Javanese Gamelan and the West

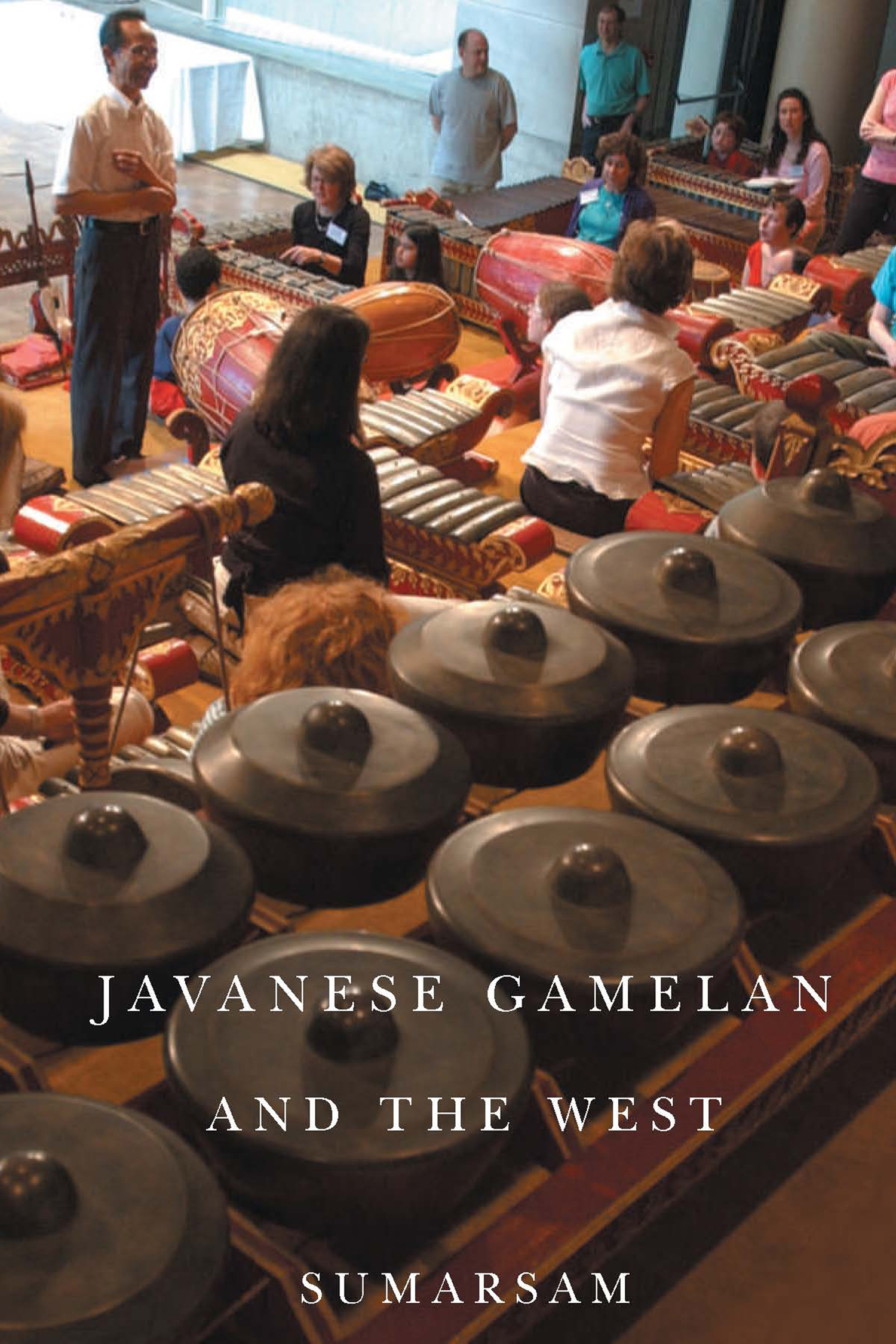

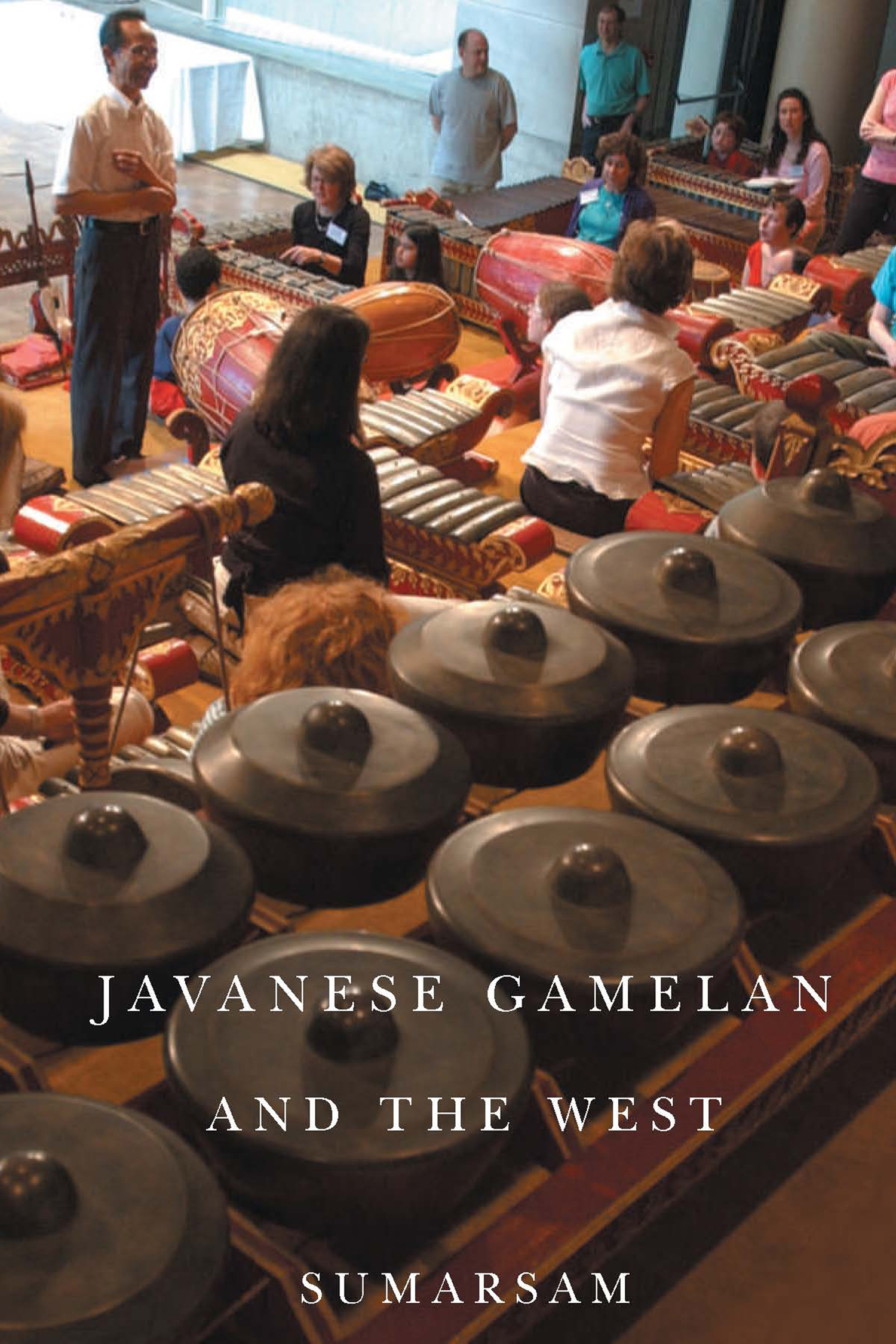

Javanese Gamelan and the West studies the meaning, forms, and traditions of the Javanese performing arts as they developed and changed through their contact with Western culture. Authored by a gamelan performer, teacher, and scholar, the book traces the adaptations in gamelan art as a result of Western colonialism in nineteenth-century Java, showing how Western musical and dramatic practices were domesticated by Javanese performers creating hybrid Javanese-Western art forms, such as with the introduction of brass bands in gendhing mares court music and West Javanese tanjidor , and Western theatrical idioms in contemporary wayang puppet plays. The book also examines the presentation of Javanese gamelan to the West, detailing performances in Worlds Fairs and American academia and considering its influence on Western performing arts and musical and performance studies. The end result is a comprehensive treatment of the formation of modern Javanese gamelan and a fascinating look at how an art form dramatizes changes and developments in a culture.

