Acknowledgments

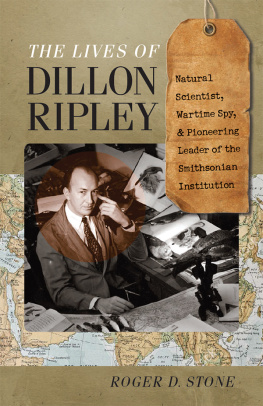

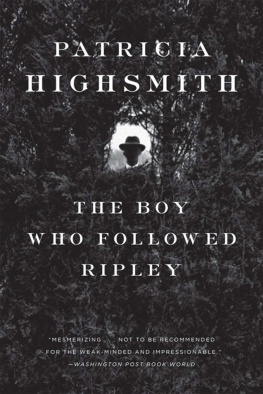

Its a crying need, said the Smithsonian veteran Marc Pachter when I told him I was working on a book about Dillon Ripley. He and others noted that, though the archives have an abundance of autobiographical material, third-party coverage of the full span of Ripleys life is in short supply. The New Yorker writer Geoffrey T. Hellman produced a fine profile in 1950. Various other mediathe Washington Post and the Washington Star, the Hartford Courantpublished profiles. Obituary pages gave Ripley ample space. But no one had yet gone through the archive box by box, folder by folder to assemble a more complete analysis of this mans remarkable record and how it evolved.

Starting out on my journey, I quickly found that most of those who had worked closely with Ripley were no longer with us, though there were a few exceptions. The foreign affairs practitioner Fisher Howe, who served under Ripley in the World War II Office of Strategic Services, was able to offer crisp memories a few days before his hundredth birthday. Ripleys events producer, Wilton Dillon (no relative), was just as articulate at age ninety-two. Paul Perrot had sharp and pleasant memories of his years as Ripleys principal museum professional. Tom Lovejoy, helpful as ever, offered sage advice across a broad spectrum, and warm memories, as well as this books much-appreciated foreword.

As for the rest, I had to rely in large measure on the rich trove of oral history materials that Ripley and others left behind. Especially useful was the set of forty audiotaped conversations with Ripley, most of them an hour or more in length. Almost all of them were transcribed, and those between 1977 and 1993 were compiled by Pamela M. Henson of the Smithsonian Institution Archives. My thanks to Ms. Henson for all she did to make these materials available to me and for commenting on portions of my manuscript. Ellen Alers of the same department was another valued member of the archival research team.

Elsewhere at the far-flung Smithsonian, there were many friendly faces. I especially appreciated the time spent with the ornithologist Bruce Beehler, who shares the enthusiasm Ripley had for the splendid birds of New Guinea and showed me the lab to which Ripley retreated when he could. Two other former Ripley assistants, Roger Pasquier and Warren King, offered warm thoughts. Amy Ballard and Rick Stamm supplied rich insight into the heart of the Smithsonian Castle. James Goode, George Watson, Carey Winfrey, Mary White, Phil Cook, Sally Maran, and Geoffrey La Riche all provided help. Dodge Thompson at the National Gallery of Art offered thoughts about the sometimes tense relationship between Ripley and the Gallery. Maygene Daniels, Anne Ritchie, and Jean Henry of the National Gallery Archive proffered backup materials. Cynthia Helms and Janet McClelland provided spirited thoughts about Washingtons Ripley-era cultural and social scene.

As for Yale, a former director of the Peabody Museum, Derek Briggs, took an interest in the project and gave me helpful entre to others, including the ornithologists Rick Prum and Kristof Zyskowski. The latter proudly presented Yales carefully maintained bird collection and carefully tagged examples of how Ripley fortified it. The staff of the Livingston Ripley Waterfowl Conservancy in Litchfield showed me and my family handsome ducks of many species. Charlie Roraback, a Yale classmate, drove me around and introduced me to Catherine Keene Fields, the cheerful director of the Litchfield Historical Society.

