THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN CENTER FOR SOUTH AND SOUTHEAST ASIAN STUDIES

THE MICHIGAN SERIES IN SOUTH AND SOUTHEAST ASIAN LANGUAGES AND LINGUISTICS

Editorial Board

Alton L. Becker

John K. Musgrave

George B. Simmons

Thomas R. Trautmann, chm.

Ann Arbor,

Michigan

INTRODUCTION TO OLD JAVANESE LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE: A KAWI PROSE ANTHOLOGY

Mary S. Zurbuchen

Ann Arbor

Center for South and Southeast Asian Studies

The University of Michigan

1976

The Michigan Series in South and Southeast Asian

Languages and Linguistics, 3

Open access edition funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities/Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program.

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 76-16235

International Standard Book Number: 0-89148-053-6

Copyright

1976

by

Center for South and Southeast Asian Studies

The University of Michigan

Printed in the United States of America

ISBN 978-0-89148-053-2 (paper)

ISBN 978-0-472-12818-1 (ebook)

ISBN 978-0-472-90218-7 (open access)

The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

I made my song a coat

Covered with embroideries

Out of old mythologies.

A Coat

W. B. Yeats

Languages are more to us than systems of thought transference.

They are invisible garments that drape themselves about our spirit and give a predetermined form to all its symbolic expression.

When the expression is of unusual significance,

we call it literature.

Language and Literature

Edward Sapir

Contents

So little of the rich body of Old Javanese (Kawi) literature is available to students of Southeast Asian culture that it seems this thesis has much too small a purpose. A few excerpts from prose works do not succeed in giving a general feeling for the literary tradition of this ancient language. I have chosen only prose selections, however, because the beginning student often has a more rewarding experience with its straightforward style and syntax.

This anthology is intended to be used along with its companion volumes in this series on Old Javanese language and literature. Forthcoming are a detailed grammar of Old Javanese by A. L. Becker and a wordlist, comprising some 13,000 entries, by Soewojo Wojowasito. In the absence of the companion volumes the reader may turn to the reference works on Old Javanese listed in the bibliography. I have emphasized access to systems of meaning here rather than grammatical analysis, and my glossary is hardly a substitute for a more complete dictionary.

I have had much help in preparing this thesis. Visiting professors of Indonesian languages at the University of Michigan, Imam Hanafi, I Gusti Ngurah Oka, Soewojo Wojowasito and Mohammad Icksan, through their work, have contributed greatly to my understanding of the texts. Madhav Deshpande, my Sanskrit professor, has assisted in preparing notes on the Sanskrit fragments. Other persons in Southeast Asian studies have given aid and advice, among them Patricia Henry, Judith Becker, Stanley Hoffman, Susan Walton, Francy Hays and Richard Wallis. Special mention and credit are due to Mark Poffenberger for seeing the whole enterprise through.

Above all, my deep gratitude goes to my teacher and advisor, Alton L. Becker. In his classes, and with his continuing interest, attention, counsel and inspiration, this work has flowered.

The spelling system used here adheres to the Kawi writing system, which includes representations of Sanskrit phonology which were not relevant to Kawi. It is not known how many distinctions were made in ancient pronunciation. Following modern Indonesian pronunciation, however, sounds of Old Javanese are as follows:

| a, | f a ther |

| i, | f ee t |

| u, | m oo n |

| sof a |

| h e r |

| e | p e t |

| ai | m y |

| o | c oa t |

| b, bh | ba b y |

| c, ch ch urch |

| , h , h | re d |

| g, gh | dog |

| h | h ot |

| j , jh | j ury |

| k, kh | li k e |

| 1 | l eave |

| m | m other |

| n, | n oon |

| ng | morni ng |

| ca ny on |

| p, ph | li p |

| r, | bu tt er |

| s, | s oap |

| sh oe |

| t, th , h | ra t |

| w | w ant |

| y | y es |

Following the Sanskrit model, Old Javanese vowels change form when they occur together. The most common changes created by sandhi are as follows:

