One

PRIOR TO 1900 RAVINES, RAILROADS, AND BIG TREES

Before settlers came, the principal feature of Ravenna was the creek that drained Green Lake and emptied into Union Bay. Glacial melt-off formed the wooded ravine, and Native Americans lived in a village on the shore of Union Bay. In 1852, David Doc Maynard arrived in the area. Reportedly he named Seattle after his friend Chief Sealth, leader of the Duwamish and Suquamish tribes. Henry Yesler opened his sawmill in 1853, and in 1861, Washington Territorial University was established. By 1870, Seattles population was 1,107.

The Ravenna area would have several owners before increasing in value in the mid-1880s when the Seattle, Lake Shore, and Eastern Railroad extended up the shore of Lake Washington from Seattle. By this time, Seattles population had grown to 3,533. In 1887, George and Oltilde Dorffel were the owners. The area still possessed its old-growth timber, and they designated the ravine as a park, likely because the steep topography would make building problematic. Ravenna became a stop on the new railroad.

In 1888, Rev. William W. Beck and his wife, Louise, purchased 400 acres on Union Bay. They developed the property around Ravenna station and set aside 10 acres for the Seattle Female College. Beck also opened the Ravenna Flouring Company. The Becks fenced the ravine and opened Ravenna Park. They imported exotic plants and built paths, picnic shelters, and fountains. Admission was 25.

Washington Territory became Washington state in 1889, the same year as the Great Seattle Fire and the dedication of Calvary Cemetery. By 1890, Seattles population had grown to 43,487, an increase of approximately 40,000 people in 10 years. The population of Ravenna in 1892 was 50. By this time, Ravenna also had a grocery store, general store, and post office. On July 17, 1897, the steamer Portland arrived in Seattle with a ton of gold, a phrase coined by Erastus Brainerd, press agent for the Seattle Chamber of Commerce, and Beriah Brown Jr. at the Seattle Post-Intelligencer . Seattles population and economy grew rapidly after this, as Seattle became the port that would supply the gold fields of Alaska and the Yukon.

Reverend Beck was a real estate developer who marketed Ravenna as Seattles most desirable suburb in the 1890s. He purchased 400 acres on Union Bay and developed the property around the Ravenna station of the Seattle, Lake Shore, and Eastern Railroad into town lots. This photograph shows the area around what is now NE Sixty-fifth Street and Ravenna Avenue NE with a sign offering half-acre home tracts. (Courtesy Jay Milton.)

