative Unitarian clergyman who was actively opposed to the radicalism of Emerson and his friends, including, of course, both Thoreau boys. Emerson thought and said that the meaning of the life of Jesus is that all men and women have the potential for divinity within them; Thoreau already believed something very similar.

Next page

Henry Thoreau

Henry Thoreau