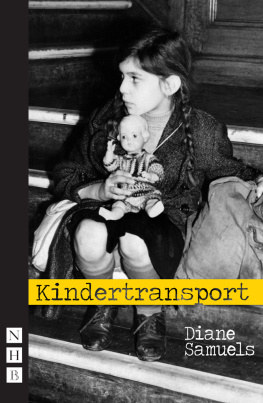

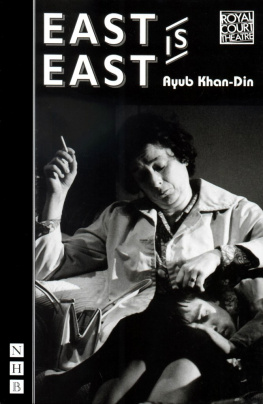

Diane Samuels KINDERTRANSPORT  NICK HERN BOOKS London www.nickhernbooks.co.uk

NICK HERN BOOKS London www.nickhernbooks.co.uk

Introduction

Three incidents led me to write

Kindertransport. The first was a discussion with a close friend, in her late twenties and born into a comfortable, secure home, who described her struggle to deal with the guilt of survival. Her father had been on the Kindertransport and I was struck by how her parents feelings had been passed down to her. The second was the experience of another friend who, at his fathers funeral, overheard his mother recalling her time at Auschwitz. Until that moment he had had no idea that his mother had been in a concentration camp. The third was the ashamed admission by a fifty-five-year-old woman on a television documentary about the Kindertransport, that the feeling she felt most strongly towards her dead parents was rage at their abandonment of her, even though that abandonment had saved her life.

In 1989, I was a young mother with a one-year-old son and pregnant with my second child when I saw this TV documentary. I was struck at once by the ways in which parents and children struggled to deal with this desperate parting. I never intended to write Kindertransport as a modern history play. I wanted to explore the universal human experience of separation of child from parent, of refugee from the source of their culture or motherland. I let this theme mull, up to my ears in nappies and baby milk, for a while longer. In 1991, I wrote a scene between two German Jews.

A mother hovers over her nine-year-old daughter and hands a new coat to the child. It is too big because it must last for next winter too. She gives the girl a button and some thread and then coolly instructs her how to sew the one onto the other. By this time, my young sons were not yet one and not quite three. Artists are often drawn to the extremes of human experience in order to reflect also upon what is ordinary. Kinder, now in their seventies and eighties, have, on seeing the play, asked me, How can you possibly understand my experience so deeply? I reply that as a young mother myself I couldnt help but be touched by what had happened to them.

I was compelled to get to the heart of the dilemma. Ask a child if they would prefer to be sent away to safety if their family is in mortal danger, and he or she will, in most cases, say that theyd rather stay and die with their parents. Ask a parent what they would do in the same situation and most would say that theyd send away their child to be safe. To be a parent is to live with this hidden contradiction. I wanted to try to face it. In 2007, when the play was revived for a national tour of the UK, my eldest son was eighteen and left home to go to university.

How Life reflects Art. I found myself watching actresses in auditions read the scene in which English Evelyn loads her daughter Faith with crockery for her student flat. Then I went home and hours later loaded my boy with mugs for his student flat. I wonder at how I could understand Evelyns suppressed heartache at Faiths departure when my children were still so young and at home with me. But many parents, from the second their child is born, know too well that here begins the road to seeing their offspring on their way. The bittersweet task is to prepare their child to manage entirely without them.

Past and present are wound around each other throughout the play. They are not distinct but inextricably connected. The re-running of what happened many years ago is not there to explain how things are now, but is a part of the inner life of the present. I interviewed a number of the Kinder as part of my research. They were all very open about their lives and feelings. Many of their actual experiences are woven into the fabric of the play.