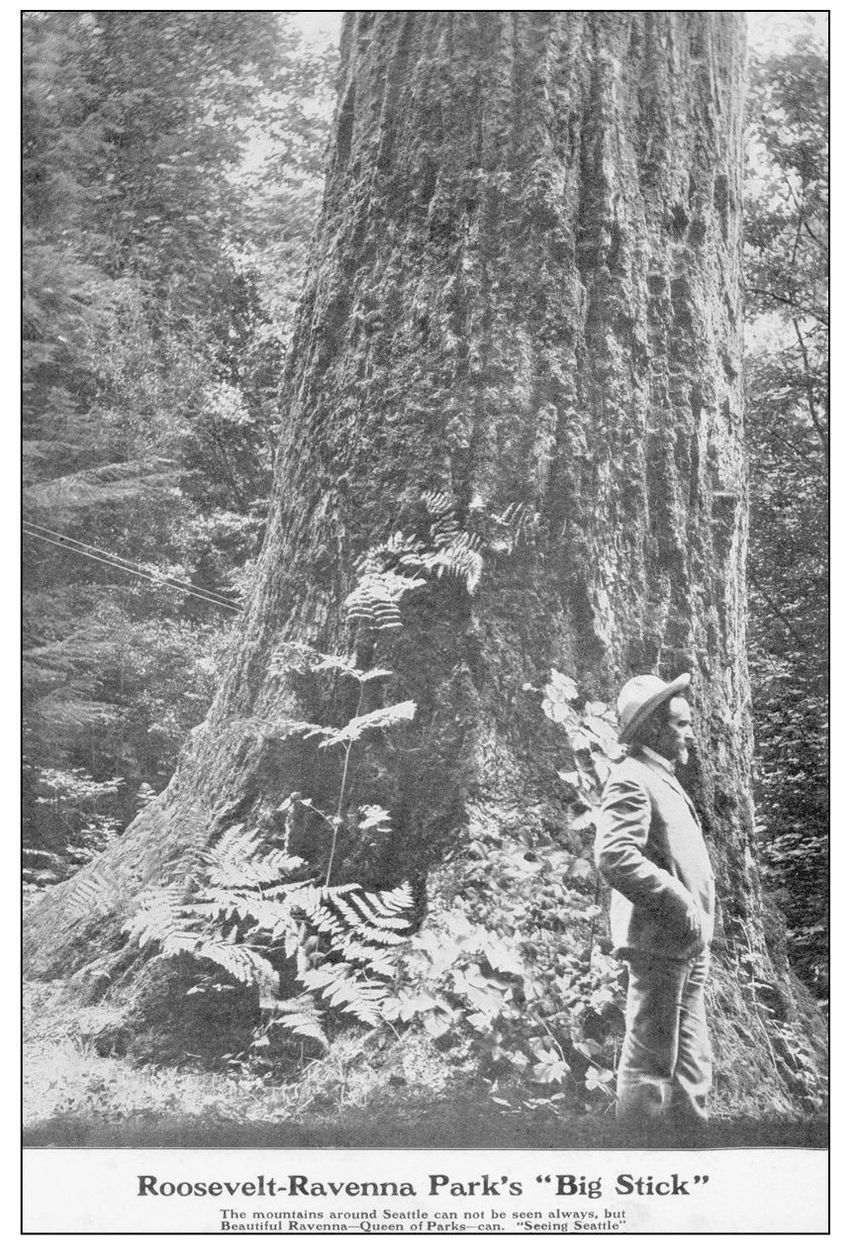

This poster of Beck shows him standing by Roosevelt-Ravenna Parks Big Stick. The front states, The mountains around Seattle can not be seen always, but Beautiful RavennaQueen of Parkscan. The back has a notation that says, Uncle Wirt standing beside the Big Tree. In 1890, there was a sign on this tree that read, measures 44 ft around, 18 in above the ground. (Courtesy Peter Blecha.)

