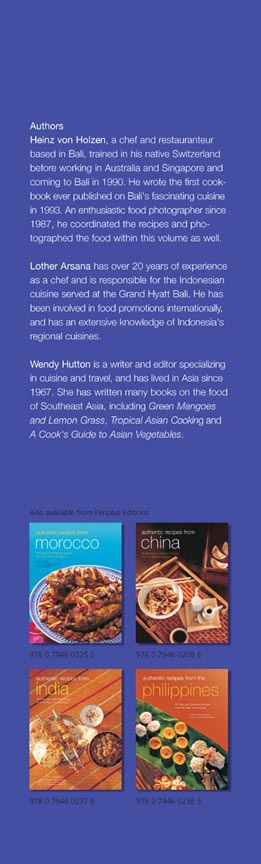

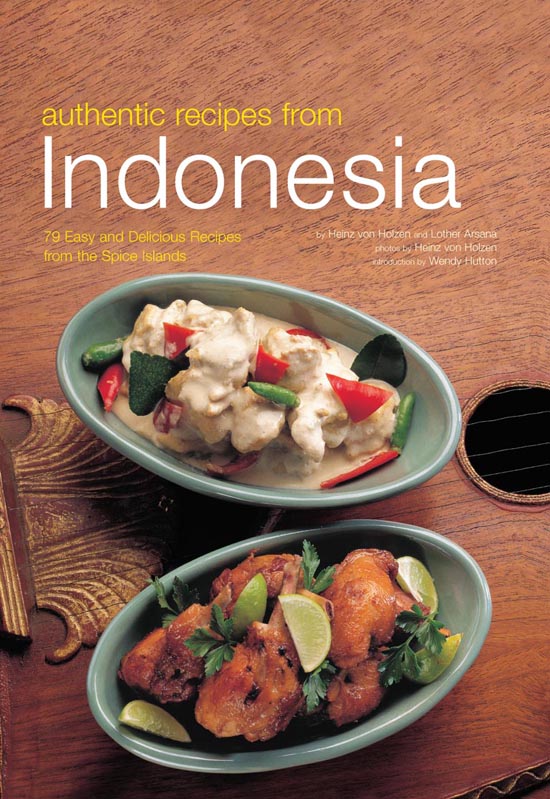

Food in Indonesia

A cuisine as exciting and diverse as the country itself

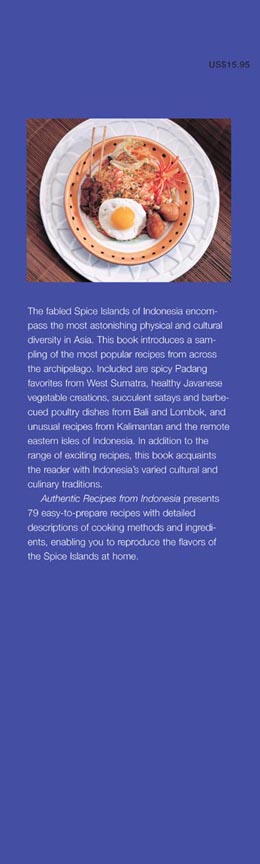

Indonesia is the worlds largest archipelago thousands of tropical islands ranging from some of the worlds largest to mere tiny coral atolls marooned in a sapphire sea. With snow capped mountains and lush rainforests, arid savannahs and irrigated rice fields, its hard to imagine a more appropriate national motto for this nation than Bhinneka Tunggal Ika Unity in Diversity.

Over the past two thousand years, powerful Buddhist, Hindu and Muslim kingdoms rose and fell in Sumatra, Java and Borneo, attracting merchants from as far away as China, the Middle East and India, as well as nearby Siam and Malacca. Some of the archipelagos tiny eastern isles were the original Spice Islands the only places in the world where clove and nutmeg trees grew, and a powerful magnet for traders and pirates.

European explorers and merchants were not far behind. Portuguese, Spanish, English and Dutch ships set forth on voyages of discovery to these islands during the 16th and 17th centuries. The Dutch were the final victors in the battle for control over the region, introducing a plantation system to the main islands, where laborers toiled to produce sugar, spices, rubber, tea and coffee (the original cup of Java). A nationalist movement arose as early as 1908, but it was not until 1949 that the Republic of Indonesia came into being, after an armed struggle against the Dutch following Indonesias declaration of independence in 1945.

With its enormous geographic and cultural diversity, it is not surprising that the food of Indonesia is tremendously varied also. However, as restaurants in Indonesia tend to focus on the dishes served only in Java and Sumatra, many non-Indonesians are unaware that each region actually has its own distinct cuisine. These indigenous regional styles have been influenced to varying degrees over the centuries by ingredients and cooking styles from China, India, Europe and other parts of Asia.

