All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form without the prior written permission of the publisher.

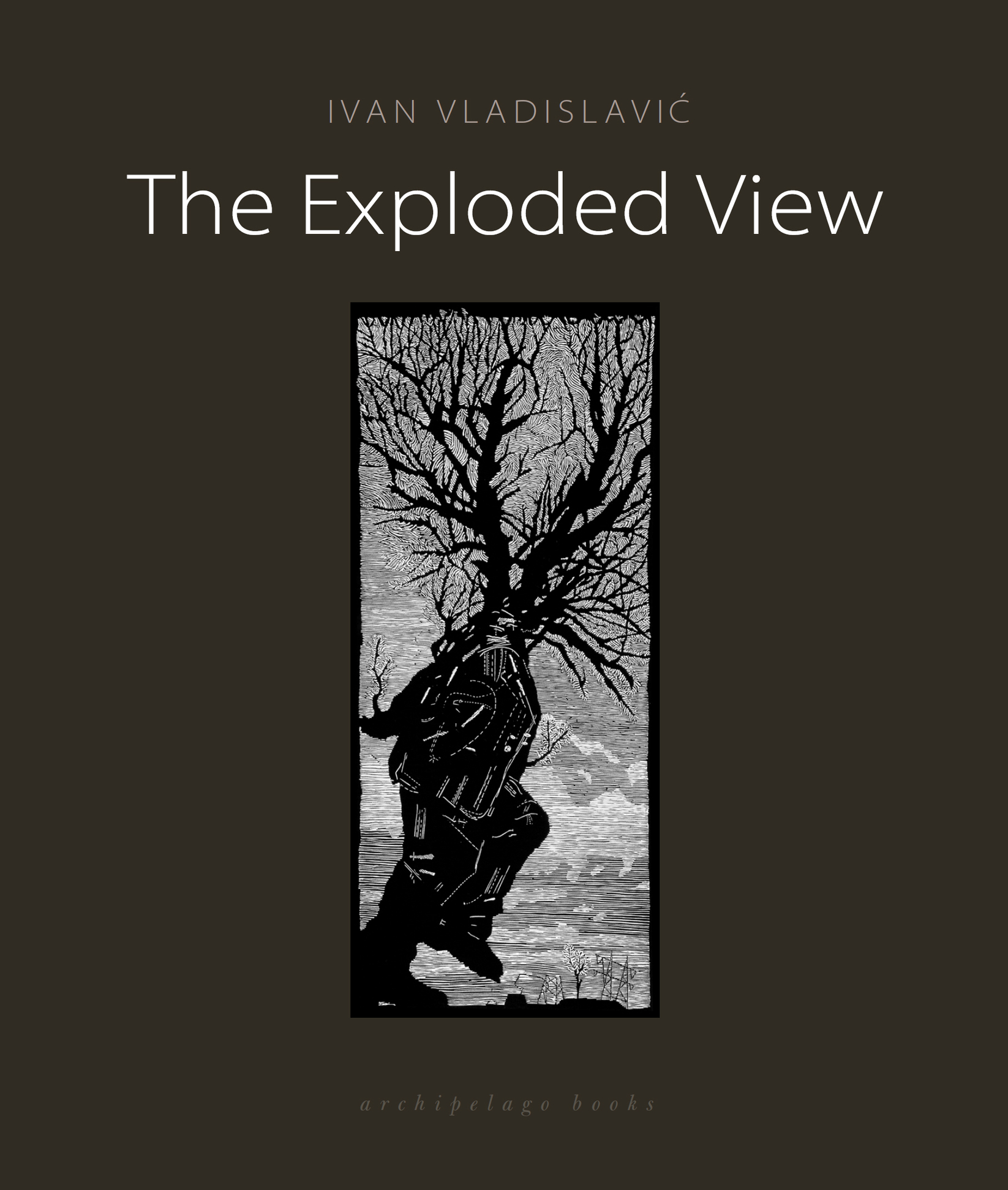

The Exploded View / Ivan Vladislavi.

VILLA TOSCANA

Villa Toscana lies on a sloping ridge beside the freeway, a little prefabricated Italy in the veld, resting on a firebreak of red earth like a toy town on a picnic blanket. It makes everything around the corrugated-iron roofs of the old farmhouses on the neighbouring plots, the doddering windmills, the bluegums look out of place.