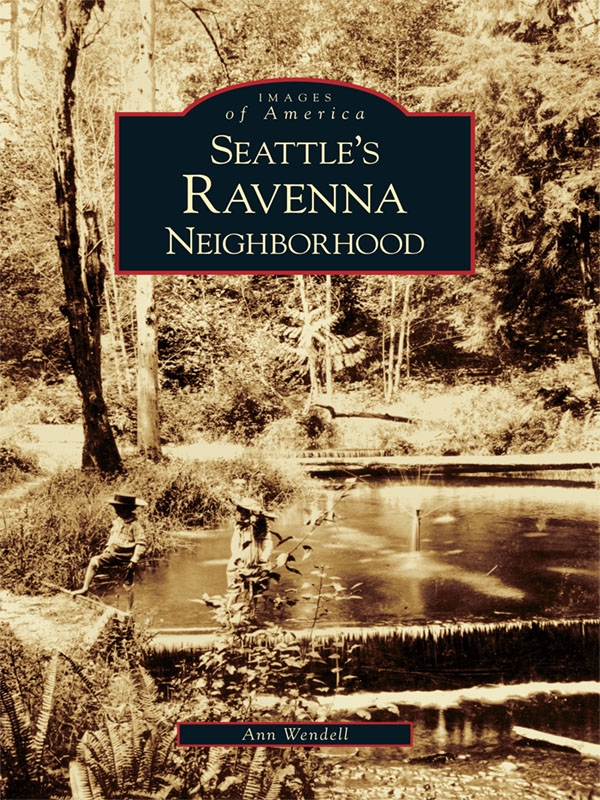

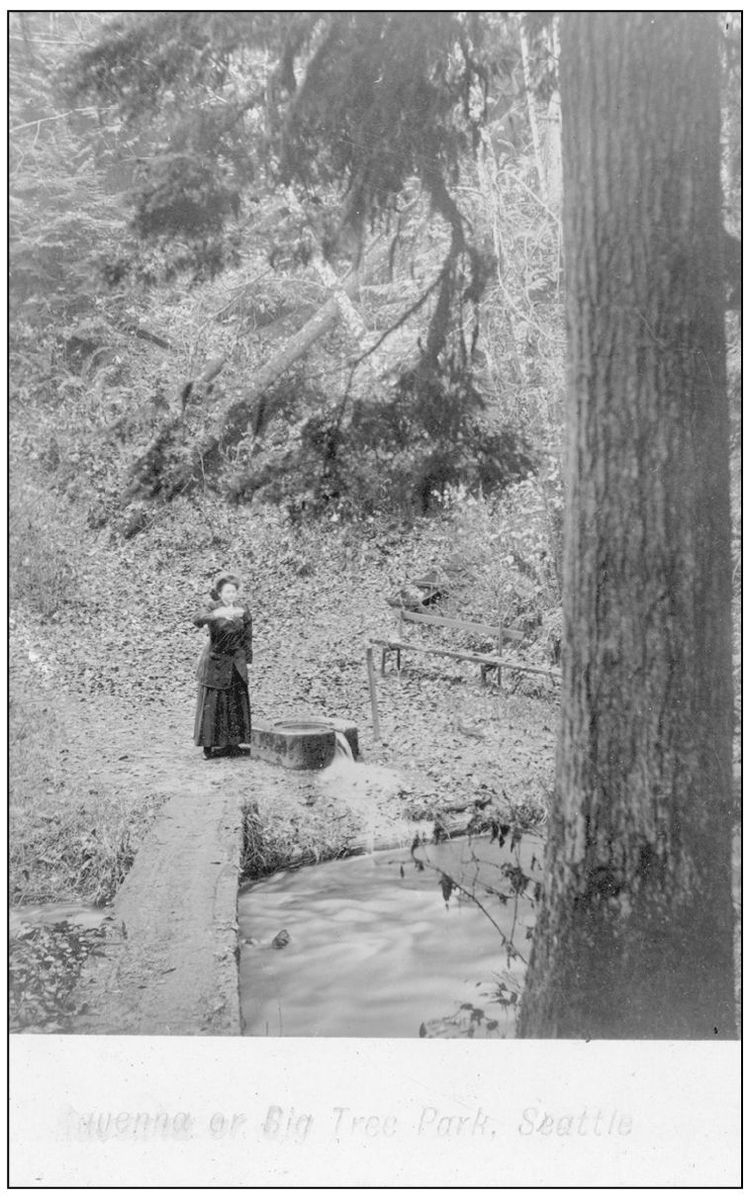

A woman stands beside and appears to be partaking of Ravenna Parks mineral springs. At the time, there were over 40 springs in the park, including Mineral Spring, already well known to visitors; the Lemonade Spring near the big trees; Petroleum Springs in the center of the park; and a larger Mineral Spring in the upper creek bed. (Courtesy Peter Blecha.)

