THE LOST WORLD OF JAMES SMITHSON

Science, Revolution, and the Birth of the Smithsonian

Heather Ewing

BLOOMSBURY

CONTENTS

for Chico

and

to the memory of Gene R. White

in token of gratitude

"Has Mr. what's his Name? been with you at Money hill? Mr Macie or Masy, originally written (I suspect) Mazya noun adjective from the Verb to amaze or make wonder!"

Dr. William Drew to Lady Webster, 1797

PROLOGUE

1865

The best blood of England runs through my veins. On my father's side I am a Northumberland, on my mother's I am related to kings, but this avails me not; my name will live on in the memory of men when the titles of the Northumberlands and Percys are extinct or forgotten.

James Smithson, undated

THE MORNING OF January 24, 1865, dawned bitterly cold in Washington. Nearly four years into the Civil War, the nation's capitalencircled with forts and filled with makeshift hospitalswas also battling a brutal winter. Business in the stores and counting rooms of Georgetown had come to a virtual standstill, customers unable to navigate roads buried in a deep frozen slush. The Potomac River bristled with ice, wreaking havoc with the transport steamers and delaying the mail boats. Near Indian Head a steamer carrying a load of mules sank after being cut through; by Jones Lighthouse the steamer Sewanee had run aground, the tugs unable to rescue her; and down at the city wharf the U.S. Transport Manhattan lay taking water, badly damaged after its tussle with the river. At the new Smithsonian Institution, the water kept in buckets and barrels throughout the building as a precaution against fire was frozen solid.

The crisp turreted silhouette of the Smithsonian's red sandstone castle had formed a part of Washington's cityscape for scarcely a decade in 1865. Sitting alone in the marshy bottomlands of the monument grounds, halfway between the Capitol and the forlorn stump of the unfinished Washington Monument, the Smithsonian was nevertheless rapidly becoming the pride of the cityand well on its way, too, to becoming a showcase of the nation. Since its founding it had quickly assumed a leading role in America's fledgling scientific community. Its scientists, fitted out with instruments and collecting instructions, were attached to government surveys and expeditions, and the specimens they amassed made their way by the thousands back to Washington. Already the museum was hailed as the "most complete of any in existence in several branches of the natural history of North America." A steady stream of publications issued from the institution, including the aptly titled Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge. These journals began to fill the shelves of the academies of Europe, and the Smithsonian, as host of the government collections and promoter of knowledge, became the voice of a new nation's progress, rapidly raising the profile of American science.

