NEW AMERICAN LIBRARY

Published by Berkley

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014

Copyright 2016 by Elizabeth Rynecki

Penguin Random House supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for every reader.

New American Library and the NAL colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Text photos courtesy of the Rynecki family except as follows: p. 95 courtesy of Mitchell Schwarzbach; pp. 226228, 23738, and 267 courtesy of the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto; p. 247 courtesy of Elizabeth Rynecki Fisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Rynecki, Elizabeth, author.

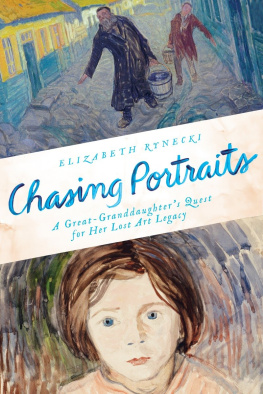

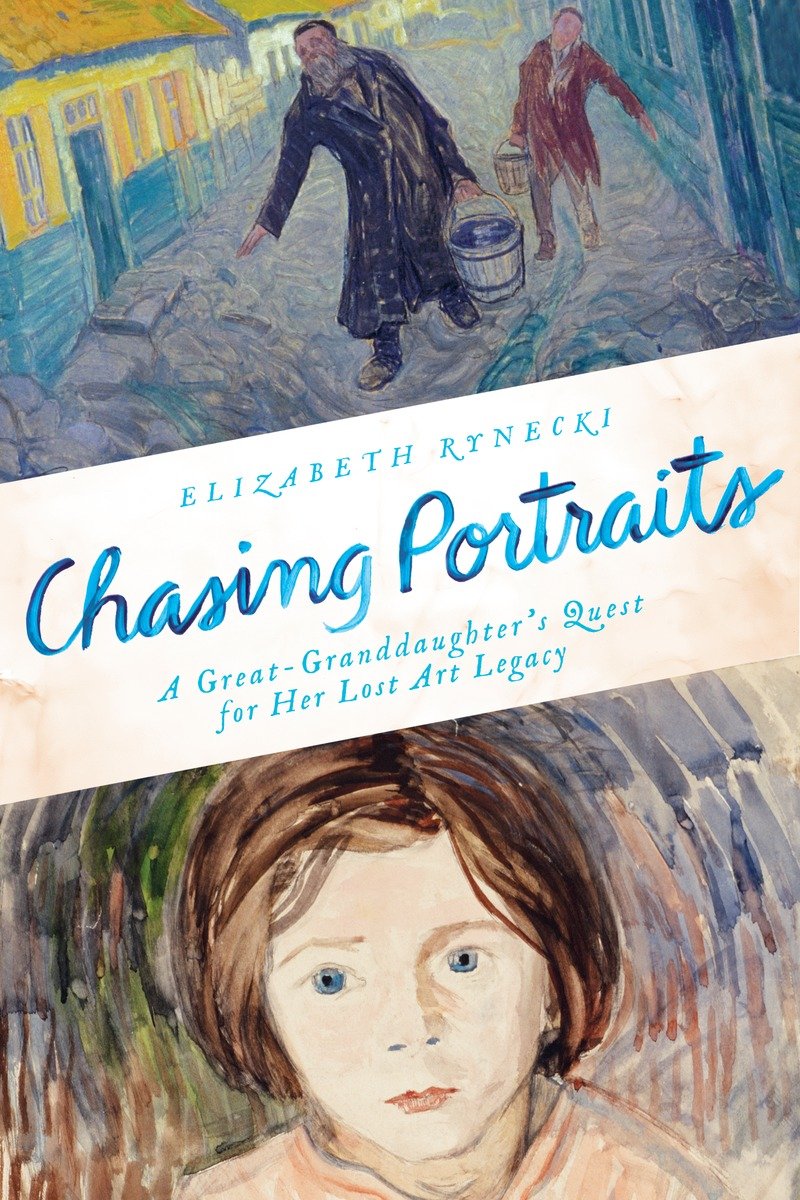

Title: Chasing portraits: a great-granddaughters quest for her lost art legacy/Elizabeth Rynecki.

Description: First edition. | New York: NAL, New American Library, [2016] | 2016

Identifiers: LCCN 2016012588 (print) | LCCN 2016013257 (ebook) | ISBN

9781101987667 (hardback) | ISBN 9781101987681 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Rynecki, Moshe, 18811943. | Rynecki, Moshe,

18811943Appreciation. | Jewish artistsPolandBiography. | Art,

Polish20th century. | Jews in art. | BISAC: BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY/

Personal Memoirs. | HISTORY/Jewish. | HISTORY/Holocaust.

