In Southern Italy life is reversed; the simplest thing becomes the most complex.

Ann Cornelisen, Torregreca

As you journey south of Naples towards the remote region of Basilicata youll see its monumental, majestic mountains rising ahead of you. Theyre rocky, barren peaks, sometimes capped with snow, a church or a crucifix. The mountains turn an ever fainter blue until, in the distance, they blanch and blend into the wide sky.

Basilicata is the forgotten land of Italy. My dog-eared, twenty-year- old guide book to the peninsula has only six pages, out of over eight hundred, on the region. When I stop in a service station to buy a map of the area, the man behind the counter looks at me with surprise.

Basilicata? he asks gruffly, frowning as if Ive made a mistake. He spins the map stand and pulls out alternatives. Weve got Campania. Theres Calabria, or Sicily. There are dozens of guides to other regions but not one for Basilicata. Its not somewhere that tourists travel to.

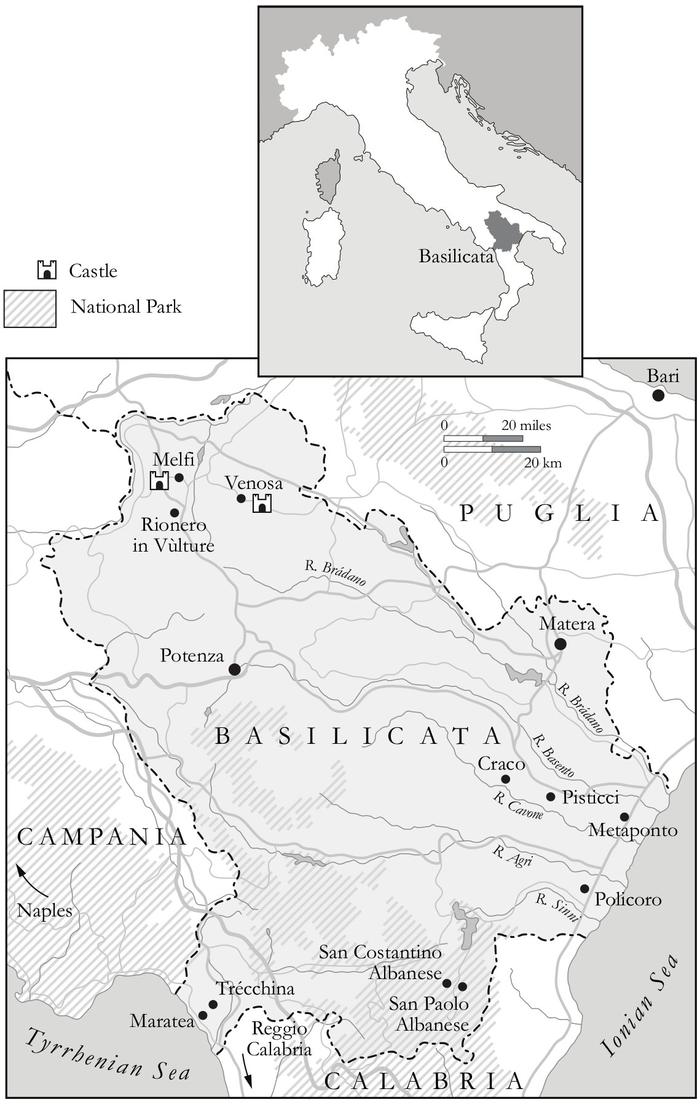

Even most Italians would be hard pushed to say exactly where Basilicata is: it straddles the instep and the metatarsal of the Italian boot, dipping into both the Ionian and Tyrrhenian seas. Its the second most sparsely populated region in Italy after the Valle dAosta, its 10,000 square kilometres containing under 600,000 souls. Ninety two per cent of the region is classified as either mountainous or hilly.

Many people dont even use the name Basilicata. The Romans called the area Lucania, a name revived under Mussolini, and today people still refer to the place as Lucania and to themselves as being Lucani. Theres much debate as to the origin of the word. It derives, possibly, from one of the tribes that settled here, either the Lyki or the Lucani. Others say that it comes from the Greek for brightness, leukos, or from the Latin for forest, lucus, or possibly from the Greek lykos, meaning wolf. When youve spent enough time in Lucania, all of these origins seem plausible. It has a remarkable combination of light and dark, of settled history and sudden danger, of dense forests and open spaces.

