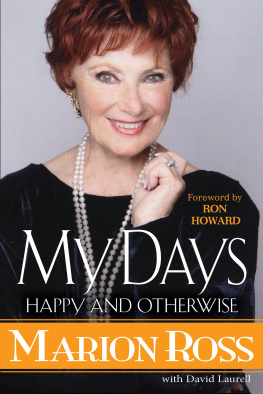

GYRGY FALUDY

My Happy Days in Hell

Translated by Kathleen Szasz

PENGUIN BOOKS

To Suzanne

PENGUIN CLASSICS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL , England

Penguin Group (USA), Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3

(a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephens Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia

(a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0632, New Zealand

(a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL , England

www.penguin.com

First published by Andr Deutsch 1962

Published in Penguin Classics 2010

Copyright Gyrgy Faludy, 1962

All rights reserved

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publishers prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

ISBN: 978-0-14-195960-3

PENGUIN MODERN CLASSICS

My Happy Days in Hell

Gyrgy Faludy was born in Budapest in 1910 and died there in 2006. he was educated at the universities of Vienna, Berlin and Graz and left Hungary in 1938 to live in Paris. He served with the US Army during the Second World War and returned to Hungary in 1946. As dramatized in his famous book My Happy Days in Hell, he was sent to a labour camp on trumped-up charges for three years. After the failure of the 1956 revolution Faludy left Hungary, living first in London and then in Toronto, before returning to Hungary for the final eighteen years of his immensely long life. He was a poet, editor and translator.

PART ONE

France

In November, 1938, in Budapest, I was invited to a party at which the guest of honour was a British MP. There was also a fat, very conservative and melancholy baron at the party, as well as a few skinny, radical and cheerful colleagues of mine from the left-wing periodical financed by the above-mentioned right-wing baron. The principal subject of conversation was Munich and its consequences. We argued, shouted, gesticulated and finally came to the conclusion that Hitler could do in Europe exactly as he pleased. Everyone was excited, only the features of the British Member of Parliament preserved their somewhat waxy, statue-like calm as he explained quietly why Chamberlains policy was correct. When we reached this point, our hostess, a serene and terribly rich lady, no longer young, who made no secret of it that she spent a month or two every year in a lunatic asylum, declared that the topic and mood of our conversation reminded her strongly of the first pages of War and Peace.

Our polite British guest hastily changed the subject and began to question us concerning our plans for the future. Bla Horvath, a young Catholic poet who, regardless of the time of the year and the occasion was wearing a bright, checked jacket, black trousers and a Michaelmas daisy in his buttonhole, declared that he would fight against Hitler even if he had to give his life for Christianity, for social justice and for Hungarys independence. He spoke cheerfully, without tragic pose, and in a low voice so as not to disturb the intimate atmosphere of the silk-lined, box-like little salon. He quoted a great deal from the Fathers of the Church, but even more from Chesterton. At the end of his address he joined his hands as if in prayer, raised large, round eyes to the ceiling and thanked the Holy Virgin and his pet saint, St Catherine of Siena, for blessing him with such virility: a virility proved whenever his sense of duty made him speak at mass meetings, whenever his rebelliousness brought him into court, and whenever his pleasure led him into the bed of a peasant girl.

Horvaths impassioned speech seemed to have further saddened the honourable Member, who said in his reply that he had not come to Budapest to interfere with our affairs, yet now begged us to allow him to express his modest and honest opinion. We were all young, some of us I for instance almost children. He did not wholeheartedly share our radical views, at least not here (by which he probably meant that only Westerners were worthy of freedom; for us even Horthys semi-fascist squirearchy was far too good), but he was afraid that should the Germans march into Hungary we would no longer be in a position to express our beliefs. Our periodicals would be confiscated, our books seized and we would be arrested and hanged in secret. The best advice he could give us, he said, was to leave Hungary. It was not impossible that there would soon be a war in spite of Chamberlains efforts. After the war, however, we could return and serve the ideals for which, today, we would sacrifice ourselves in vain.

We paid no heed to his words because we were too intent upon venting our anger against Chamberlain on the poor man. Two months later all the guests at the party, with the exception of the Catholic poet, had left Hungary. The good baron didnt stop until he reached India. Some had gone to America, others to England.

It was not the honourable Member who made up my mind for me. All he did was to sever the last tie still holding me back my fear that I would be called a coward for running away. Yet I had good reasons to leave. I knew that if I remained I would have to fight in the Hungarian Army as an ally of the Germans. I knew that if Hitler won the war Hungary would disappear from the map and a few decades hence only the Hungarian serfs of the German landowners would still speak Hungarian when, after a long days work, they stretched out their aching bones in the darkness of the stable. Only if Hitler lost the war was there a chance of survival for my country, but even that was not certain. It seemed clear to me that in case of war my place was on the side of the so-called enemy.

I, too, had participated in the tragi-comic dress-rehearsal. I, too, had been called up when the Hungarian Army was mobilized in the days before Munich. We had marched through the streets of Budapest to the railway station, accompanied by a military band. At the back exit of the station, however, we were loaded on lorries and driven back to the barracks. In the afternoon we repeated the performance and in the evening we marched through town for the third time. When, at last, we climbed into the train, we had to take off our new uniforms issued by the government and change into old, ragged ones. At the same time we had to hand in our new repeating rifles in exchange for old carbines into which shells had to be fed one by one.

A few hours later I then commander of one of the signal platoons of the 11th Infantry Regiment lay with my men on the southern shore of the River Ipoly, two hundred yards from the Czechs. To the left I could hear one of the battalions of the regiment wandering purposeless in the under-brush, until they gradually dispersed to lie down in the shelter of hollows or among the maize. They had no guns and most of their officers had remained behind in the villages because they were afraid of an attack. On our right the fields were deserted. The poplars on the shore, high above the Czechs concrete shelters, stood in the moonlight like old actors wrapped in dressing gowns, peering barefoot in the door of the larder to see whether there was any wine left. The thick, russet foliage of the autumnal bushes never stirred, as if it were painted; the stage was set for the great moment of ultimate destruction. While the clatter of the Czech tanks echoed across the water I thought that if they attacked now the Hungarian Army would be routed in two hours and the Czechs would march into Budapest by dawn.

Next page