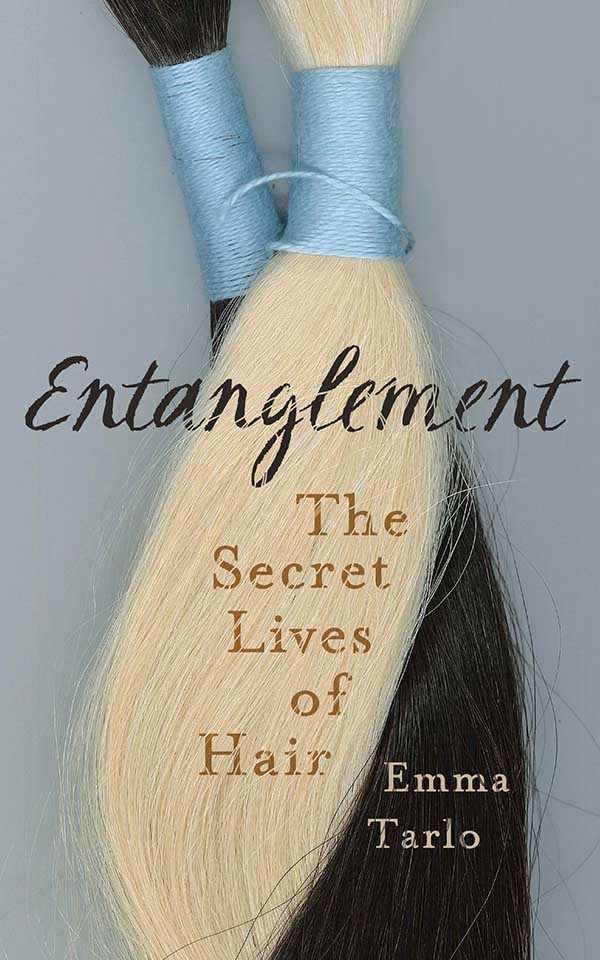

Entanglement

In Entanglement Tarlo opens up a whole secret world of human hair, its diverse social meanings across cultures and the robust trade of it that has carried on for centuries across the world. She weaves in historical details that address issues of religion, symbolism, fashion and economy, and presents ethnographic encounters with a range of characters from Dakar to Wenzhou, Chennai to New York millionaire wig dealers, impoverished villagers sorting comb waste, temple officials and fashionable women who all perform an important role in this ubiquitous but unseen trade. This book is for everybody who is curious about how a single object can become a sought after commodity around the globe. Entanglement is beautifully written and while based on rigorous academic research it eschews jargon and makes the fascinating story of hair the centrepiece of the narrative. A most rewarding and edifying read.

Mukulika Banerjee, anthropologist, London School of Economics and Political Science

A timely book that takes a fascinating journey through the business practices and politics of hair, and the questionable relationship between hair dealers, middle-men and the consumer.

Professor Caroline Cox, author of How to be Adored

This is a book about the only crop we routinely harvest from our own bodies hair. From that disconnection come amazing tales: histories of paupers and pedlars in Europe, vast global trades in wigs, poignant stories of chemotherapy and memorialisation. Also problematic reconnections Orthodox Jews discover their wigs are made from hair presented to Hindu temples. As ethnographer and traveller, Emma Tarlo observes much of this first-hand. Ultimately, she has done an extraordinary job of reattaching hair to humanity.

Daniel Miller, professor of anthropology, University College London, and author of Stuff and The Comfort of Things

Entanglement

The Secret Lives of Hair

Emma Tarlo

For my parents, Helen and Len

who taught me the art of listening

and for the anonymous untanglers of comb

waste whose voices are rarely heard

Strange Gifts

Eeva hands over her hair quite matter-of-factly in a transparent plastic bag. A flaxen plait, irresistibly silky and elegantly coiled, reminiscent of a Victorian love token. I feel it should be tied in lace ribbon, swinging down the back of a young girl in a full-length, high-collared tartan dress, or at least mounted respectfully on a puffed cushion of crimson velvet set off by a gilded frame. Instead it lies stark naked, gazing coldly at me through the plastic, like one of those goldfish you win at fairs. I find myself stuffing it quickly into the depths of my shoulder bag as if hiding something indecent. Later, when we sit down for lunch in the caf of the British Library, I feel it nagging to be released. I let it out of the bag and stroke it with the reverence it deserves, but something feels wrong. I am caressing the disembodied hair of my friend and she is sitting opposite me, full bodied, tucking into chicken and vegetable soup. Eeva arrived from Helsinki two days earlier with the hair tucked neatly in her suitcase. She seems reconciled to the idea that it is no longer part of her. I am looking at the remaining crop that stops too abruptly at her chin, aware that in my hand I hold what was once its continuation. I cant help mentally reattaching the plait. It snakes over her shoulder and clings possessively to her left breast.

