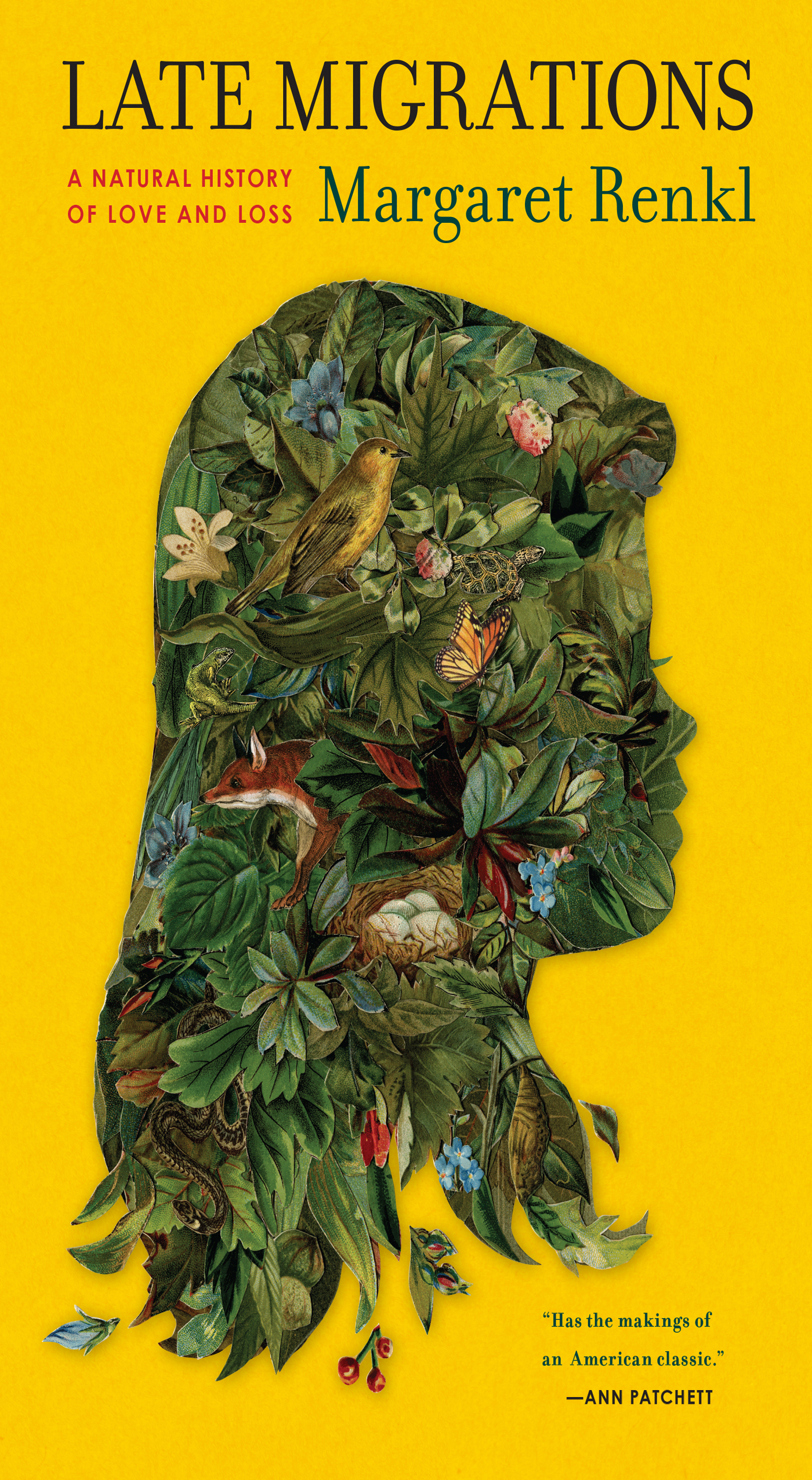

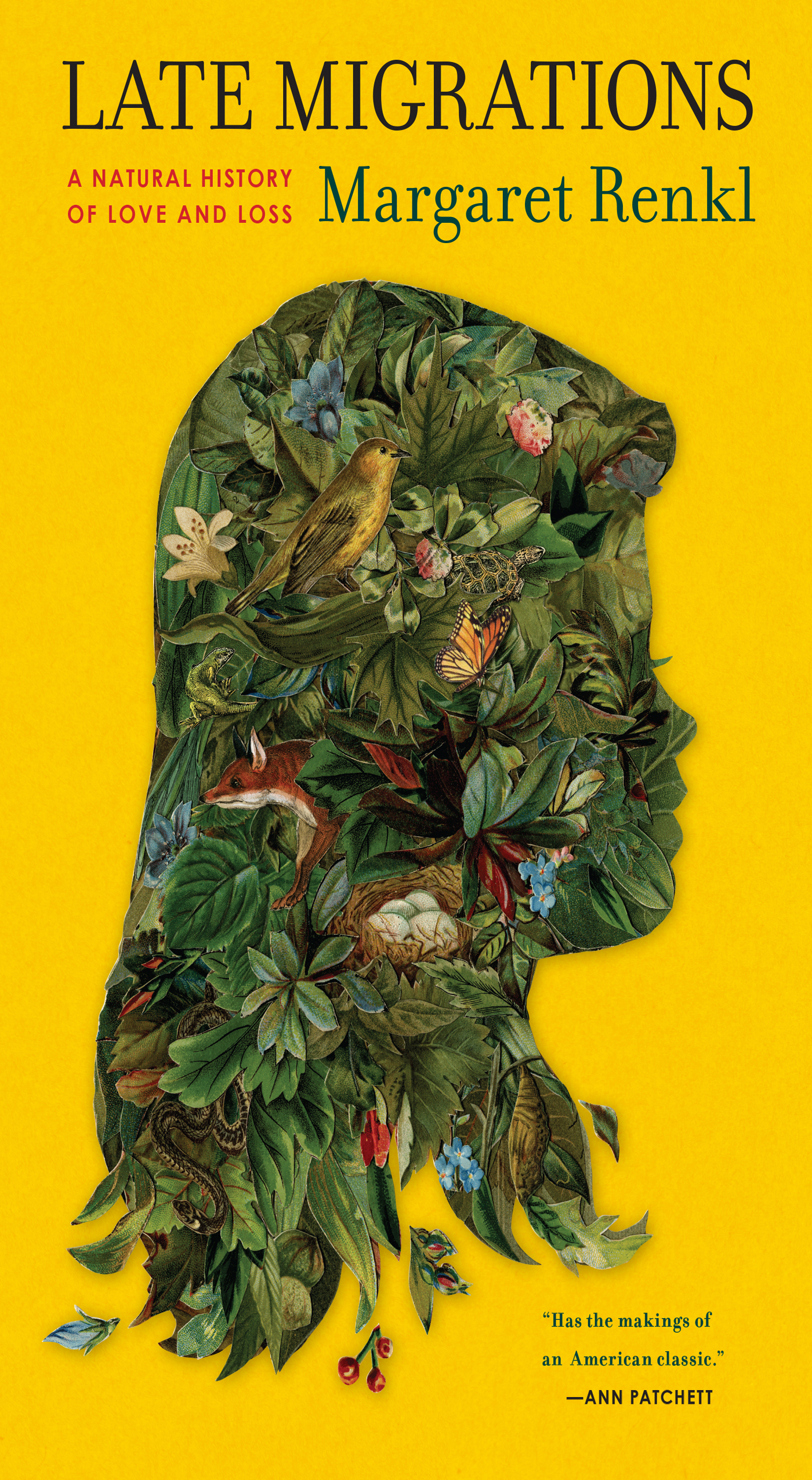

LATE MIGRATIONS

LATE MIGRATIONS

A Natural History of Love and Loss

Margaret Renkl

With art by

Billy Renkl

MILKWEED EDITIONS

2019, Text by Margaret Renkl

2019, Art by Billy Renkl

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in critical articles or reviews, no part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without prior written permission from the publisher: Milkweed Editions, 1011 Washington Avenue South, Suite 300, Minneapolis, Minnesota 55415.

(800) 520-6455

milkweed.org

Published 2019 by Milkweed Editions

Printed in Canada

Cover design by Mary Austin Speaker

Cover art by Billy Renkl

19 20 21 22 23 5 4 3 2 1

First Edition

Milkweed Editions, an independent nonprofit publisher, gratefully acknowledges sustaining support from the Ballard Spahr Foundation; the Jerome Foundation; the McKnight Foundation; the National Endowment for the Arts; the Target Foundation; and other generous contributions from foundations, corporations, and individuals. Also, this activity is made possible by the voters of Minnesota through a Minnesota State Arts Board Operating Support grant, thanks to a legislative appropriation from the arts and cultural heritage fund. For a full listing of Milkweed Editions supporters, please visit milkweed.org.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Renkl, Margaret, author. | Renkl, Billy, illustrator.

Title: Late migrations : a natural history of love and loss / Margaret Renkl ; with art by Billy Renkl.

Description: First edition. | Minneapolis : Milkweed Editions, 2019.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018044003 (print) | LCCN 2018057281 (ebook) | ISBN 9781571319876 (ebook) | ISBN 9781571313782 (hardcover : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Renkl, Margaret. | Renkl, MargaretFamily. | JournalistsUnited StatesBiography. | Adult children of aging parentsUnited StatesBiography.

