Jay Rubin - Making Sense of Japanese: What the Textbooks Dont Tell You

Here you can read online Jay Rubin - Making Sense of Japanese: What the Textbooks Dont Tell You full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2021, publisher: Kodansha USA, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Making Sense of Japanese: What the Textbooks Dont Tell You

- Author:

- Publisher:Kodansha USA

- Genre:

- Year:2021

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Making Sense of Japanese: What the Textbooks Dont Tell You: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Making Sense of Japanese: What the Textbooks Dont Tell You" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Jay Rubin: author's other books

Who wrote Making Sense of Japanese: What the Textbooks Dont Tell You? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Making Sense of Japanese: What the Textbooks Dont Tell You — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Making Sense of Japanese: What the Textbooks Dont Tell You" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Previously published in the Power Japanese Series under the titles Gone Fishin (1992) and Making Sense of Japanese (1998).

Published by Kodansha USA Publishing, LLC

451 Park Avenue South

New York, NY 10016

Distributed in the United Kingdom and continental Europe by Kodansha Europe Ltd.

Copyright 1992, 1998, 2012 by Jay Rubin.

All rights reserved.

ISBN9781568364926

Ebook ISBN9781568366081

First edition published in Japan in 1998 by Kodansha international

First trade paperback edition 2002 by Kodansha International

First US edition 2012 by Kodansha USA, an imprint of Kodansha USA Publishing

www.kodanshausa.com

a_prh_5.6.0_c0_r0

This book was called Gone Fishin in its first incarnation, and though it has prompted more enjoyable feedback than anything else Ive ever published, the editors tell me they are tired of responding to readers complaining that the book concentrates too much on Japanese grammar and not enough on trolling for salmon. They have come up with a title that supposedly gives a better idea of the books contents, while my own contribution to this edition is limited to a new section on analyzing difficult sentences. A number of typos have been fixed as well.

I had a great deal of fun writing this bookperhaps too much fun for some tastes, but being neither a grammarian nor a linguist, I felt free to indulge myself in the kind of play with language that I have enjoyed over the past twenty-odd years of reading, translating, writing about, and teaching Japanese literature and the language in which it is written.

My approach may not be orthodox, and it certainly is not scientific, but it derives primarily from the satisfaction inherent in the use of a learned foreign language with a high degree of precision. If nothing else, I hope to share my conviction that Japanese is as precise a medium of expression as any other language, and at best I hope that my explanations of perennial problem points in grammar and usage will help readers to grasp them more clearly as they progress from cognitive absorption to intuitive mastery.

As much as I enjoyed the writing once it got started, I must thank several people for making me put up or shut up. My wife, Rakuko, was the first to urge me to write down some of the interpretations I was teaching my students at the University of Washington, such as the Johnny Carson hodo. Many of the students themselves were helpful: Jody and Anne Chafee, now much more than former students, who will never again translate active Japanese verbs into English passives; John Briggs and Veronica Brakus, among others, who provided new terminology and materials. Sandra Faux of the Japan Society offered a sounding board in her newsletter, and Michael Brase of Kodansha International was the one who made me believe that a bunch of disconnected chapters could be shaped into a book.

I almost hesitate to thank Michio Tsutsui and Chris Brockett, two ordinarily respectable linguists whose reputations could be besmirched by association with this project, but they saved me from some howlers at several points and gave me more confidence in the validity of my analyses than I would have had without their help. Chris, in particular, both cheered and disappointed me when he informed me that others had beaten me to the invention of the central concept of Part One, the zero pronoun. To this day, however, I remain innocent of what he calls a very rich theory of zero pronouns in government and binding theory, a fact of which I should perhaps be ashamed, but my scholarly interests lie in other directions. Linguists may conclude, as he suggests, that I am merely reinventing the wheel or often working in the dark, rather like a nineteenth-century engineer arguing against phlogiston, but students of the language are the ones I am writing for, not linguists, whose technical lexicon keeps most of their no-doubt useful theories effectively hidden from all of us. Talk about phlogiston!

I would strongly urge anyone who has found the book worth reading to send me corrections or suggestions for more and better example sentences or additional topics in need of explication should a revised version become a possibility some time in the future. While the above-named individuals were immeasurably helpful in the development of this book, errors of fact and interpretation are entirely the responsibility of Professor Edwin A. Cranston of Harvard University, to whom complaints should be addressed.

If the format of this series allowed for a dedication page, it would have borne a fulsome tribute to my daughter, Hana, whose good sense, adaptability, intelligence, and patience made me very proud of her during the often trying months in which much of this book was conceived and written.