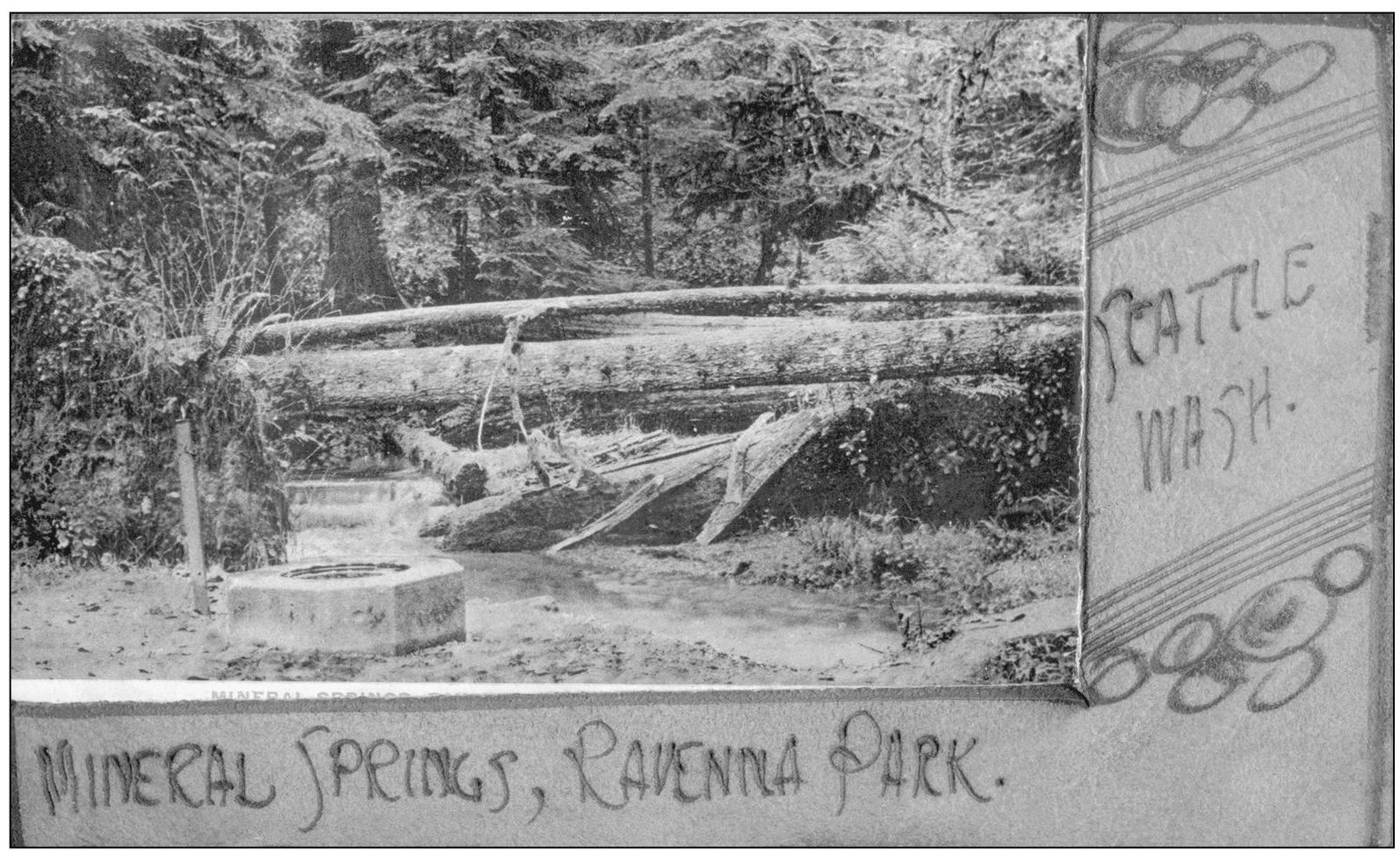

This glimpse of Mineral Spring was made into a postcard. The surround is made of leather with the words Mineral Springs, Ravenna Park. Seattle, Wash. burned into it. The 1903 Ravenna Park Im Walde said, Ravenna Park will ... be the Kohinoor of parks to him who takes time to breathe its air, drink its waters, rest his eyes on its vegetation, and listen to the songs in trees and canyons. (Courtesy Peter Blecha.)