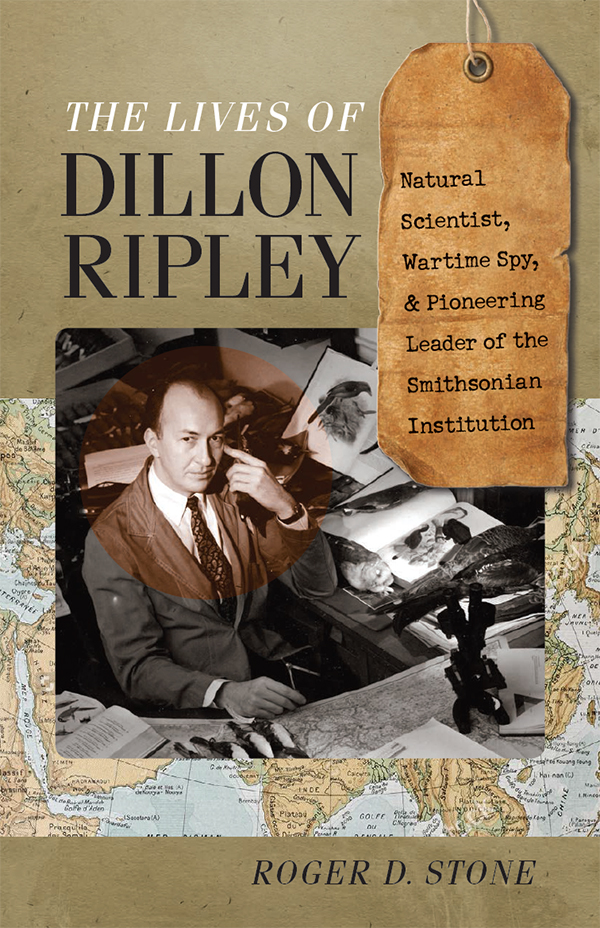

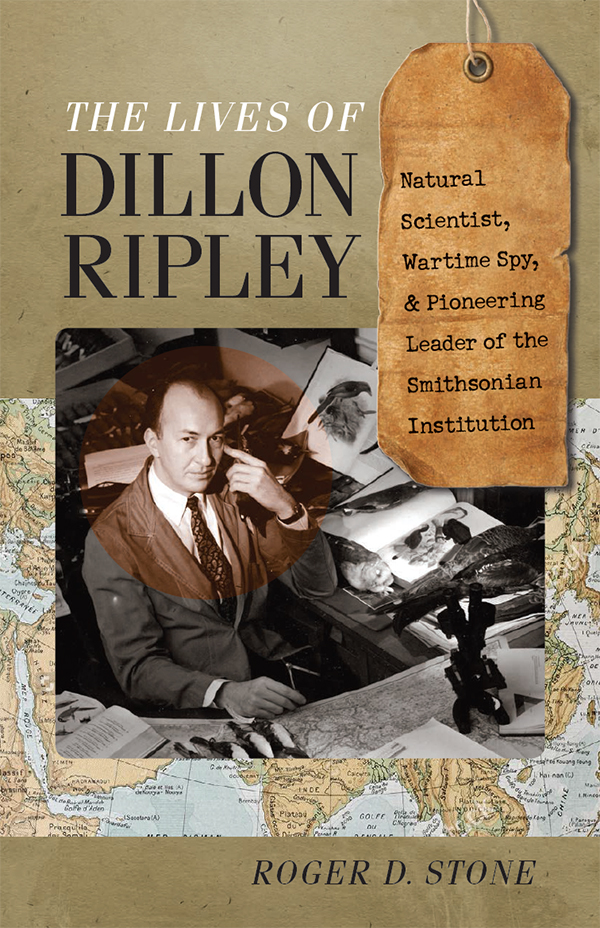

At my Washington office, the landlady, Grace Guggenheim, and her staff cheerfully provided invaluable extra services. So did my officemates down the hall, staff members of the Washington-based Bhutan Foundation: Bruce Bunting, Tshewang Wangchuk, Dawa Sherpa, and Tshering Yangzom, who, groaning, unfailingly responded to my plaintive queries about computer issues simple to them but beyond analog-minded me. Georgie Warner and Sylvia Ripley Addison combed the archives in search of the best among countless photographs to accompany the text.