Although Eva/Evelyn and her life are fictional, most of what happens to her did happen to someone somewhere. I used to dedicate this play to those Kinder and the rest of the 10,000 who left Europe over seventy years ago. Now I see that, by entering the exceptional experience of those children who caught the trains to safety when many of them, like Eva, were too young to bear it, a crucial connection can be made with the clinging child inside us all that never wants to let go, no matter what. So, now I dedicate the play also to those fortunate children who have the opportunity to leave their parents when they are ready. And to the parents who raise their children to take that leave. No child, as Evelyn must struggle so painfully to accept, can be my little girl, or boy, forever, if they are to thrive.

DIANE SAMUELS London, 2008

Thanks

Many thanks to Libby Mason; Mark Ravenhill; Jack Bradley; Abigail Morris; Soho Theatre Company; Rena Gamsa; Dawn Waterman; Naomi Fulop; Erica Burman; and particularly to Ben and Jake. Special thanks to the Kinder who were interviewed as part of research for the play: Walter Fulop; Bertha Leverton; Paula Hill; Vera Gissing and Lisa who talked at length about their journeys and their lives.

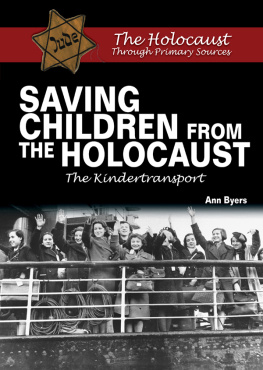

Background to the Kindertransport

The Nazi gaining of power in the 1930s signalled a huge escalation in anti-semitic activity. The first organised attack on the Jews was in April 1933 a boycott of Jewish businesses was instigated and triggered much violence. A series of laws ensued, increasingly excluding Jews from public life. The most notorious of these were the Nuremberg Laws the Reich Citizenship Act, depriving Jews of their citizenship, and the Act for the Protection of German Blood and German Honour.

This latter law prohibited marriage or extramarital relations between Jews and nationals of German or allied blood in order to ensure the survival of the German race. Later measures required that all Jewish passports were marked with the letter J in addition Jews were banned from places of public entertainment and cultural institutions, had their driving licences revoked, their property confiscated and were often forced to live together in communal Jewish houses. The killing of a German diplomat by a young Jew in Paris in November 1938 gave the Nazis the opportunity to engineer a huge increase in momentum. Thousands of Jewish businesses and institutions were destroyed and Jews were assaulted, killed and 30,000 herded into concentration camps. It was in response to this pogrom, known as Kristallnacht, that the Movement for the Care of Children from Germany was formed, rescuing almost 10,000 unaccompanied children, before the outbreak of war just nine months later.

Personal Accounts of the Kindertransport

I took a bus to Dovercourt where I was told help was needed at a refugee camp.

This was in 1938 when the Committee for the Care of Children from Germany took over a holiday camp to act as a reception centre for Jewish refugee children. Through this camp came children from Germany, Austria and even a few stray Sudetenlanders. At one time when I first was there nearly seven hundred children arrived every week, their passports altered so that all the boys were Jacob and the girls Sarah, carrying pathetic paper bags containing a few spare clothes and little else. The Germans had stripped them of everything that was worth a pfennig. The children had a big J marked on their passports so that everyone would know they were of the despised race. Their ages were at the youngest four and the oldest I remember was sixteen.

The camp was full. As many as came in had to be found places so as to allow room for the next batch. Some children went to relatives in America, many were taken in by families in Britain. Some were even sent to a settlement in Paraguay. Did they, I now wonder, ever come into contact with the Nazis who escaped from Germany and found haven there? An impressive elderly lady, Anna Essinger who had a school in Kent was in charge of the camp and managed, somehow, to shape the ad hoc collection of volunteers into something of an effective organisation. It cannot have been easy: excitable young Viennese, less mercurial German ones, volunteers like myself who arrived by accident and a sprinkling of young Etonians and undergraduates meant there was plenty of energy all needing firm but diplomatic direction.

Next page

NICK HERN BOOKS London www.nickhernbooks.co.uk

NICK HERN BOOKS London www.nickhernbooks.co.uk