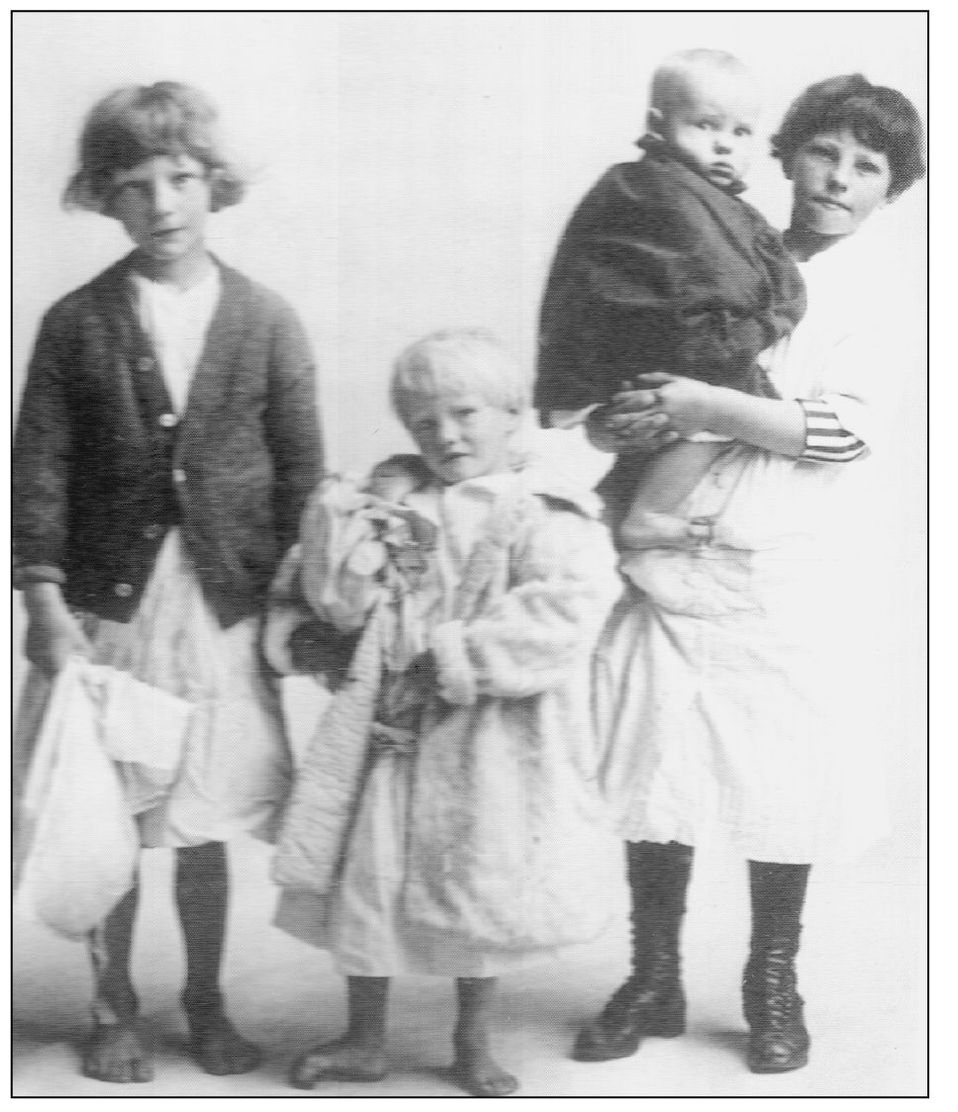

Just married and full of missionary zeal, if few financial resources, the Reverend Harrison Brown and his wife, Libbie, arrived in the Northwest in 1895 determined that the areas orphaned children find homes. A Century of Turning Hope into Reality: A 100 Year Retrospective of Childrens Home Society in Washington State asks, regarding the children in this photograph, Whence came these homeless waifs in the early years? The most common disruptions in childrens lives at the turn of this century were death, desertion, drink, and divorce. (Courtesy Childrens Home Society of Washington.)