Classification: LCC N7255.P63 R9637 2016 (print) | LCC N7255.P63 (ebook) |

DDC 700.92dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2016012588

First Edition: September 2016

Jacket artwork by Moshe Rynecki; courtesy of the author

Jacket design by Emily Osborne

Title page art Valentin Agapov/Shutterstock Images

While the author has made every effort to provide accurate telephone numbers and Internet addresses at the time of publication, neither the publisher nor the author assumes any responsibility for errors, or for changes that occur after publication. Further, publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Version_1

For my great-grandfather

who persisted in his passion for painting.

Culture belongs to all of us.

CONTENTS

PREFACE

I was born in San Francisco on a summer day in 1969, just over twenty-five years after my great-grandfather perished in the Holocaust. My life began in a modern hospital with the prospect of a war-free childhood. Until I was forty-five I had never visited Poland. I tell you this to emphasize the fact that I am not a Holocaust survivor; I cannot bear witness to a past I did not personally experience and which seemed distant and tangential to me. I am, however, distinctly connected to the history of the Holocaust through the legacy of my great-grandfathers art.

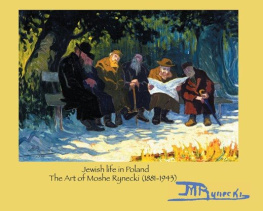

I grew up with many of my great-grandfathers paintings on the walls of my childhood home. Moshe Rynecki (18811943) painted scenes detailing the everyday lives of Polish Jews in the 1920s and 1930s. His depictions of woodworkers, water carriers, women sewing, men studying the Talmud, even street performers, were the background of my childhood.

Moshe was a prolific artist whose work was exhibited in Warsaw and featured in a number of newspapers (both Polish and Yiddish) in his lifetime. Although he was known in Warsaw before the Second World War, he was not particularly famous.

Moshe was never supposed to be an artist. He had been born into a religious Jewish family in Poland, and painting was not on the short list of acceptable career options. My great-grandfather didnt care. He loved to draw and paint, even if it got him in trouble, which it sometimes did.

Moshe eventually grew up and left home. He lived in Warsaw, in a non-Jewish part of town, and led a surprisingly assimilated life. He and his wife, Perla Rynecki (ne Mittelsbach), ran an art supply store. To be fair, Perla managed the store and family life, while Moshe went out into the world to paint. He painted constantly. By the time the Nazis invaded Poland on the first of September in 1939, he had painted more than eight hundred artworks and sculpted a number of pieces as well.

Moshe continued to paint after the Nazi invasion, but as conditions for Jews worsened, he became worried about protecting his body of work. At that point my great-grandfather made the fateful decision to divide his paintings and sculptures into bundles and to ask friends and acquaintances to hide them. To those who agreed, he promised he would return after the war ended (whenever that might happen) to retrieve the bundles. Soon after, Moshe willingly went to live in the Warsaw Ghetto. His son, my Grandpa George, who lived with false papers in a Polish neighborhood in Warsaw, begged his father not to go. And when conditions in the ghetto worsened, George offered to find a way to get Moshe out. But Moshe didnt want to leavehe wanted to be with his peopleand whatever happened to them would happen to him. If its death, so be it, he said the last time he ever spoke with his son.

Though Moshe was ultimately deported and murdered by the Nazis, his wife, Perla, managed to survive the Holocaust. After the war she did her best amid the near total devastation in and around Warsaw to recover her husbands art. Ultimately, she found only 120 paintings, stashed in a cellar in the Praga district of the city. Grandpa George wrote in his reminiscences of the war years that his mother finding them was a miracle. For more than fifty years, my family assumed all that remained of my great-grandfathers collection was the work Perla had recovered.

In 1999 I built a website dedicated to sharing my great-grandfathers art. At first not much happened, but over time, with the help of information I found posted on the Internet, friendships I made on social media, and the kindness of strangers, I began to find clues that more of my great-grandfathers paintings had survived the Second World War. Sometimes I discovered accession numbers of works held by museums, but no other information; other times I found photos of the works but no clues as to the location or holders of the originals; and sometimes I lucked out and private collectors with my great-grandfathers paintings contacted me. Of course, not everyone who had my great-grandfathers artwork wanted to speak to me. Some were afraid of the great-granddaughter asking for pictures and information about how the paintings were obtained. Others were more generous, sending photographs of Rynecki paintings in their possession and even allowing me into their homes to see the works and interview them. As my project gained momentum, and I spoke to more people about my search, I heard from others what Id always felt personally: not only was the story amazing, but the art was beautiful.

There would be no story to tell if the Holocaust had not happened, but this story is less about the Shoah and more about my great-grandfathers art and what happened to his body of work in the aftermath of the Second World War. If the paintings could speak, it would be their story to tell. But they cannot, and so I wrote this book to share my story of discovery.