Classification: LCC PN4874.R425 (ebook) | LCC PN4874.R425 A3 2019 (print) | DDC 818/.603 [B]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018044003

Milkweed Editions is committed to ecological stewardship. We strive to align our book production practices with this principle, and to reduce the impact of our operations in the environment. We are a member of the Green Press Initiative, a nonprofit coalition of publishers, manufacturers, and authors working to protect the worlds endangered forests and conserve natural resources. Late Migrations was printed on acid-free 100% postconsumer-waste paper by Friesens Corporation.

For my family

Contents

Well, dear, life is a casting off. Its always that way.

ARTHUR MILLER, DEATH OF A SALESMAN

Therefore all poems are elegies.

GEORGE BARKER

LATE MIGRATIONS

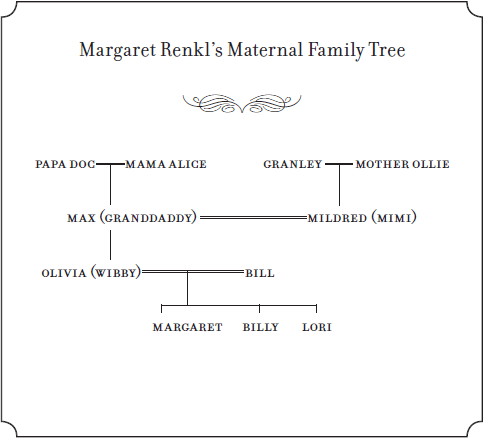

In Which My Grandmother Tells the Story of My Mothers Birth

LOWER ALABAMA, 1931

W e didnt expect her quite as early as she came. We were at Mothers peeling peaches to can. Daddy had several peach trees, and they had already canned some, and so we were canning for me and Max. And all along as I would peel I was eating, so that night around twelve oclock I woke up and said, Max, my stomach is hurting so much I just cant stand it hardly. I must have eaten too many of those peaches.

And so once in a while, you see, it would just get worse; then it would get better.

We didnt wake Mother, but as soon as Max heard her up, he went in to tell her. And she said, Oh, Max, go get your daddy right now! Maxs daddy was the doctor for all the folks around here.

While he was gone she fixed the bed for me, put on clean sheets and fixed it for me. Mama Alice came back with him tooMama Alice and Papa Doc. So they were both with me, my mother on one side and Maxs on the other, and they were holding my hands. And Olivia was born around twelve oclock that day. I dont know the time exactly.

Max was in and out, but they said Daddy was walking around the house, around and around the house. Hed stop every now and then and find out what was going on. And when she was born, it was real quick. Papa Doc jerked up, and he said, Its a girl, and Max said, Olivia.

Red in Beak and Claw

T he first year, a day before the baby bluebirds were due to hatch, I checked the nest box just outside my office window and found a pinprick in one of the eggs. Believing it must be the pip that signals the beginnings of a hatch, I quietly closed the box and resolved not to check again right away, though the itch to peek was nearly unbearable: Id been waiting years for a family of bluebirds to take up residence in that box, and finally an egg was about to shudder and pop open. Two days later, I realized I hadnt seen either parent in some time, so I checked again and found all five eggs missing. The nest was undisturbed.

The cycle of life might as well be called the cycle of death: everything that lives will die, and everything that dies will be eaten. Bluebirds eat insects; snakes eat bluebirds; hawks eat snakes; owls eat hawks. Thats how wildness works, and I know it. I was heartbroken anyway.

I called the North American Bluebird Society for advice, just in case the pair returned for a second try. The guy who answered the help line thought perhaps my bluebirdsnot mine, of course, but the bluebirds I lovedhad been attacked by both a house wren and a snake. House wrens are furiously territorial and will attempt to disrupt the nesting of any birds nearby. They fill unused nest holes with sticks to prevent competitors from settling there; they destroy unprotected nests and pierce all the eggs; they have been known to kill nestlings and even brooding females. Snakes simply swallow the eggs whole, slowly and gently, leaving behind an intact nest.

The bluebird expert recommended that I install a wider snake baffle on the mounting pole and clear out some brush that might be harboring wrens. If the bluebirds returned, he said, I should install a wren guard over the hole as soon as the first egg appeared: the parents werent likely to abandon an egg, and disguising the nest hole with a cover might keep wrens from noticing it. I bought a new baffle, but the bluebirds never came back.

The next year another pair took up residence. After the first egg appeared, I went to the local bird supply store and asked for help choosing a wren guard, but the store didnt stock them; house wrens dont nest in Middle Tennessee, the owner said. I know they arent supposed to nest here, I said, but listen to what happened last year. He scoffed: possibly a migrating wren had noticed the nest and made a desultory effort to destroy it, but there are no house wrens nesting in Middle Tennessee. All four bluebird eggs hatched that year, and all four bluebird babies safely fledged, so I figured he must know this region better than the people at the bluebird society, and I gave no more thought to wren guards.

Next page