| a + a = | a + = a |

| a + = | a + i = e |

| + = | a + u = o |

| i + i = | e + = e |

| i + = | i + a = e ya |

| + = | i + = i |

| u + u = | o + a = wa |

| u + = | o+ = |

| + = | + = |

| u + a = wa - o |

| u + = u |

| u + i = wi |

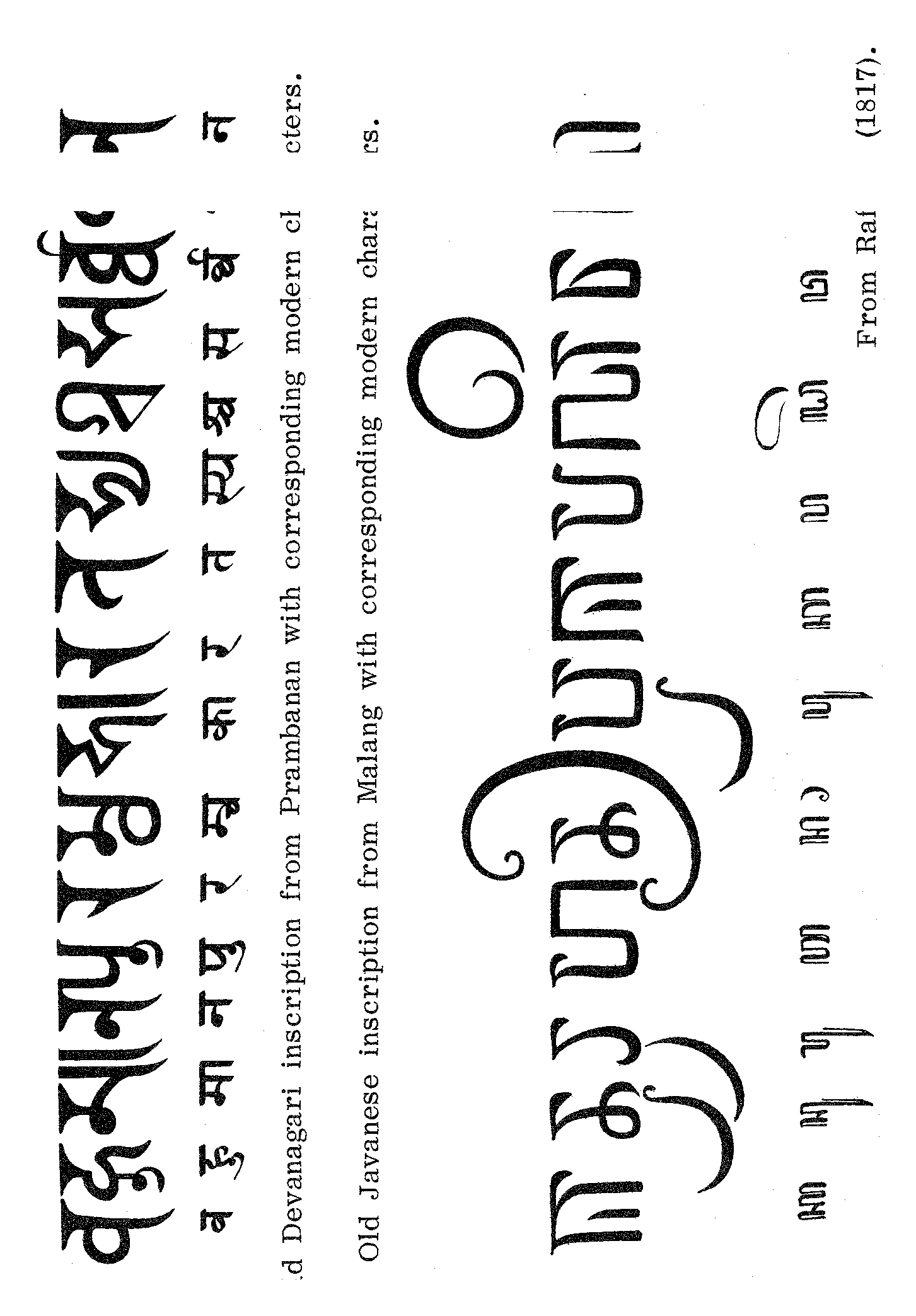

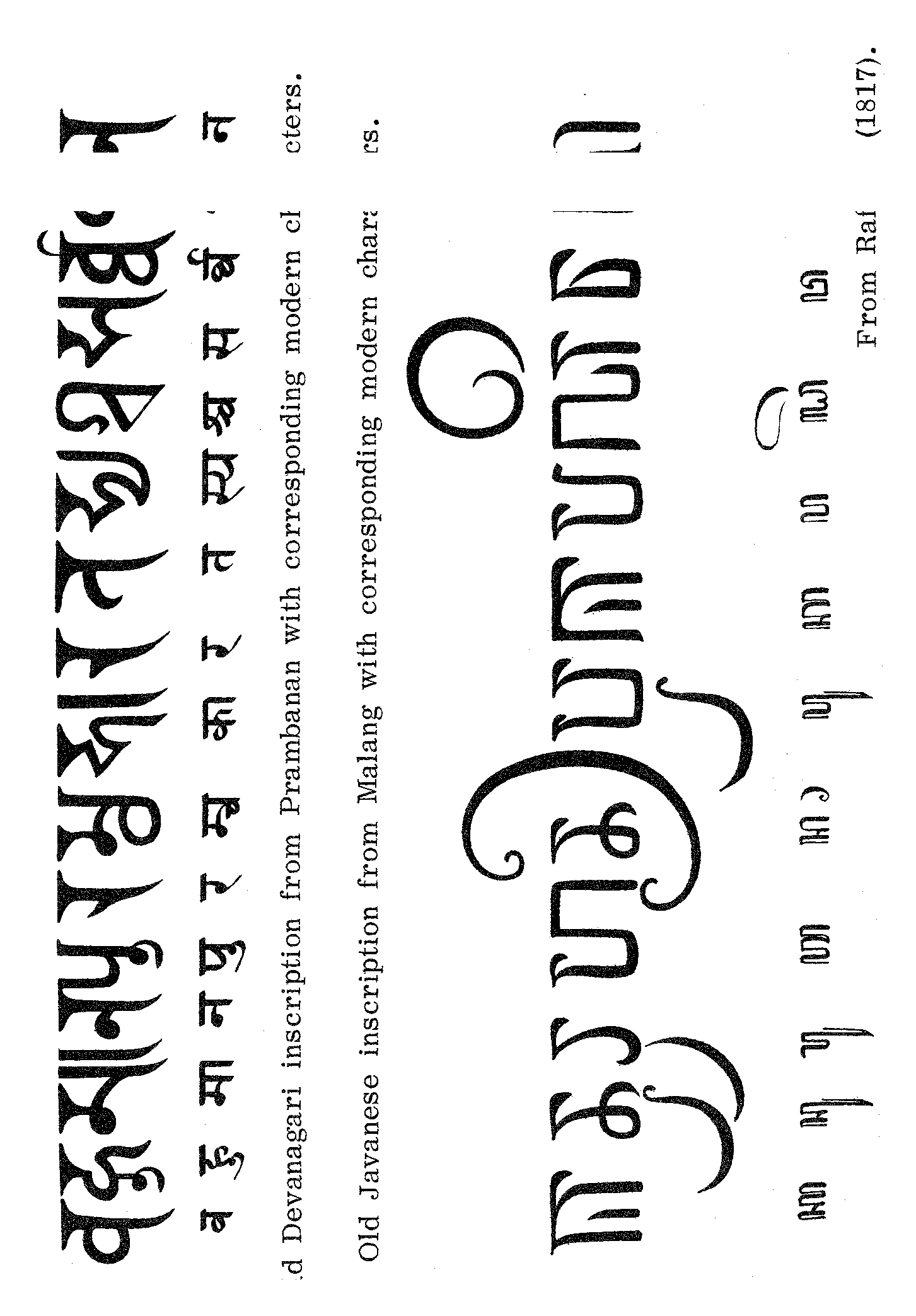

The oldest and most extensive written language of Southeast Asia is Old Javanese, or Kawi. It is the oldest language in terms of written records, and the most extensive in the number and variety of its texts. Relatively few texts are available in English. The unstudied texts remaining are an unexplored record of Javanese culture as well as a language still alive as a literary medium in Bali.

The study of Kawi literature is important for several reasons. Linguistically, Kawi provides the oldest records of Javanese, spoken by over 50 million people in the central and eastern parts of Java. In fact, Old Javanese is the only Malayo-Polynesian language for which ancient documents are extant, with the exception of a few Old Malay inscriptions.

Some form of Kawi was the spoken language of Java in prehistoric times. Our earliest record of its use is the Sukabumi charter, dated 804 A.D. [Zoetmulder (1974:3)] . Older inscriptions or charters in stone and copper plate have been found in Java and Sumatra, but these are all in Sanskrit or Old Malay. Apparently Old Javanese only gradually became the language of official documents, although we can assume its spoken form was the major language of Java long before the ninth century.