Sumarsam is a University Professor of Music at Wesleyan University. He is the author of Gamelan: Cultural Interaction and Musical Development in Central Java (University of Chicago Press, 1995) and numerous articles in English and Indonesian. As a gamelan musician and a keen amateur dhalang (puppeteer) of Javanese wayang puppet play, he performs, conducts workshops, and lectures throughout the US, Australia, Europe, and Asia.

This book offers a sweeping overview of Javanese musical and cultural interactions with the rest of the world, providing critique and reconsideration of the prevalent themes and ideas that have fascinated scholars for decades. It will be essential reading, not only for Javanists but for scholars of postcolonialism in general. Sarah Weiss, Associate Professor, Department of Music, Yale University.

Eastman/Rochester Studies in Ethnomusicology

Ellen Koskoff, Series Editor

Eastman School of Music

(ISSN: 2161-0290)

Burmas Pop Music Industry:

Creators, Distributors, Censors

Heather MacLachlan

Yorb Music in the Twentieth Century:

Identity, Agency and Performance Practice

Bode Omojola

Javanese Gamelan and the West

Sumarsam

Copyright 2013 by Sumarsam

All rights reserved . Except as permitted under current legislation, no part of this work may be photocopied, stored in a retrieval system, published, performed in public, adapted, broadcast, transmitted, recorded, or reproduced in any form or by any means, without the prior permission of the copyright owner.

