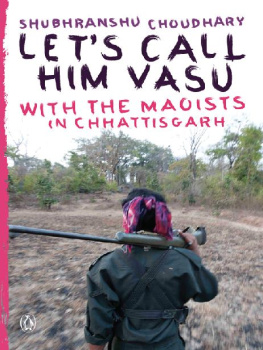

SHUBHRANSHU CHOUDHARY

Lets Call Him Vasu

With The Maoists In Chhattisgarh

PENGUIN BOOKS

Contents

PENGUIN BOOKS

LETS CALL HIM VASU

Shubhranshu Choudhary is a journalist. He has worked for over two decades with media organizations like the BBC and the Guardian . Currently, he devotes his time to an experiment to create a model for democratic media. In the process, he has created the worlds first community radio on the mobile phone called CGnet Swara.

For the Adivasis of Dandakaranya,

who have suffered so much

Prologue

Lets call him Vasu.

He was my first Maoist contact. A dark, stocky young man who spoke Hindi with a Hyderabadi accent, he was introduced to me as a student. Vasu was new to the small town where I worked as a trainee journalist for a newspaper. In a spirit of casual friendliness, I invited him to join me at the Indian Coffee House, where I used to hang around on Sunday mornings.

Vasu never missed a Sunday. He was a serious, well-read young man who spoke knowledgeably on Marxism, and often he would recommend books to me. Ignoring my less than enthusiastic response, Vasu brought a couple of heavy-looking volumes to my room one day.

You know my schedule, Vasu, I told him. I start work at 10 a.m. with the morning meeting, and by the time I go to bed after the paper goes to press, it is 4 a.m.

He only smiled, and promised to return. To my embarrassment, he did, before I had had a chance to open the books he left for me. Vasu was clearly made of sterner stuff than I had foreseen.

I will come to read you a few pages every morning, when you wake up, he insisted.

I gave in to him only because I felt that as a journalist, I ought to be open to whatever came my way. From then on, I found myself being woken up to the unmusical bell of Vasus rickety, second-hand bicycle. Often, he would read Marx aloud to me while I was still in bed.

One day, my room-mate observed that Vasu was remarkably punctual. You can set your watch by his entry, he said.

Indeed, Vasus disciplined approach and commitment were hard to ignore.

And then he added, This Vasu he talks like a Maoist.

I laughed it off as a stray comment at the time, but the remark stayed in my mind.

One morning, when Vasu and I were alone in the room, I ventured a question: I wont ask what your real name is and where you live, but are you a Naxal?

Id used the popular term for underground Maoists, a word that no one would like to be associated with publicly. This was a cue for him to go into fervent denial. But Vasu simply smiled, and nodded in affirmation.

I have been sent to Raipur to develop the Party in urban areas.

I was a little shaken. There were so many journalists to whom I had introduced Vasu, including my room-mate. Why had he chosen to confide in me?

Manendragarh is a small town in the Koriya district of Chhattisgarh. A mining settlement during the British Raj, it was the last stop on a track laid to transport coal. My father had arrived there to work for the Indian Railways. He was from a refugee family who had fled East Pakistan after the Partition. In the classic style of Indias democratic re-colonization, the Indian Railways employed educated middle-class Indians. In independent India, we were the new colonizers of the original inhabitants, the Adivasis. In these undeveloped locations in the heart of India, the Indian Railways built and maintained their own residential quarters. Although there were no fortifications, the class difference between the locals and the transplants was as good as any wall.

It was in this Railway Colony of Manendragarh, typical of its time, that I grew up. I remember the club where we celebrated Durga Puja every yearan imposing colonial building. The ballroom, once frequented by the British sahibs, had been converted into a table-tennis hall. On shelves that had once held bottles of whisky, now rested novels in Indian languages.

I do not remember interacting with the tribals. There was a tribal woman who came home every morning to deliver milk, and a man who tended to our garden on occasion. But we had nothing to do with them socially, even though the school in which I studiedthe only one in townwas run by the tribal welfare department of the state government. The tribal children occupied the back benches of the classroom and lived in a hostel assigned specially to them.

I visited the hostel a couple of times with a classmate, and remember thin, dark children: alien beings who seemed lost in the huge spartan dormitory, laid out with rows of iron cots. Their government-supplied khaki shorts were usually a couple of sizes larger than required. Their crumpled, white, half-sleeved shirts were tight around the armpits, and with their thin chests and stiff shoulders, they looked more like stunted adults than playful children. Though we saw each other every day in class, our lives ran like railway tracks: parallel but always separate.

I did not keep in touch with any of them.

There was no reason to.

My real friends were children of government employees or of local shopkeepers. We were the new Indian middle class, with a voracious appetite for self-advancement: ambitious, not too highly educated, very hard-working individuals who had migrated from various places within the country, and naturally coalesced in and around the new colonies created by the Indian administration. We learned the ropes, built contacts and got well-paid jobs or became mid-level businessmen. We knew exactly how much grease was required at which groove in the machinery to keep the wheels of progress turning. The natural bounty of places like Chhattisgarh provided just the nourishment we demanded.

For the tribals, however, all that had changed was the colour of the sahib.

I do not know why Vasu had chosen me, but as it turned out, I left Raipur a few months after I met him.

By 1990, I had made my way to Delhi. The business of daily news kept me on my toes never visiting the same place twice, hopping from cyclone to earthquake, from civil war to political coup. Soon I began to realize that I had become a vulture journalist.

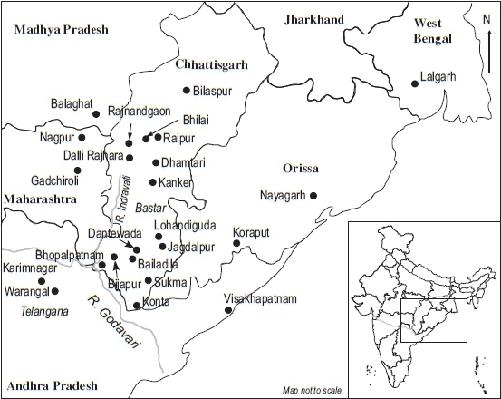

By 2004, having had enough of the carrion, I started to find my way back to Chhattisgarh, where life had begun for me. The quiet, beautiful, thickly forested hills that I had left behind had been carved into a new stateostensibly because of its tribal demography. It had also become, in the words of the Indian prime minister, the epicentre of the gravest threat to Indias internal security.

Over the years, Vasu had kept in touch. Communication between us remained a little odd and always unidirectional. I had learned not to ask him questions that I knew he would not want to answer. It was this tacit understanding that helped us maintain a workable professional relationship. It suited us. Thanks to my job with the BBC, I owned a mobile phone long before they became ubiquitous in India. I could make out from the display on my phone that Vasu called me from a different number each time: clearly, he was using public telephones.