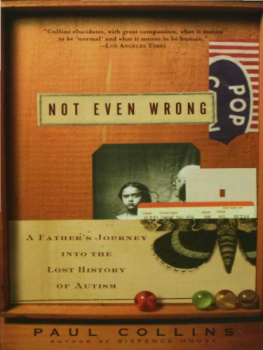

NOT EVEN WRONG

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

Banvard's Folly

Sixpence House

NOT EVEN WRONG

A Father's Journey into

the Lost History of Autism

PAUL COLLINS

Copyright 2004 by Paul Collins

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. For information address Bloomsbury Publishing, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010.

Published by Bloomsbury Publishing, New York and London Distributed to the trade by Holtzbrinck Publishers

All papers used by Bloomsbury Publishing are natural, recyclable products made from wood grown in sustainable, well-managed forests. The manufacturing processes conform to the environmental regulations of the country of origin.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the hardcover edition as follows:

Collins, Paul, 1969

Not even wrong : adventures in autism / Paul Collins.First U.S. edition.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

eISBN 978-1-59691-749-1

1. Autism in children. 2. Autism in childrenPatientsRehabilitation. 3. Caregivers.

I. Title.

RJ506.A9C645 2004

618.92'85882dc22

2003017574

First published in the United States by Bloomsbury Publishing in 2004

This paperback edition published in 2005

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Typeset by Hewer Text Ltd, Edinburgh

Printed in the United States of America

by Quebecor World Fairfield

CONTENTS

For Morgan

CHAPTER 1

A collapsible steamer basket, opened to its full circumference, resembles a giant perforated metal flowerlike something the Iron Giant might wear in his lapel. I never gave it any thought before becoming a parent. But a child forces you to retrace the steps of things that you've forgotten you ever learned, like how to turn a doorknob, how to wash your hands, or how to stare so intently at a kitchen implement that it becomes a completely abstract object.

"Da-ya dicky-doe," Morgan reports, and clatters it aside before racing off to the other end of the house. I look at Jennifer, she looks at me: we shrug. He's two going on three, and he has his own language.

Most days Jennifer has the overnight and the early morning Morgan shift. I have the morning and the evening. The afternoons we usually have off. I clomp upstairs to muse over bound Victorian volumes of Notes and Queries, peruse the London papers on-line, rearrange my pens, examine my shoelaces. Sometimes, unbelievably, I write. Jennifer goes into a bedroom scattered over with crossword puzzles, slathered paint palettes, and crunched-out tubes of Winsor & Newton acrylic and emerges with a spiral-bound notebook, headed for her favorite writing table at the local bagel shop. During these afternoonsthe closest thing we have to a workdayour son is with Marc, an old friend of ours who has basically become his nanny. But today Morgan's spending the afternoon with us instead.

We follow Morgan to our bedroom, where he is paging through a weighty Merck Manual that he's pulled off our bookshelf. He is on cardiovascular disorders, in the early part of the book. He grabs my finger like a pointer, jabbing it at words.

"A... doctor... may... suspect... uh, endocarditis..."

He jams my finger harder into the word, demanding explanation.

"Morgan, that's... oh, that's a hard word."

He pushes my finger away, done with me, and returns to turning pages. He hasn't made it past lymphatic disorders in the manual, which is probably just as well, because the later bits on occupational lung diseases really aren't good reading for children.

"Hey, Morgan," Jennifer says. "Hey, Morgan."

He turns the page.

"Hey, Morgan. We're going to ride in a taxi today. A yellow taxi. All of us. In a yellow taxi."

"Naya," he repeats. This is his word for yellow. "Naya taxi."

"That's right. You're going to ride in a yellow taxi! With Mommy! And Daddy!"

He doesn't look up from the pages, but he has the faintest hint of a smile in his face, undetectable to anyone else.

"Morgan... " I sing. "Mooo-rgan..."

He turns the page, looking even more intent, ignoring me.

"Morr-gan. I know you. I know you. I know you're listening."

No.

"Mor-gan. Morrr... gotcha gotcha gotcha!"

I pounce on him, and he collapses against me in hysterical giggling. It's been the best joke for as long as he can remember.

"Careful, honey bunny." He's tugging at the coiled black wire to the doctor's ear-probe light hanging on the wall. "Gentle. We can't break that."

We can, of course, and probably will.

"Gentle. Gentle!"

I root through the supply of toys in Jennifer's messenger bag, the multitudes of card decks, writing materials, and books to keep Morgan occupied while we wait in the doctor's office. Out comes a thin blue hardcover book.

"Cat!" Morgan says firmly. "Hat!"

And then he immediately turns his attention back to the coil. The door opens; Jennifer and I both look up.

"Hi. I'm Dr. Whalen."

"I'm Jennifer." My wife shakes her hand.

"I'm Paul. And this is Morgan."

"Hello. Hi, Morgan."

Morgan is still busy inspecting the coil, thrumming it back and forth.

"So..." The doctor looks at him quizzically over her clipboard. "Three-year checkup?"

"We're a little early for that, actually," Jennifer admits.

"We just moved here," I explain. "It's been a little while since his last checkup, so we just figured..."

I trail off. There's not much else to say, since there's nothing actually wrong with him.

"Okay," says the doctor. She gives us the standard questions: are his vaccinations up-to-date, has he been ill lately, and so forth, all while examining his muscular little body. Morgan ignores her. He's studying the buttons on my shirt. She does the usual prodding and poking, and Morgan swats away the lighted ear probe, as any sensible child would.

"How's his hearing?" she asks.

"He can hear me unwrap a Popsicle from across the house."

"Mmm-hmm."

She sets down her clipboard. "Have you had Morgan tested for developmental delays?"

Jennifer and I stare at her blankly.

"What?"

"Your child hasn't said a word in the last five minutes. And"she retraces her steps through the room"he didn't look up when I entered, or when I said his name. Or when I shook a toy."

She rattles a rather unimpressive trinket.

"He's a very secure child," I explain. "He doesn't care about you. No offense."

"Morgan," says the doctor, "would you like a sticker?"

She holds up a grim little decal of a teddy bear for several seconds before giving up.

"He didn't even look," she says.

I didn't even look.

"He's like that," Jennifer says. "If he's focused on something, it doesn't matter what you have, and it doesn't matter who comes into a room. He interacts, but only when he feels like it."

"It's not a typical response for his age," the doctor insists. "And he doesn't use language with you, either."

"He does... well, what I mean is, he's fascinated by language. He learned his alphabet when he was one."

"Really?"

"Yeah. He reads words now, sentences."

Jennifer pulls out the Magna Doodle, a sort of writable Etch A Sketch that Morgan makes us take everywhere.

"Look," Jennifer says, as much to the doctor as to Morgan. She draws a bunch of rounded fruit and stem and then writes " G R A P E S" underneath.

"Gwayps!" Morgan yells.

Then Jennifer writes "D I A M O N D." Before she's even drawn the picture:

Next page