I am deeply grateful to editor Rachel Kahan for first suggesting this story. My agent Deborah Clarke Grosvenor encouraged me to write it and, without her vision, the project would never have gotten off the ground. I have been very fortunate to have a fine editor in Claire Wachtel, whose enthusiasm has never flagged.

I would also like to thank Bill Cox at the Smithsonian Archives; Smithsonian paleontologist Ellis Yochelson for his ideas and materials; David Smith at the New York Public Library for always going beyond the call of duty; Rodolf De Salis for research help in London; Nausicaa Pouscoulous in Paris, Marc Rothenberg at the Smithsonian, Dr. Frank James at the Royal Institute, Neil Chambers at the Museum of Natural History in London; American historian Michael Conlin; Brian Dolan; Edwin Grosvenor; Pascale Heurteul at the Musee dHistoire Naturelle; Fabienne Queyroux at the Institut de France; Peter Schimkat; Jennifer Pooley at William Morrow; Allan Metcalf at MacMurray College for early support and Latin translation.

For lodging and laughs in Washington, D.C., thanks to DeeDee Slewka; for the same in New York, Ed Rollins.

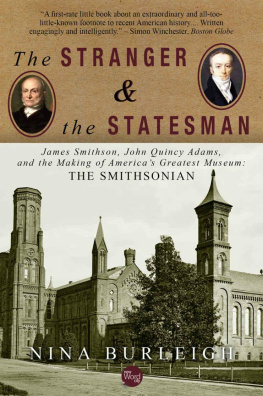

ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL did not spend the Christmas season of 1903 in the festive tradition. Instead the inventor of the telephone and his wife, Mabel , passed the holiday engaged in a ghoulish Italian adventure involving a graveyard, old bones, and the opening of a moldy casket. They had traveled by steamship from America at their own expense and made their way down to the Italian Mediterranean by train. The entire route was gloomy, as befit their mission. The feeble European winter sun dwindled at four oclock every afternoon and rain fell incessantly, but the Bells were undeterred. There was little time. They were in Europe to disinter the body of a minor English scientist who had died three-quarters of a century before and bring it back to America.

The couple arrived at Genoa a few days before Christmas and checked into the Eden Palace Hotel perched on the edge of the medieval port. The hotel was a pink, luxurious resort in summer, but in winter, drafty and exposed. The city itself spilled down the steep hillsides to the edge of the sea, a shadowy warren of fifteenth-century cathedrals and narrow, twisting alleys that had seen generations of plague, power, and intrigue. Once an international center of commerce and art, with palazzi and their fragrant gardens stretching to the waters edge, Genoa in winter at the turn of the twentieth century was a grim place with a harbor full of black, coal-heaped barges.

A steady rain had been falling on France and Italy for days, in Genoa whipped almost vertical by the tramontane, icy winds that blow down from the Alps into the Mediterranean in the winter. Mabel Bell had been hoping to alleviate the dolefulness of the duty by touring the city, but because of the weather she was unable to walk the alleys and visit the pre-Renaissance palazzi once inhabited by Genoas doges. She was forced to sit in the grand lobby of the Eden Palace Hotel, watching the palms beyond the rattling panes get thrashed in the wind, and wait as her husband sorted through the tangled bureaucracy involved in disinterring a body in Italy.

The Bells had come to Italy in haste because the remains of James Smithson - minor eighteenth-century mineralogist, bastard son of the first Duke of Northumberland, and mysterious benefactor of the Smithsonian Institution - were in peril. Seventy-seven years before, Smithson had, for unknown reasons, bequeathed his fortune - the equivalent of $50 million in current money - to the United States to fund at Washington, D.C., an institution, in his words, for the increase & diffusion of Knowledge among men. Now the bones of this strange and still little-understood man were about to be blasted into the oblivion of the Mediterranean Sea. Smithsonian officials had tried in early years to learn more about the obscure Englishman, but their attempts were largely fruitless and they abandoned the effort by 1903. To make matters worse, almost all of Smithsons personal effects and papers had been destroyed in a fire at the Smithsonian in 1865. To lose his bones to the sea would put an ignominious coda on the strangers murky life story.

The old British cemetery where he was buried occupied a picturesque plot of ground on a cliff overlooking the Mediterranean, but it was adjacent to a vast marble quarry. Blasting work to expand the port had been under way for years. The surface of the graveyard belonged to the British, but the hundreds of vertical feet of earth below extending to sea level belonged to the Italians. In 1900, the owners of the marble quarry had informed the British consulate that by the end of 1905, their blasting for marble would finally demolish the cemetery. When the Bells arrived, some coffins had already been dislodged from their graves, tipped over, and crashed into the gaping void below. The Italians were soon to evict all of the English dead in similar fashion.

By 1903, Alexander Graham Bell was fifty-six years old and one of Americas foremost scientists, a genuine celebrity whose name caused audiences to cheer and applaud. The telephone he had invented in his youth had changed the world radically in ways that he and his contemporaries understood and the American people appreciated. He had become a wealthy man because of the phone, but he never stopped inventing. He was responsible for a variety of firsts, including the first hydrofoil, the first respirator, the first practical phonograph, and the first metal detector (the last designed in frantic haste to locate the assassins bullet in President James Garfield), and he was involved with early experiments in flight. Bell was devoted to science as a kind of spiritual calling, and in his later years, his white beard and dignified bearing, coupled with his sonorous voice, gave him a Biblical air. When he realized his aerodrome, a watercraft on pontoons, was not airworthy, he wrote: There are no unsuccessful experiments. Every experiment contains a lesson. If we stop right here, it is the man that is unsuccessful, not the experiment.

Bells interest in the fate of Smithsons remains was purely altruistic. He was already wealthy and regarded as an American hero, and he had nothing to gain in terms of stature by making the journey himself. The old bones obviously held some scientific interest for him, but forensic anatomy was not one of his known interests. Rather, Bell, as a man of science, felt a certain spiritual kinship with the little-known scientist who had squirreled away a fortune to give to the United States. The idea of the benefactors bones being upended into the Mediterranean Sea had piqued him. He was the only member of the Smithsonian Board of Regents sufficiently moved to do anything about it.

Most of what we know about this trip comes from the journal kept by Mabel Bell, who had been deaf since childhood. Throughout their marriage, it had been her habit to record, in vivid detail, her and her husbands travels and adventures. Her journals and photographs offer a day-by-day account of the couples Christmas excursion to Genoa. Because of the weather, Mabel wasnt enjoying herself, but she was devoted to Alec, as she called her husband. On December 30, she sat in the entrance hall of the Eden Palace Hotel, with the cold wind blowing in through loosely hung glass doors and hugging the steam register for warmth. As the hotel staff moved about lighting lamps against the winter gloom, she pulled a great blue wool coat around her shoulders and wrote a letter to her daughter Daisy in Paris.