For A.P.; S.F.; and A.W.

wise friends

and L.M.B. with love

FAUST : The mob streams up to Satans throne;

Id learn things there Ive never known...

MEPHISTOPHELES : The whole mob streams and strives uphill:

One thinks ones pushing and ones pushed against ones will |

J. W. von Goethe, Faust |

Men never do evil so completely and cheerfully as when they do it from religious conviction |

Blaise Pascal, Penses |

However modern their terminology, however realistic their tactics, in their basic attitudes Communism and Nazism follow an ancient tradition and are baffling to the rest of us because of those very features that would have seemed so familiar to a chiliastic propheta of the Middle Ages. |

Norman Cohn, The Pursuit of the Millennium |

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Antony Harwood and Sally Riley of Gillon Aitken Associates have been the best literary agents one could hope for, as was David Godwin at an earlier stage in the proceedings.

Georgina Morley, Elisabeth Sifton and Walter H. Pehle brought a wealth of experience, insight and knowledge to a scrappy typescript, which Peter James then ironed out in detail with courtesy and patience. That we are all still talking is an unexpected bonus.

The archivists and librarians of the United States Holocaust Museum, Washington DC, the Zentrale Stelle des Landesjustizverwaltungen, Ludwigsburg, and the Wiener Library, London, facilitated the research for this book, although it is a work of interpretation rather than an archival monograph. I would especially like to thank Aaron Kornblum, Rosemarie Neif and, earlier, Christa Faqueur, ne Wichmann, for helping locate materials, a task which also befell my doughty research assistant, Joseph Whelan, one of several outstanding people it has been my good luck to teach, from whose insights I have benefited.

The time and space to embark on such a book was generously made available by Sir Brian Smith, the Vice-Chancellor of Cardiff University, while the British Academy and Wellcome Trust helped out with a small grant or two. A congenial intellectual environment to test out ideas was provided by Rutgers Universitys excellent Center for Historical Analysis. It is invidious to discriminate among my generous and sophisticated colleagues at Rutgers, but Omer Bartov and Matt Matsuda deserve my thanks for making such a refreshing year possible, while Jeremy, Frank, Max, Richard, Robert, Scott and Yosef kept me company on the doorstep. Agnes and Lynn provided exceptionally professional support services.

Those friends to whom I owe most of all come last. I would like to thank Amos, Desmond, Harvey, Jonathan, Adolf, John, Ian, Fritz, Niall, Steve and above all Richard (J. Overy) and Saul, for their constructive criticism of all or parts of the manuscript, or for supporting the author less directly, a debt which I would like to repay by dedicating the book to three of them. Thanking my wife seems superfluous, but she gets a separate dedication anyway.

Michael Burleigh

Lexington, Virginia

September 2000

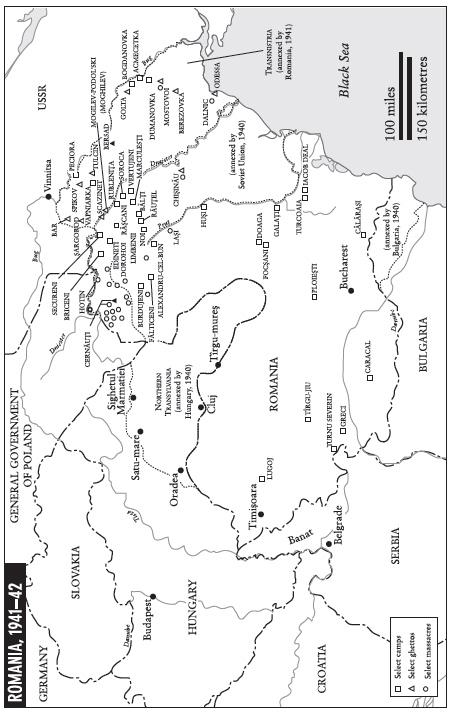

MAPS

INTRODUCTION AN EXTRAORDINARY RAPE OF THE SOUL: NATIONAL SOCIALISM, POLITICAL RELIGIONS AND TOTALITARIANISM

This book is about what happened when sections of the German elites and masses of ordinary people chose to abdicate their individual critical faculties in favour of a politics based on faith, hope, hatred and sentimental collective self-regard for their own race and

The book deals with the progressive, and almost total, moral collapse of an advanced industrial society at the heart of Europe, many of whose citizens abandoned the burden of thinking for themselves, in favour of what George Orwell described as the tom-tom beat of a latterday tribalism. They put their faith in evil men promising a great leap into a heroic future, with violent solutions to Germanys local, and modern societys general, problems. The consequences, for Germany, Europe and the wider world, were catastrophic, but no more so than for European Jews, who were subjected to a deliberate campaign to excise and expunge each and every one of them, which we rightly recognise as a uniquely terrible event in modern history.

In a local sense, Germany suffered its second massive and total defeat in the twentieth century. This was the price of mass stupidity and overweening ambition, paid with the lives of its citizens, whether directly compromised by dreadful crimes, or characterised by moral indifference or innocence. In a wider sense, other peoples were subjected to the compromises, indignities and terrors of this period should be exclusively fabricated in Germany, however much scholars there have contributed to knowledge and understanding of this dismal period of their contemporary history, which, in a profound sense, is not their own story.

Although this book has some thoughts about the ultimate horrors which Hitler and his subordinates were responsible for, it is not solely focused on

Rather, The Third Reich: A New History is an account of the longer-term, and more subtle, in general.

Although this book is subtitled A New History, its general approach has a lengthy intellectual pedigree, for this is emphatically not the first time that Nazism has been studied as a form either of political religion or of totalitarianism, though it is only since the early 1990s that these approaches have once again become fashionable. Its guiding ideas are more indebted to a number of philosophers, political scientists and historians of culture and ideas than to the general run of historians of this subject. In that sense, this book reasserts an important intellectual tradition, which sought to identify the essence of the Nazi phenomenon beneath the surface scratchings about whether Hitler slept with his niece, loved his dog or had plans for the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, relatively trivial matters which Heiden or Voegelin would have regarded with Olympian indifference. For, however unfashionable it may be, there are serious intellectual issues almost buried beneath the avalanche of morbid kitsch and populistic trivia which this subject generates, and from which no end or relief is in sight even sixty years later, a theme which in itself causes increasing unease among sophisticated contemporary observers. But lets turn now from these musings about our own time and culture to the ideas which have guided this books content, core concerns and structure.

Classical antiquity shaped most of our political vocabulary, leaving us such terms as democracy, despotism, dictatorship and tyranny. Occasionally, these words seemed insufficient to describe certain challenging developments, prompting commentators to seek new terms, sometimes in vain. Alexis de Tocqueville expressed this problem when he wrestled to describe North American democracy:

Next page