The early period of Javanese history is obscure. Little is known of Javas first contacts with Indic traditions. A major center of Hindu and Buddhist learning is known to have existed by the seventh century in the kingdom of riwijaya in southern Sumatra, and the earliest interaction with India must have occurred long before.

At the time of the oldest records in Kawi the major Javanese kingdom was located in the central region of the island. Its rulers were related to the Buddhist kings of riwijaya. The dynasties of central Java left as records of their culture the Hindu monument of Prambanan and the great Buddhist stupa Borobudur. The oldest extant piece of Kawi literature, the Kakawin Rmyaa, is the only work which has been reliably dated from the central Javanese period, prior to 930 A.D. [Zoetmulder (1974:231)] .

The year 930 marks the movement of the court of Siok from central to eastern Java. Under Sioks descendant Dharmawanga Teguh the Old Javanese parwa (books of the Indian epic Mahbhrata) were composed. After an attack in 1016 the kingdom was broken up, to be reunited by the half-Balinese prince Erlangga between 1028 and 1035 [Zoetmulder (1974:244)] . The Kakawin Arjunawiwha dates from Erlanggas time, and contextualizes the kings biography in the epic imagery of the Pandawa hero. Erlangga divided his kingdom between his sons in the mid-eleventh century. The two courts, Janggala and Kairi, were rivals for many years, although the literature of the period seems to have all originated from Kairi, while there are virtually no records of Janggala [Zoetmulder (1974:19)] .