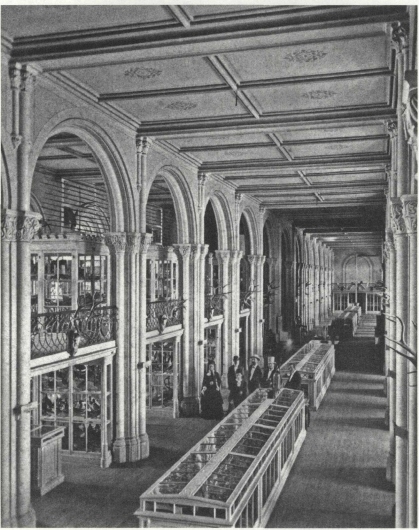

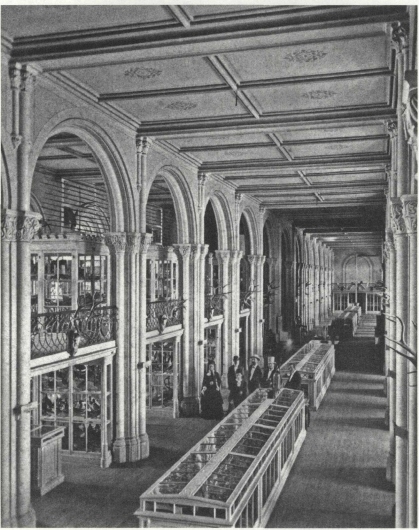

On this grey January day the Smithsonian, despite the cold, was alive with activity. Secretary Joseph Henry, the head of the institution and the man who had ordered the buckets of water stationed throughout the building, sat in his office dictating to his chief clerk the voluminous annual report of the institution. It was due at the printers in a week's time. His family, assailed more than occasionally by the stench of drying animal skins from the adjacent museum offices, were at home in their quarters in the east wing. The young bachelor naturalists who lived in the towers that rose over Henry's office were employed in the museum, packing specimens on the balconies overlooking the building's cavernous central hall. The lowvaulted basement, too, was humming with workmen wheeling out ashes and refuse and others busily crating the institution's publications for distribution.

The great hall of the Smithsonian building, with the museum collections, c. 1867.

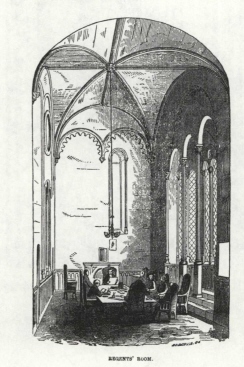

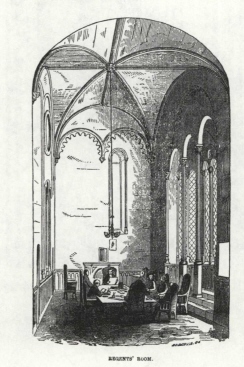

A number of visitors had appeared that morning to see the new building. On the ground floor they admired the towering gothic cases of the museum, and they perused the contents of the chapel-like library. Upstairs they were shown the lecture hall, one of the finest in the country. A few even made the chilly climb to see the view from the top of the tall north tower, where President Lincoln had come earlier in the war to study the Confederate troops massing in Virginia. They also peeked into the regents' room, one of the most elegant spaces in the building. It was here that the institution's impressive governing board, consisting of the Vice President of the

The regents' room, where the Smithsonian's governing board met and where James Smithson's effects were kept.

United States, the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, the mayor of Washington, six members of Congress and six appointed citizens, convened, sitting in muscular throne-like chairs under the soaring ribs of the gothic ceiling.

In the picture gallery two workmen were arranging the collection of Indian paintings by John Mix Stanley. At the beginning of the week, to brace themselves against the cold, the two men had brought a stove from the apparatus room at the other side of the lecture hall. All week the stove labored to keep the chill from the room as the men hung the paintings. The room was an immensely tall one, and the cold pushed across it between the enormous mullioned round-arched windows. Displayed on a pedestal in the center of the room was one lone statue, far from its classical siblings in the sculpture gallery downstairs. It was a marble copy of the antique figure The Dying Gaulplaced, apparently, to encourage visitors to draw an analogy between an ancient vanquished people and these "noble savages" now being extinguished across the West.

Secretary Joseph Henry's office sat behind the great rose window between the two front towers of the building, on the third floor. A garrulous visitor had just settled down on the couch when a sharp crackling sound overhead startled them all. The chief clerk William Jones Rheesthe man who would pen the first biography of James Smithsonimagined it was simply a giant piece of ice sliding off the roof, but as the noise continued and grew louder, the men rushed to the door overlooking the lecture hall. All was gloomy and dark. Dense clouds of smoke billowing over the building could be seen through the oculus in the ceiling. "The house is on fire! Sound the alarm!" Henry cried, as he ran off down the stairs.

All through the building men at their desks, working by natural light, noticed the sudden darkness that fell as the winter wind blew the black smoke over the building. There were rapid steps, doors opening, and everywhere the news being passed from one to another. Each man raced to the heart of the building, the giant shell-shaped lecture hall in the center of the second floor, to see for himself. Just beneath the ceiling of the west wall, that which gave onto the picture gallery, the fire could be glimpsed gleaming through the ventilators. In the picture gallery itself a gaping hole in the ceiling where the plaster had fallen away showed the full extent of the blaze. The attic had been completely engulfed by roaring flames, and choking black smoke began to fill the tower offices.

Next page