Its wetted by two seas, wrote Francesco Saverio Nitti of his homeland in his famous book Heroes and Brigands in 1899, and both one and the other have very melancholy coastlines. It doesnt, he admitted, have blossoming cities or industries. Its countryside is sad and its inhabitants are poor. The title of his book referred to the brigands who had led a ferocious insurgency against the imposition of the Piedmont monarchy in the years immediately after unification. Such was Lucanias distance from the centres of power Rome, Milan, Turin that men like Carmine Crocco became folk heroes for their resistance to the northerners and the Piemontesi. More than a century after that era of brigantaggio, Lucania was still sufficiently remote that it was the perfect place to hide the kidnapped John Paul Getty III in the 1970s.

That remoteness was also the reason for Mussolini sending political opponents of his regime to Lucania (he called it, after all, the most forgotten land). Intellectuals like Carlo Levi or mafiosi like Calogero Vizzini ended up exiled here in the 1930s, the former writing the most famous book ever published on the region, Christ Stopped at Eboli. It was during his exile that Levi met the dogged, endearing peasants living in a land hedged in by custom and sorrow , cut off from history and the State, eternally patient a land without comfort or solace, where the peasant lives out his motionless civilization on barren ground in remote poverty, and in the presence of death.

This shadowy land, he noted, was almost exiled from time; the cemetery was perhaps the least melancholy spot in the village. Levi wrote about the gloomy resignation and primitive solemnity, noticing the tragic beauty of the place and the mountain-top houses that appeared to teeter over the abyss. Long after he left, there were still people in Lucania living, literally, in caves, in the famous sassi of Matera. Theres something primitive and timeless about this backdrop. Its not surprising that this lonely land, with its rocky, rugged mountains, was where Mel Gibson chose to film The Passion of the Christ.

Even today its a place that often appears untouched by modernity . Youll see old women bent double in the fields, scarves protecting their heads from the insistent sun as they slowly hoe the dusty soil. Some of the mountain villages are so isolated that the inhabitants still speak Albanian. There are almost no railways. The signs you see most often as youre driving are strada con buche, road with holes, or else strada dissestata, meaning uneven road. Its a part of the world that feels primitive and elemental. Its a region of such hardship that between 1875 and 2006 almost a quarter of a million people emigrated. Set against that barren backdrop, human life seems somehow surprising and unexpected, almost incidental. The most common thing people say to you is Qui nun g niend: Theres nothing here.

Thats not quite true, of course. There are, in every village and town, fascinating glimpses into the history of the peninsula. The food and, especially, the wine are wonderful. There are many sites of astonishing natural beauty: wild places that, for once, seem untamed and untouched by human greed. And, in many ways, the region is actually thoroughly modern. There are wind turbines on some of those majestic mountains. Oil has been discovered in the region, meaning that huge pipelines run parallel to some of the dual carriageways. People talk optimistically of Lucania as the Texas of Italy. There are large industrial plants, trunk roads, occasional riches. This is where Italys largest telescope is to be found. Many of the sofas in Europe are made in Matera.

But none of that explains why it is that Ive become so attached to Lucania. I dont even know how it happened, but this, of all the places in Italy, feels like my spiritual home. Theres something here that, a long time ago, just got under my skin. Its more a question of the people than the place. Perhaps because its an area almost entirely untouched by tourism, the Lucani are extraordinarily hospitable and generous. If you ask directions of someone, theyll invariably walk you there themselves, stopping on the way in their cousins bar to offer you a coffee. Offro io Ill pay is one of the most common phrases you hear. They often seem both astonished and delighted that a foreigner should come to this forgotten land, and are always eager to share the treasures of their region.

And, I discovered, there are many treasures, most of all the Lucani themselves. When I first moved to Italy in the late 1990s, I lived with three young men from Matera. It was, to say the least, a baptism of fire. They would have ferocious arguments and then, seemingly without reason, they would be laughing and joking together as if nothing had happened. They spoke a dialect that was incomprehensible to me. Lunch was rarely before three and dinner was always well after dark, normally at nine or ten. There was something about their impetuousness, about their pride in the land they had left behind, something about their passion and humour that intrigued me.

I remember being told by one of them that Lucania produced the best bread in the world. I sat there for over an hour, gently trying to suggest that Genoa, or France, or Germany, or God forbid even Britain produced some pretty decent loaves, but he was having none of it and got increasingly irate as he realised I wouldnt be persuaded that, in the whole world, only Lucania produced the perfect loaf.