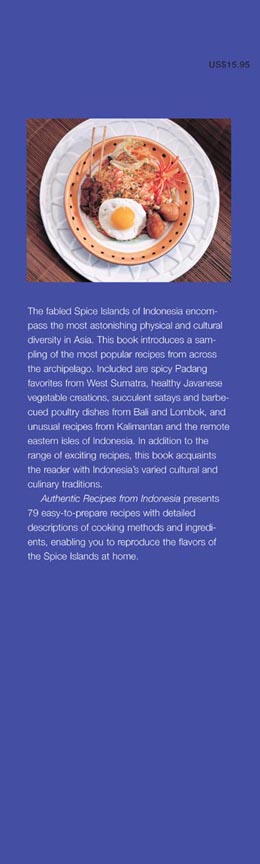

A typical Indonesian meal might be described as a simple mound of rice accompanied by several savory side dishes of vegetable, fish or perhaps a meat or poultry dish, with a chili hot condiment or sambal on the side and peanuts, crispy wafers (krupuk) and fried shallots sprinkled on top to provide a crunchy contrast. While such a description might be valid for much of Java, Sumatra and Bali, in other areas of the archipelago, the staple might be sago, cassava, yams or corn instead of rice.

Increasing numbers of visitors are discovering the rich cultural diversity of Indonesia, venturing off the beaten Bali-Java-Sumatra tourist track. Let us take you on a voyage of culinary discovery, exploring the unknown and revealing more about the already familiar.

Eating your way across the archipelago

What do a feast of pig steamed over hot stones in an earth oven, a ritual centered upon a golden rice mountain blessed by Muslim prayers, a bamboo tube of buffalo meat spiked with chilies roasted over a fire, and satays of minced seafood mixed with spices and fresh coconut all have in common? Theyre just some of the foods I have enjoyed in travels throughout Indonesia over more than two decades. Visitors encountering the limited noodle and nasi goreng fare found in most Indonesian restaurants might be forgiven for thinking that theres more unity than diversity in the food here. Its only if you brave the local warung or simple food stalls (as opposed to those run by migrants offering the ubiquitous soto or mie bakso), if you arrive when a festival is going on or, best of all, are able to stay in Indonesian homes, that you have a chance of discovering the diversity of Indonesias native cuisines.

Some 3,200 feet (1,000 meters) up in the highlands of Irian Jaya, in western New Guinea, for example, lies a fertile, stream slashed valley isolated from the world by almost impenetrable swamps and jungle covered mountains. The Baliem Valley, discovered by explorers in 1938 and visited by the first anthropologists only in 1961, is the home of the Stone Age Dani people. They are skilled gardeners growing a variety of vegetables, yet 90 percent of their diet consists of various preparations of sweet potatoes. Although some 70 varieties are grown, after several days of eating this admirable tuber for breakfast, lunch and dinner, an outsider finds they all begin to taste alike.

While trekking in this beautiful valley in 1976, we passed a hamlet where great activity was taking place. Like all Indonesians, the Dani are extremely hospitable and literally dragged me and my two young children into a compound to join what proved to be a wedding feast. The men, splendid in penis gourds, faces painted with colored clay, and feathers stuck in their woolly black hair, lounged about playing bamboo mouth harps. The women, naked but for a string skirt perched precariously on their hips and almost knee deep in freshly slaughtered pig, busily wrapped chunks of meat in leaves and stacked them onto river stones heated by a fire. Mounds of the inevitable sweet potatoes were laid on top of the pork, followed by a huge pile of leaves. The whole lot was then left to steam just like a Maori hangi which, as a child, I had regarded as unique to New Zealand.

Dani tribesmen from the Baliem valley in Irian Jaya starting a fire to cook the inevitable meal of sweet potatoes.

The food was eventually pronounced cooked and a leaf filled with pork was handed to me by an incredibly filthy woman. As I sat staring at the steaming pork, I thought of all the diseases I might catch. Sheer hunger and desperation for something other than sweet potato finally won out. Unwrapping my little packet of salt (a precious item in the valley, where it could be traded for other goods), I sprinkled some on the pork and took my first mouthful. Moist, sweet, full of flavor I will never forget my Dani pig feast! Even the sweet potatoes tasted good steamed in this earth oven (and I suffered no ill after effects whatsoever).

By contrast, the central Javanese city of Yogyakarta seems to be located on an entirely different planet. Ancient stone temples including the famous Borobudur and the exquisite spires of Hindu Prambanan rise up from the surrounding rice fields, while the classic cone of Mount Merapi periodically showers the land with rich volcanic ash.

The Javanese of Yogyakarta and nearby Surakarta are proud of their refined culture, their dances, gamelan music, batik fabric and intricate handicrafts. Theirs is a highly structured society in which harmony depends upon consideration for others and the group is more important than the individual. Ritual events are marked by a communal feast (selamatan), so it was appropriate that our arrival in the household of a Yogya family, where we were to stay for a year, was the occasion for such a feast.

Prayers were said to confer blessings upon our family and everyone present. The centerpiece of the is a cone shaped mound of yellow rice, symbolic of the holy Hindu Mount Meru. (Although most Javanese are Muslim, earlier animistic, Buddhist and Hindu observances are still incorporated in their rituals.) At least a dozen dishes accompany the rice, including