Passing by on the N3, Budlender fancied that he could see Iris at one of the windows in Villa Toscana, watching for him. This was his fifth trip to Tuscany. It turned out to be the last, and so brief it was not even filed away under its own name.

He took the Marlboro Road off-ramp. As he waited at the robot, a vendor thrust a bird into the car, some sort of sock puppet with a stiff comb and a scarlet tongue flickering in its throat. Through the stretchy fabric he saw the mans fist flexing to make the tongue pop. Perhaps it was a snake? He wound up the window and glared at the curio-sellers and their wares, ranged on the verges and traffic islands: a herd of wooden giraffes as tall as men, drums and masks, beaded lapel badges promoting Aids awareness and the national flag, fruitbowls and tie-racks and candelabra made of twisted wire. Arts and crafts. Junk. Every street corner in Johannesburg was turning into a flea market. Informal sector employment (as a percentage of the total): 30 per cent. More?

A man holding a hand-lettered sign asking for money or food came closer between the two lanes of cars, moving from window to window and tapdancing for each driver in turn. The smile on his face flared and faded. He was like a toy you could switch off with a shake of your head. At the bottom of the sign was a message: Please drive carefully.

Budlender tilted his head so that the crack in his windscreen, a sunburst of the kind made by a bullet, centred on the vendors body and broke him into pieces.

Was he a Nigerian? It was time to learn the signs. A friend of his at the Bank had given him a crash course in ethnography one evening after work, over a pint at the Baron and Farrier on the Old Joburg Road. He and Warren had sat in a booth, speaking softly, as if the topic were shameful, and then laughing raucously when they realized what they were doing. Small ears? Thats what I said. Little ears, flat against the skull and delicate, like a hamster. And the point of the exercise? Since he had been made aware of the characteristics a particular curl to the hair or shade to the skin, the angle of a cheekbone or jawline, the ridge of a lip, the slant of an eye, the size of an ear it seemed to him that there were Nigerians everywhere. He had started to see Mozambicans too, and Somalis. It was the opposite of the old stereotype: they all looked different to him. Foreigners on every side. Could the aliens have outstripped the indigenes? Was it possible? There were no reliable statistics.

At this point in his career, Budlender had been obliged to combine a passion for statistics, if one could call it that, with a professional interest in immigration. Seconded from the Development Bank by Statistical Services, he was helping to redraft the questionnaires for the national census those used in the census of 1996, the first non-racial headcount in the countrys history, had flummoxed half the population. To make sure that the new versions spoke to everyone, as the brief put it, the drafters had engaged a group of respondents, people with diverse backgrounds (they tried to avoid the old categories of race and population group) and in every income bracket (they steered clear, too, of rich and poor). For months now, he had been shuttling between the Documents Committee and his share of the sample, finetuning questions, ferrying revised drafts to and fro. Driving, always driving.

It was the questionnaire that had brought him to Tuscany in the first place.

The boundaries of Johannesburg are drifting away, sliding over pristine ridges and valleys, lodging in tenuous places, slipping again. At its edges, where the city fades momentarily into the veld, unimaginable new atmospheres evolve. A strange sensation had come over him when he first drew up at the gates of Villa Toscana, a dreamlike blend of familiarity and displacement.

Villa Toscana.

Everything would be filed later. For now, he was like a man in a film who has lost his memory and returns by chance to a well-loved place. Some significant fact, dropped like a matchstick in the back of his mind, kept sputtering, threatening to ignite.

The architect had given the entrance the medieval treatment. Railway sleepers beneath the wheels of the car made the driveway rumble like a drawbridge, the wooden gates were heavy and dark, and studded with bolts and hinges, there were iron grilles in drystone walls. A security man gazed at him through an embrasure in a fortified guardhouse, and then, satisfied that he posed no immediate threat, stepped out with a clipboard.

Budlender opened his diary on the passenger seat to check the name of the respondent.

What number is Miss Iris du Plooy?

Unit 24.

There was a pen tied to the clipboard with a length of string, and on the end of it was a little graven image. He twirled the pen to examine it from all sides. A three-headed animal with a shock of orange hair on the crown of its head, six floppy ears and three pink noses. Canine. The noses were erasers.