When we part I ask her if shed like to say goodbye to her hair. No, she replies. Ive photographed it on my mobile but I would like to know what they end up doing with it in China. I tell her that at the Hair Embroidery Institute in Wenzhou it will probably end up in the portrait of a world leader. Fine, she replies, but just tell them, not Putin! Then she disappears through the double doors of the reading room.

I too was planning to work in one of the reading rooms of the British Library this afternoon but I am stalled by the cloakroom attendant, who asks me if I have anything valuable in my bag just as Im about to hand it over.

I hesitate.

Black gold is what traders call hair in India, but this is gold gold, which is far more difficult to procure and fetches top prices in todays thriving global market for human hair. Virgin gold is what Russian and Ukrainian dealers would call it, referring not to the purity and lifestyle of the grower but to the claim that the hair has not been chemically treated. In this case, the claim is true. Furthermore this is remy hair, meaning that it has been cut in such a way that the cuticles remain slanted in the same direction from root to point, as they say in the wig trade. Cuticles are flat cells which are arranged along the hair shaft like the overlapping scales on a fish. When they are aligned the hair is less prone to tangling, making it suitable for use in top-quality wigs and hair extensions.

I like to think I am valuing my flaxen charge in purely human terms. It is, after all, imbued with the aura and presence of Eeva. We met in 1998 when we joined the same university department and have shared many experiences since. I have seen her silken mane gracefully swept back and bedecked with flowers on her wedding day, when she exuded an icy beauty in a peppermint green silk dress. I dont want to risk handing over my treasure to a cloakroom attendant. Neither do I want to be found with it in my bag. I am too aware of the strangeness of its presence. Right now I have a burning desire to get it home, where I can take it out and examine it in peace and quiet without feeling like a shady dealer or a hair fetishist caught out in public.

Soon I am cycling through London, my bag safely nestled in a sturdy bicycle basket, the straps wound around the handlebars just in case. But despite my sense of purpose I am easily distracted. How useful it would be if I could just pick up a few things on the way home some steak, a box of cat food, fruit, bagels, flowers. Out of habit I refuse the cashiers offer of a plastic carrier bag. Instead I take my shoulder bag, which already contains books, and load it up to bursting point. It is only then that I realise my purchases are crushing down on Eevas plait.

At home I unpack my wares with trepidation. The plait weighs heavily in its plastic bag and has a fleshy pliancy. It is a little ruffled but unharmed. Ironically, it has been protected by the pack of bagels. Bagels get their elasticity from a protein derivative called L-cysteine which until recently was commonly extracted from human hair much of it collected in Asia and exported to major manufacturing plants in Germany, Japan and China. The hair most commonly used was mens short clippings gathered from barber shops in China and temples in India. Such hair is not long enough for the more lucrative wig and extension industry. derived from human hair and duck feathers for use in foodstuffs even if the country banned its use in soy sauce in 2004, following exposure of the practice on China Central Television.

The story of L-cysteine takes us into the murky area of the relationship between legislation and practice and the problems of traceability in the global economy. What is certain, however, is that Indian dealers are finding it increasingly difficult to shift their swelling stocks of waste hair clippings. Eevas flaxen plait occupies the other end of the hair hierarchy. It is more likely to find its way onto the heads of New York socialites than into their bagels or face creams.

I notice that the cats are beginning to show an unhealthy interest in the packet of hair that is sitting on the kitchen table. I feed them before heading to my study. There I take down two bunches of thick brown wavy hair from the noticeboard above my desk. They have been expertly twined around a cord and looped at the top. This hair until recently belonged to a friend of my mothers, whom we have always called Ann P. Ann P. is now in her eighties but she had kept these bunches since 1949. She handed them over to me in a Marks & Spencer cool bag, which at least offered privacy and comfort.