.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

AUTHORS NOTE

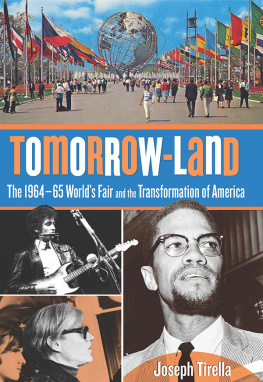

The trouble with intellectuals is that they dont know what a Worlds Fair is all about, wrote George R. Leighton in Harpers Magazine. A Worlds Fair is an art form, a combination of beauty and bombast and the universal hankering for a holiday.

Mr. Leighton visited the 1939 New York Worlds Fair, and later the 1964 version, and sums up one of the most important questions this book attempts to answer: What makes a Worlds Fair a successmoney or love? Theres something enduringly magical about a World of Tomorrow built on an ash heap and poised directly between two of the most catastrophic, and self-defining, events in twentieth-century American history: the Great Depression and World War II. No matter the cost, the result was a promise that life would soon be brighter, easier, and filled with more leisure time than anyone had ever known. And in that way the World of Tomorrow looked hopeful to a degree that it hasnt ever since.

This book came about as the result of an accidental finding one day as I was strolling around the grounds of Flushing MeadowsCorona Park, the site of both the 39 and 64 Worlds Fairs. There, buried in the ground outside of the only remaining building from the 1939 Fair (which now houses the Queens Museum of Art), is a historical marker detailing the events of July 4, 1940. And yet, of the numerous visitors to the Fair that I spoke to, no one remembered anything about it. Several of them assured me that I must be mistaken.

But its true. In fact, every detail of this book is nonfiction; all of the quotes come from a letter, speech, or other documented source, and I have cited as many facts as seems reasonable without going overboard. Theres a temptation in research to footnote every sentence. But thats impossible and, I feel, unnecessary. You cant write history without filling in the blanks or youll leave a lot of blanks. For advice, I turned to a former professor, a true mentor and noted historian, Edward Chalfant. In the first of his three-volume biography of Henry Adams, he offers this perfect summation of the process:

What the biographer does is tirelessly imagine story after story until a story comes to mind which is in every respect sustained and in no respect undermined by all the available evidence, precisely understood. Then the biographer tells that story.

That is what I have done in this book. If there are nagging questions that arise in the readers mind: How does he know what Grover Whalens mood was?, suffice it to say that the answer lies in the body of evidence as a whole. That is, if attendance at the Fair was below expectation, I find it justified to state that its president was worried. The minutes of the Fair Corporations board meetings support that assumption.

In any case the reader can rest assured that I have analyzed the research, have documented as much as possible, and then taken a step back and filled in the pieces where necessary. To my knowledge, those pieces are as accurate, and as few, as possible.

PROLOGUE

This Brief

PARADISE

A worlds fair is its own excuse. It is a brief and transitory paradise, born to delight mankind and die. International expositions do not prevent wars; they go on despite wars. They dont solve the problems of depression and unemployment; they persist in the face of depressions. The worlds fair idea is tough and durable, and the reason is this: people think theyre just wonderful.

G EORGE R. L EIGHTON ,

Harpers Magazine

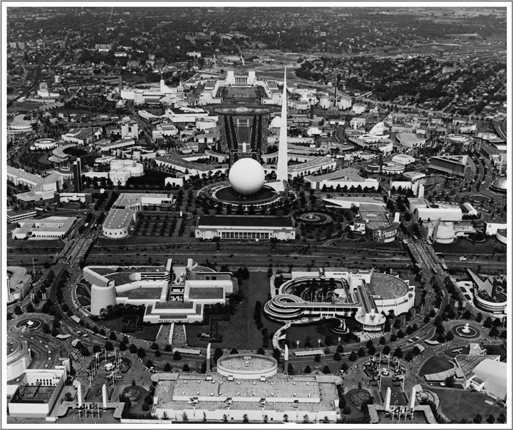

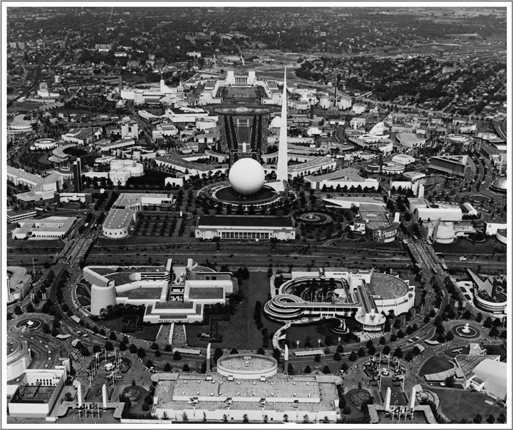

The World of Tomorrow, 1939 (Courtesy of the New York Public Library)

FROM ASH HEAPS TO UTOPIA

O n the Fourth of July 1940, Detective Joe Lynch was enjoying a rare Thursday afternoon at home. Given the current situation, any day off from his frenzied routine with the NYPDs Bomb Squad was a bonus. Ordinarily, on a big holiday like this, he might have treated his family to a picnic out at Rockaway Point Beach. He had his eye on a nice little cottage out there that he hoped to someday buy as a summer retreat for his wife and five children.

But not today. Although he was officially on duty, the department had allowed him to spend the afternoon at home as long as he was available via telephone if something came up. Not that it mattered much; a miserable stretch of rain had been soaking the city for days and pretty much canceled out anyones plans for a summer outing. Despite the weather, Lynch, sitting in his cramped two-bedroom apartment in the Kingsbridge section of the Bronx, listened to the rumble of the elevated train outside his window and thought of the ocean.

This summer especially was not the time for leisurely fun, holiday or no holiday. The second season of the Worlds Fair was in full swing, and every New York City cop knew what it meant to have something so large and so popular going on right in his backyard. There was a tremendous influx of tourists, for one thingmillions of them, if you believed the newspapers. And along with them came the usual cast of characters who cavorting in several shows in the Amusements Area. And that sort of thing couldnt help but promote some inherent desire for an after-hours liaison between spectator and performer.

Lynch knew all this, but he had more pressing concerns on his mind. A Worlds Fair of this magnitude attracted all kinds of agitators who would go to any extreme to make a political statement, especially now that war had broken out in Europe. And it had been just his luck that right before the Fair opened, he and his partner, Freddy Socha, had been assigned to the seemingly dichotomous duties of what was known as the Bomb and Forgery Squad.