First published 2013

University of Rochester Press

Paperback edition published 2015

This edition published 2015

668 Mt. Hope Avenue, Rochester, NY 14620, USA

www.urpress.com

and Boydell & Brewer Limited

PO Box 9, Woodbridge, Suffolk IP12 3DF, UK

www.boydellandbrewer.com

ISBN-13: 978-1-58046-445-1 (Hardback)

ISBN-13: 978-1-58046-523-6 (Paperback)

ISBN-13: 978-1-78204-553-3 (eBook)

ISSN: 2161-0290

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Sumarsam, author.

Javanese gamelan and the West / Sumarsam.

pages cm. (Eastman/Rochester studies in ethnomusicology Volume 3)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-58046-445-1 (hardcover : alkaline paper) 1. Gamelan musicIndonesiaJavaHistory and criticism. 2. Gamelan musicWestern countriesHistory and criticism. I. Title. II. Series: Eastman/Rochester studies in ethnomusicology.

ML3758.I53S86 2013

780.9598'2dc23

2013011376

A catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

What we need to question, then, is not so much hybridity as such, which would be a futile enterprise, but the depoliticization involved in the reduction of hybridity to happy fusion and synthesis. I would argue that it is the ambivalence which is immanent to hybridity that needs to be highlighted, as we also need to examine the specific contexts and conditions in which hybridity operates.

Ien Ang, On Not Speaking Chinese

But was the publics interest in the kampong really anthropological at all? What did the visitors actually see, when they entered the kampong at the exhibitions lessons on the evolution of civilization and colonial superiority? Did they actually connect the explanations in the exposition halls to the world exhibited in the kampong?

Marieke Bloembergen, Colonial Spectacle: The Netherlands and the Dutch East Indies at the World Exhibitions, 18801931

Contents

Examples

Figures

I have been a student, teacher, and performer of gamelan in Indonesia and the United States for most of my life. In the United States, I teach mostly American students, but also those from other countries. I have also been very fortunate to study ethnomusicology at two American universities: Wesleyan in the mid-1970s and Cornell from the mid-1980s to the early 1990s. This cross-pollination of performer-teacher and academic might be the most ideal pursuit in the study of music, but the task has been demanding. Maintaining a balance of time and energy between the two aspects has been a challenge, and at times it has been necessary to prioritize one at the expense of the other.

I came to significantly engage in the world of scholarship quite late, although the seed of my interest can be traced to my years as a student and teacher of gamelan in Indonesia. In 1964, I started teaching at the gamelan conservatory (KOKAR, Konservatori Karawitan Indonesia, now SMK, Sekolah Menengah Kejuruan), a high school of Javanese performing arts. I taught an ensemble, a class on kendhang (drum), and a course on the theory of gamelan playing ( Teori Menabuh ) for first-year students. Conservatory classes were held in the morning, and in the afternoons I was a student at the gamelan academy (ASKI, Akademi Seni Karawitan Indonesia, now ISI, Institut Seni Indonesia). In 1969, I was appointed a part-time assistant to R.L. Martopangrawit, a gamelan teacher and the only gamelan theorist at the academy, work which allowed me to continue my interest in gamelan theory. I published a book on kendhang, containing notations of kendhang with brief commentary. I graduated from the academy in 1968, and subsequently enrolled in a degree equivalent to an MM in the United States, which I never completed; in 1970, I was assigned to join a government performing-arts group performing at the 1970 World Exposition in Osaka, Japan for seven months. After returning to Indonesia for one year, I was assigned to teach gamelan at the Indonesian Embassy in Canberra, Australia. From there, I went to the United States to teach gamelan at Wesleyan University.

After being exposed to the intellectual life at Wesleyan, I was bothered by my failure to complete my degree in Indonesia. In 1974, I enrolled in the MA program in world music at Wesleyan, while continuing to teach gamelan. I completed the degree in 1976, and my continuing interest in academic work led me to embark on a doctoral program at Cornell University in 1983, during my sabbatical leave from Wesleyan. I was already in my late forties when I completed my doctorate in 1992. I feel now that I still have a lot of catching up to do, and writing in a language not my own presents another challenge.

I should mention that in the graduate musicology program at Cornell, students can work with an advisor to design a specific program to suit their interest. Whatever the students area of focus, he or she must take courses in theory, musicology, ethnomusicology, performance, and composition, or courses from other disciplines. I took advantage of this flexibility by designating ethnomusicology as the field of my study, focusing on Indonesian music. Instead of taking classes in musicology or music theory, I took classes in Southeast Asian studies, including a seminar on Indonesian politics and culture and a number of classes on the history of Southeast Asia. This fusion of Southeast Asian studies and ethnomusicology has led me to focus on the study of gamelan in its historical and cultural context. However, I continue to be fascinated with theoretical issues of music as sound structure thanks to my upbringing as a gamelan musician and my early interest in gamelan theory. I devoted the final chapter of my last book to gamelan theory, and readers of the present work will find that again I address gamelan theory in the last chapter, examining the particular way that scholars formulate gamelan theory epistemologically, and seeking to expand this discussion in ways I feel necessary.

Next page