Learning the Language of the Infinite

Japans economic magnetism has attracted unprecedented crowds of students to Japanese language courses in recent years, but still the number of Westerners who have formally studied Japanese must fall miserably short of the number who have been charmed by the language lesson in James Clavells Shgun. The heroine of the novel, Mariko, introduces the language to the hero, Blackthorne (Anjin-san), as follows:

Japanese is very simple to speak compared with other languages [she tells him]. There are no articles, no the, a, or an. No verb conjugations or infinitivesYukimasu means I go, but equally you, he, she, it, we, they go, or will go, or even could have gone. Even plural and singular nouns are the same. Tsuma means wife, or wives. Very simple.

Well, how do you tell the difference between I go, yukimasu, and they went, yukimasu?

By inflection, Anjin-san, and tone. Listen: yukimasuyukimasu.

But these both sounded exactly the same.

Ah, Anjin-san, thats because youre thinking in your own language. To understand Japanese you have to think Japanese. Dont forget our language is the language of the infinite. Its all so simple, Anjin-san. (New York: Dell, 1975, p. 528)

Of course, Anjin-san has the right idea when he mutters under his breath in response to this, Its all shit. The implication of the scene, however, is that the hero will eventually wise up and immerse himself spiritually in the language of the infinite.

For all the current widespread awareness of Japan, the country remains mysteriously Oriental in American eyes, and the myths surrounding the language are simply one part of the overall picture. Japanese, we are told, is unique. It is not merely another language with a structure that is different from English, but it says things that cannot be translated into Englishor into any other language. Based as it is on pictographic characters, Japanese actually operates in the more intuitive and artistic right lobe of the brain. The Funk and Wagnalls Encyclopedia

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Making Sense of Japanese: What the Textbooks Dont Tell You»

Look at similar books to Making Sense of Japanese: What the Textbooks Dont Tell You. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

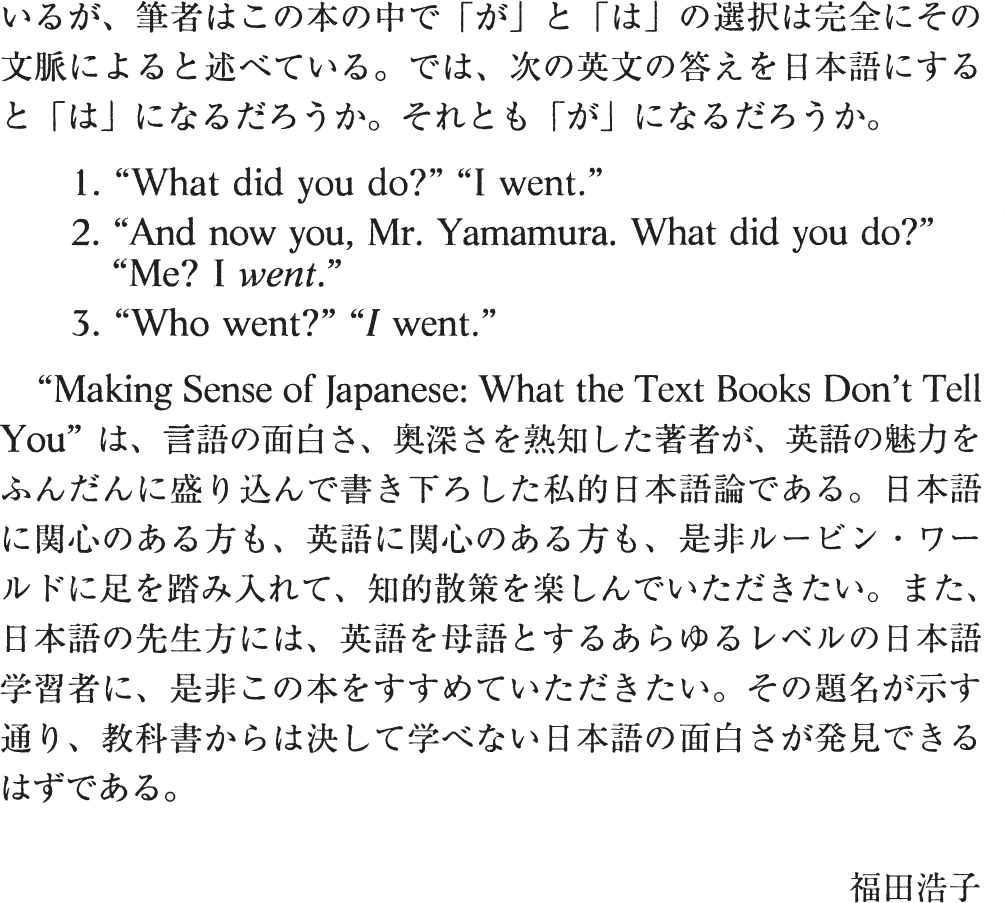

Discussion, reviews of the book Making Sense of Japanese: What the Textbooks Dont Tell You and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.