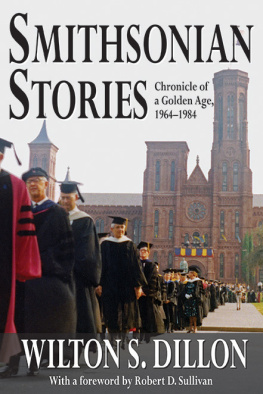

SMITHSONIAN

STORIES

SMITHSONIAN

STORIES

Chronicle of a Golden Age, 19641984

WILTON S. DILLON

With a foreword by Robert D. Sullivan

Transaction Publishers

New Brunswick (U.S.A.) and London (U.K.)

On the cover: Golden Age Pageantry: The pageantry of academic processions helped define the imagery of Smithsonian secretary S. Dillon Ripleys twenty-year reign, which was at its early stage when this photo was taken of scholars marching, with a mace, banners, and bagpipes, in September 1965 to commemorate the bicentennial of James Smithsons birth. The assembly set the stage for similar expressions of intellectual show business and showed the Institution as an enduring part of the world of higher learning. Photo: Smithsonian Institution Archives.

Copyright 2015 by Transaction Publishers, New Brunswick, New Jersey.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. All inquiries should be addressed to Transaction Publishers, 10 Corporate Place South, Piscataway, New Jersey 08854. www@transactionpub.com

This book is printed on acid-free paper that meets the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials.

Library of Congress Catalog Number: 2013044945

ISBN: 978-1-4128-5459-7

Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Dillon, Wilton S., 1923

Smithsonian stories : chronicle of a golden age, 19641984 : dedicated to S. Dillon Ripley (1913-2001) / by Wilton S. Dillon.

pages cm

Includes index.

ISBN 978-1-4128-5459-7 (cloth : alkaline paper)

1. Smithsonian Institution--History--20th century. 2. Dillon, Wilton S., 1923- 3. Ripley, S. Dillon (Sidney Dillon), 1913-2001. 4. Smithsonian Institution--Officials and employees--Biography. I. Title.

Q11.S8D55 2014

069.0975309045--dc23

2013044945

Dedication to

S. Dillon Ripley

Thanks for the Memory, the 1938 popular song identified with Bob Hope, comes to mind in my dedication of this book to Sidney Dillon Ripley (19132001), the eighth secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. The Smithsonian stories that follow serve as a testimony to the sources of my gratitude to him.

Ripley (no kin) gave me the opportunity to work and play at the Smithsonian for almost half of my ninety years on this small planet. I am privileged to return the favor by leaving this recordhowever uneven and incompleteof some little-documented aspects of his twenty-year reign, 19641984. In leaving these tracings, I pay homage also to The Education of Henry Adams and George Santayanas Persons and Places.

Sun King Ripley set into motion an institutional golden age that was inspired by his many gifts. Those influences are being felt today even by some ahistorical, now-oriented citizens who may not even have heard his namebelieve it or not. (The Smithsonian has joined other institutions in branding campaigns designed to appeal to youth perhaps more interested in quiz facts than intellectual ancestors.) Yet Ripley was a patrician-populist embracing all age grades and genders. He was also a believer in the potential power of scholars and other intellectuals to help fellow citizens understand the past, present, and future.

As I will tell, Ripley and I met first in Tokyo in 1946 when he was age thirty-two and I twenty-two. Encountering fellow Americans abroad can be a springboard to future associations back home. Though they never met, Ripley influenced another young man from the Americas. My fellow anthropologist Edgardo Carlos Krebs, an Oxford-trained Argentine, was inspired to serve the Smithsonian after reading, in Buenos Aires, a preface by Ripley in a book about the Smithsonians Museum of Natural History:

Ceremonial words are seldom memorable, but there was an lan vital in what Ripley wrote that matched my enthusiasm for that expensive, coveted book, full of illustrations of birds, mollusks, and other staples of cabinets of curiosity. Krebs found in Ripley resonance with naturalist-ornithologist William Henry Hudson (18411922). Hudson once collected bird skins for the Smithsonian and later wrote the 1904 novel Green Mansions.

Krebs continues, So I decided I liked Ripley not a politician, not a professional actor, not Hemingway, not a rock star, not a tycoon. He had much more in common with a French archetype, the serious cultural impresario, operating confidently over a wide public scenesomeone like Andr Malrauxthan anybody I could identify with in the U.S. When I finally made it to Washington, D.C., and saw the National Mall lined by museum buildings, several of them invented by Ripley, I realized the full scale of the lan vital I had noticed at play in the preface of that coveted book.

Despite contrasts between Ripley and Malraux, I applaud Krebss profile of a one-man UNESCO. Ripley set standards of leadership for generations to come.

Figure D.1. The Secretary and the Chancellor in Style

Chief Justice Warren Burger, chancellor of the Smithsonian, and Smithsonian Secretary S. Dillon Ripley at the opening ceremonies of 1876: A Centennial Exhibition, the US Bicentennial exhibition in the Arts and Industries Building, July 4, 1976. The image typifies the sense of style, history, and theater that marked the Ripley epoch.

Photo: Smithsonian Institution.

Joseph Henry and S. Dillon Ripley: Two Contrasting Visions for the Smithsonian Institution

Just what is the Smithsonian Institution? It most certainly is not a government agency, nor a component of the executive branch not a part of Congress or the Judiciary . Its administered independently by a Board of Regents like a private board of trustees a unique trust instrumentality created by act of Congress . If this all seems ambiguous, then I must say it is an ideal ambiguity. There are no limits to the research and artifact collections that the Smithsonian can pursue if it has the necessary funds.

William Whitesides Warner

In 1826, the last will and testament of British scientist James Smithson stipulated that if his nephew-heir were to die without children (which he did in 1835), then the estate was to be given to the United States to found at Washington, under the name of the Smithsonian Institution, an establishment for the increase and diffusion of knowledge among men.

The estate of one hundred thousand gold sovereigns was deposited in the Philadelphia mint in September of 1838. As old animosities die a lingering death, Congress and Andrew Jackson had the English coin re-minted into American gold currency with an endowment value of more than $500,000. After eight years of spirited debate (demonstrating that congressional intransigence is not a recent tradition), President James K. Polk established the Smithsonian Institution as a Federal Trust Entity on August 10, 1846, to be governed by the Board of Regents and the secretary of the Smithsonian. That original Board of Regents, composed of the chief justice of the United States, the vice president of the United States, the mayor of the City of Washington, three members of the US Senate, three members of the US House of set out to recruit the first Smithsonian secretary.

Science triumphs in you my dear friend & come you must. Redeem Washington. Save this great National Institution from the hands of charlatans . Come you

Next page