Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

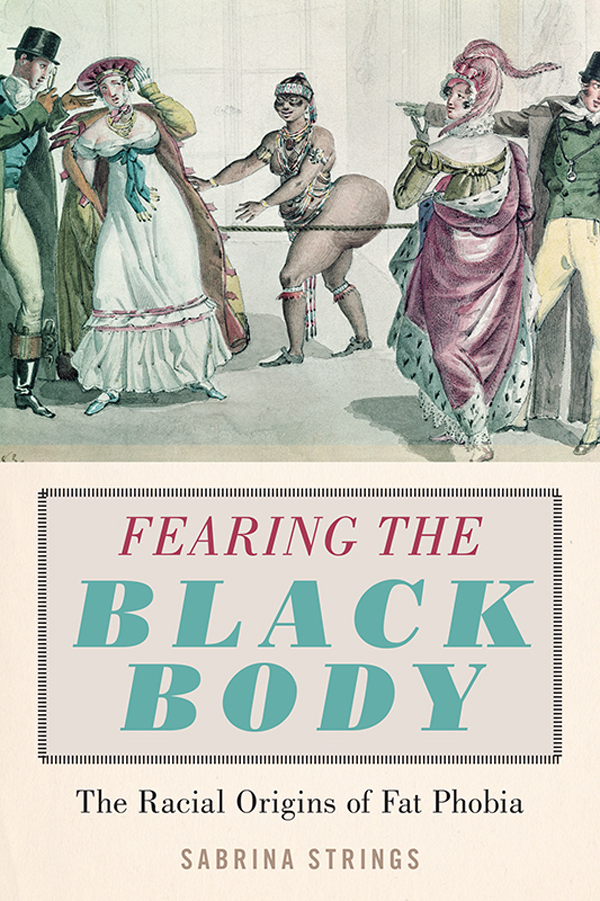

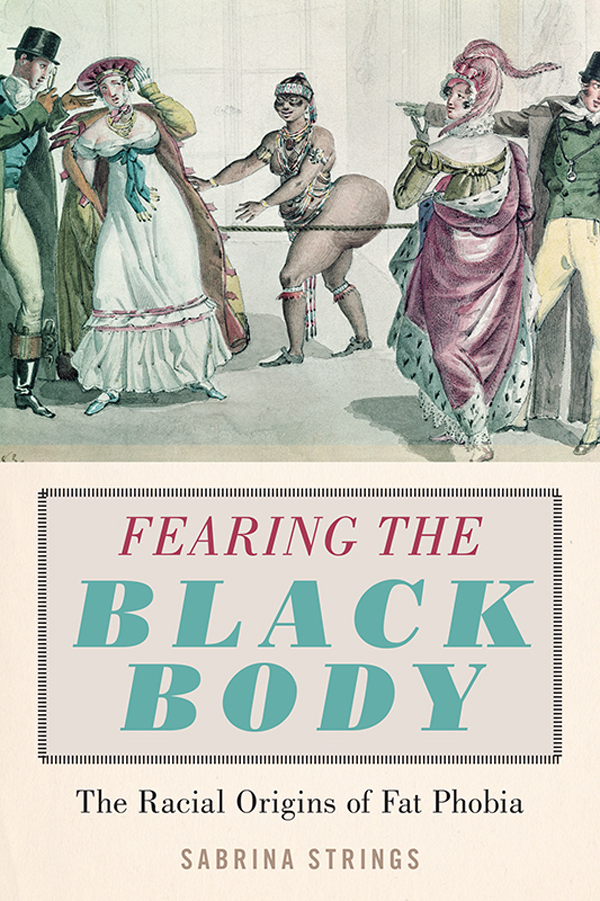

FEARING THE BLACK BODY

Fearing the Black Body

The Racial Origins of Fat Phobia

Sabrina Strings

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS

New York

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS

New York

www.nyupress.org

2019 by New York University

All rights reserved

References to Internet websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor New York University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Strings, Sabrina, author.

Title: Fearing the black body : the racial origins of fat phobia / Sabrina Strings.

Description: New York, NY : New York University Press, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018026988| ISBN 9781479819805 (cl : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781479886753 (pb : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Feminine beauty (Aesthetics)Social aspectsUnited States. | African American womenSocial conditions. | Overweight womenUnited StatesSocial conditions. | ObesitySocial aspectsUnited States.

Classification: LCC HQ 1220. U 5 S 77 2019 | DDC 305.48/896073dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018026988

New York University Press books are printed on acid-free paper, and their binding materials are chosen for strength and durability. We strive to use environmentally responsible suppliers and materials to the greatest extent possible in publishing our books.