Over the three-year life of the project, greatly needed financial support was received from numerous sources, including Christopher Addison, Douglas Banker, Wendy Benchley, William Bernhard and Catherine Cahill, Eleanor Briggs, Joan Challinor, William H. Draper III and Phyllis Draper, Alexander Farman-Farmaian, Elinor Farquhar, Hart Fessenden, Sally Fleming, Lee Folger and Juliet Folger, Aileen T. Geddes, Robert J. Geniesse, Nelse L. Greenway, Anita G. Herrick, David P. Hunt, Freeborn G. Jewett, Jr., Robert Leeson, Jr., John D. Macomber, Nicholas Millhouse, Gail Moloney, Gail Ostergaard, Rosemary Ripley, Sylvia Ripley, Hamilton Robinson, Jr., John Shober, Simon Sidamon-Eristoff, and Elsa Williams.

I owe great gratitude also to two gifted advisers who did much to improve the quality of this book: the editor and historical researcher Skip Moskey and the editorial consultant Colleen Daly; agent Carol Mann also helped a lot throughout the process. Doing the book with them was hard work; I cannot imagine doing it without their treasured assistance.

My wife, Flo, to whom this book is lovingly dedicated, helped in myriad ways. She, in the manner of Dillon Ripley, never gives up.

Roger D. Stone

Washington, DC

December 2015

Bibliography

Bartholomew-Feis, Dixee R. The OSS and Ho Chi Minh: Unexpected Allies in the War Against Japan. Lawrence: Kansas University Press, 2006.

Beehler, Bruce. A Naturalist in New Guinea. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1991.

Beehler, Bruce, Roger F. Pasquier, and Warren B. King. In Memoriam, S. Dillon Ripley. Auk 119, no. 4 (2002): 111013.

Bergin, Bob. OSS and Free Thai Operations in World War II. Studies in Intelligence 55, no. 4 (December 2011): 1122.

Burnham, Rika, and Elliott Kai-Kee. Teaching in the Art Museum: Interpretation as Experience. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2011.

Challinor, David. S. Dillon Ripley, 20 September 191312 March 2001. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 147, no. 3 (September 2003): 297302.

Conaway, James. The Smithsonian: 150 Years of Adventure, Discovery and Wonder. New York: Alfred E. Knopf, 1995.

Cruickshank, Charles. SOE in the Far East. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1983.

Dillon, Wilton. Smithsonian Stories: Chronicle of a Golden Age, 196484. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Press, 2015.

Ewing, Heather. The Lost World of James Smithson. London: Bloomsbury, 2007.

Ewing, Heather, and Amy Ballard. A Guide to Smithsonian Architecture. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Books, 2009.

Graham, Katharine, ed. Katharine Grahams Washington. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2002.

Harris, Neil. Capital Culture. Chicago: Chicago University Press, 2013.

Hellman, Geoffrey T. Curator for Getting Around. New Yorker, August 26, 1950, 3149.

. The Smithsonian: Octopus on the Mall. New York: Lippincott, 1966.

Henson, Pamela M. Oral History Interviews of S. Dillon Ripley (19971993). Smithsonian Institution Archives, Record Unit 009591.

Henwood, Doug. Spooks in Blue. Grand Street (Spring 1988).

Hurrell, Andrew, and Benedict Kingsbury. The International Politics of the Environment: Actors, Interests, and Institutions. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992.

Lardner, James. S. Dillon Ripley, Keeper of the Castle. Washington Post, November 7, 1982.

Lewis, Michael L. Inventing Global Ecology: Tracking the Biodiversity Ideal in India, 19471997. Athens: Ohio University Press, 2004.

Next page