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Also available as an ebook

For my grandmother Alma Jean Green

CONTENTS

Introduction

The Original Epidemic

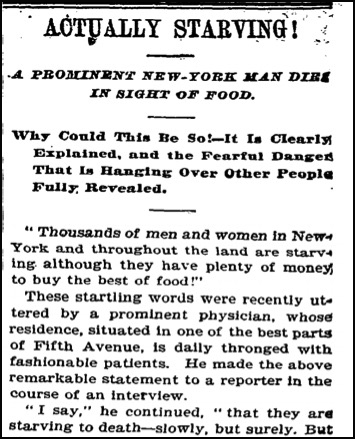

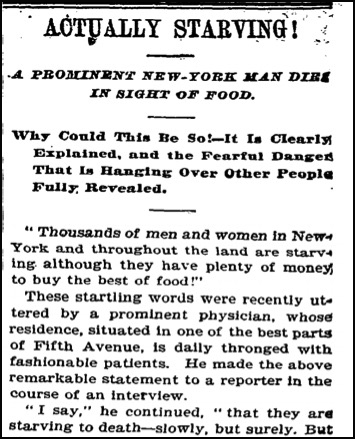

Actually Starving! A Prominent New York Man Dies in Sight of Food. Why Could This Be So! This dramatic if slightly awkward headline appeared in the February 16, 1894, edition of the New York Times , atop an article that began, Thousands of men and women in New York are starving, although they have plenty of money to buy the best food!

The unnamed author of the article went on to quote what was described as a prominent physician on the state of the American diet and physique. According to the doctor, the situation was dire. I say that they are starving to deathslowly, but surely, he stated, adding that although many of those afflicted were members of the middle and upper classes, they nevertheless looked emaciated [and] appear to be consumptives.

This article underscored the deep anxiety felt by many in the nineteenth-century regarding the state of the American physique. Doctors in particular agonized over what they described as the pale, thin, and puny forms that were apparently proliferating around the country. Several described with horror the narrow chests, and lank limbs, and flabby muscles, and tottering steps [that] meet us at every corner. Thinness, it seems, was nothing short of an epidemic.

If in those years slenderness was considered a general American failing, the paleness, leanness, and malnutrition of women was particularly troubling. Prompted by the fragile state of their bodies, esteemed doctors wrote disquieting manifestos on the question of their frailty.

The writings of the prolific and well-regarded New Englander Dr. William Alcott, a distant relative of the novelist Louisa May Alcott, were typical. In his 1855 treatise The Young Womans Book of Health , Alcott lamented the reality that our children, females among the rest, are trained by a community which is thus destitute of a true appetite.

Figure I.1. Actually Starving, New York Times , Feb. 16, 1894.

Dr. John Harvey Kellogg, the famed Seventh-day Adventist already known for his sanitarium in Battle Creek, Michigan, but not yet known as a purveyor of breakfast cereals, concluded in his Ladies Guide in Health and Disease , Particularly in this country, and especially in the cities and towns, girls as a rule are found to be decidedly lacking in physical development.

It was more than a simple question of health or even aesthetics. The slenderness of American girls was regarded as nothing less than a threat to the nation. An 1888 article from the Washington Post that appeared under the headline Are Girls Growing Smaller? exclaimed, The girl of the period ranges from 140 pounds down in some cases to 80 pounds or less. In England and Germany the figures are higher. Eighty pounds of femininity is of course, not much. And, the writer added, our women will go on getting thinner and thinner until they disappear. It has happened in Boston already. The American stock cant hold its own against the big-boned strong-built foreigner. The Irish have crowded the Yankee out of New England.

The weight of American women represented, to many, a national black eye. But was it truly the case, as was often suggested, that these women were simply nutritionally uninformed? Given the right information, would they gain in flesh and, by proxy, in health, strength, and beauty?

The evidence suggests otherwise. Many well-to-do women it seems were trying to be slender at a moment when doctors routinely attacked slenderness as unhealthy. The svelte style, being contrary to conventional medical wisdom, had clearly been motivated by other factors.

Indeed, while many considered thinness an American shortcoming, for the adherents of the style, slenderness served as a marker of moral, racial, and national superiority. This attitude is on full dsiplay in an 1896 article from Harpers Bazaar titled Are Our Women Scrawny? It begins with a reflection on the slenderness of American women: American women in general are still thought to be sallow and scrawny. The articles anonymous author contests this assertion, claiming that while poorer women may be malnourished, few women of the privileged classes are so slim as to look peaked, as may have been the case with their foremothers. Today, the author asserts, American women have a wholesome glow in their cheek and a bit more flesh on their bones, both of which are a testament to the wholly unmeasured success of the American experiment.

Yet, while praising a new and laudable roundness to the figure of the modern girl, the author nevertheless betrays a preference for traditional American slenderness. Of the shifting outlines of the nations women, the author wrote, One cannot help noticing in every metropolitan assembly that the feminine litheness and flexibility for which the republic has been famous is already on the wane, and that the opposite extreme is menacing.

Figure I.2. Are Our Women Scrawny?, Harpers Bazaar , Nov. 1896.

That fatness is described as menacing is telling. The author provides a sense of the foreboding associated with excess weight. Not only does stoutness supposedly sabotage the nations aesthetic identity, it also evokes the poor eating habits and immorality of the European elite. Worse still, extreme or gross corpulence slides into an association with primitive Africans. The author spells this out for the reader: Stoutness, corpulence, and surplusage of flesh are never desirable except among African savages.