1

EARLY YEARS

19351957

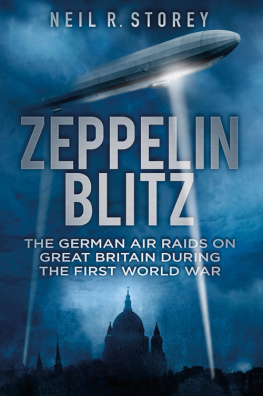

Cecil Beaton,

St Pauls Cathedral, London during the Blitz, 1940

Bill Brandt,

Airraid shelter, London, 1940

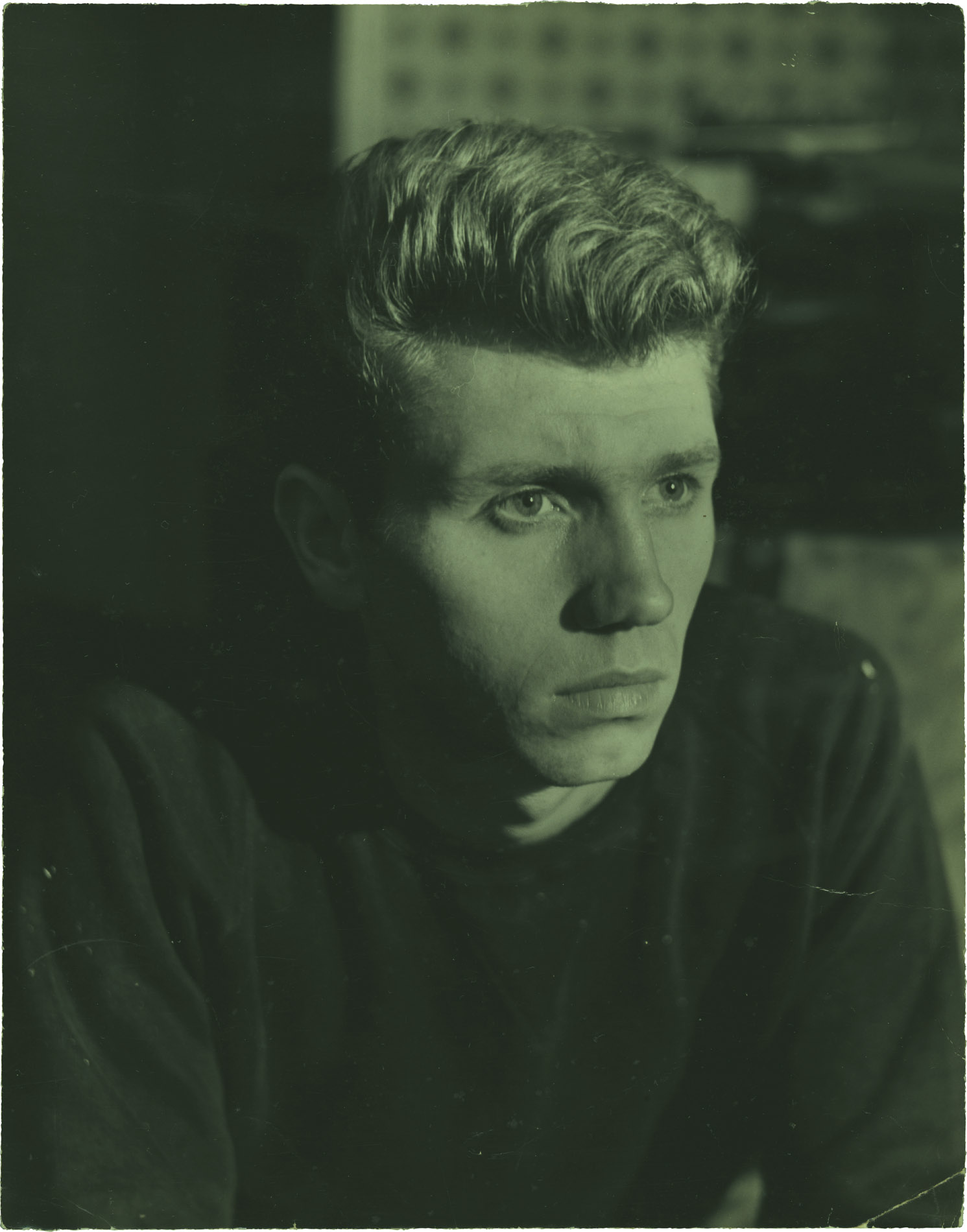

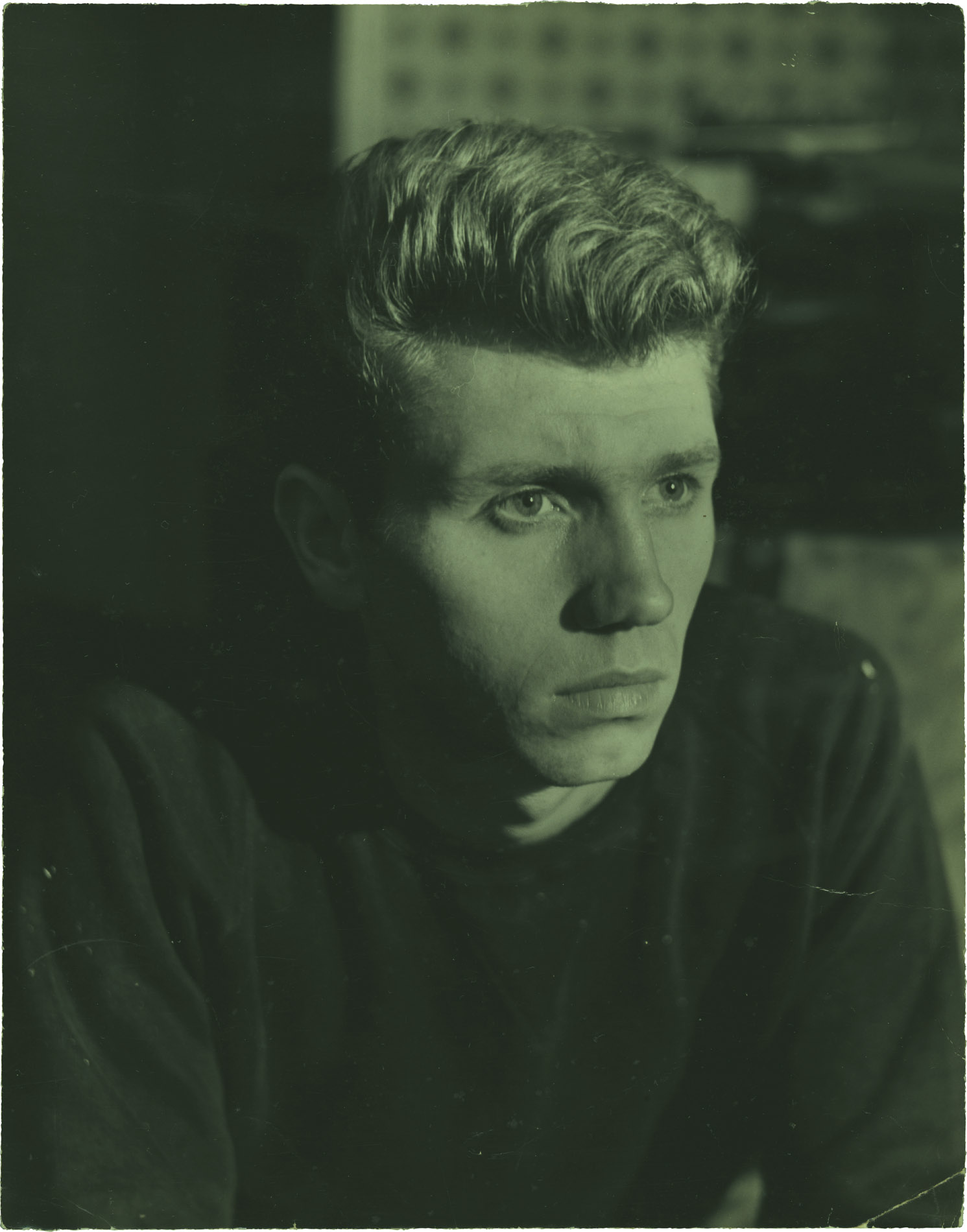

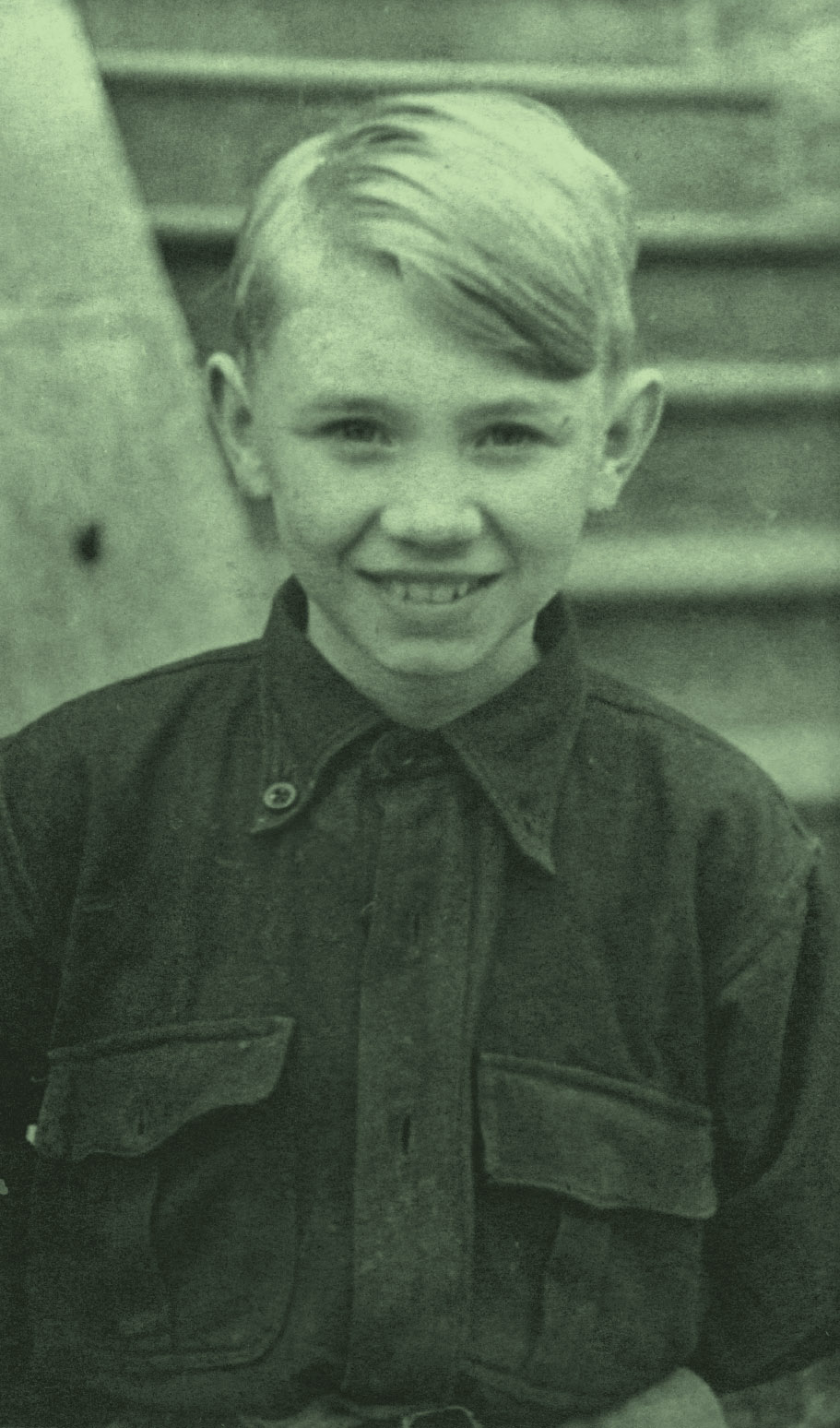

Don McCullin, aged twenty, Finsbury Park, London, 1955

McCullin is an Irish name. My grandmother lived and worked in the Tottenham Court Road area of London and I believe she had a liaison with an Irishman in Camden Town. One of my sons has been scanning the Internet and has even discovered hillbilly McCullins living down in Munro, Louisiana. I came from North London, not far from Camden Town, and then lived in Finsbury Park until I was twenty-five. There were three children in our family myself, my sister, Marie, who was only a year younger than me, and my brother, Michael, who was seven years younger. He fled from England and joined the Foreign Legion when he was about twenty. He walked through the gates of the Legion barracks in Marseilles and stayed there for thirty years. I think he suffered the envy of watching my life unfold as I went to extraordinary and dangerous places. He felt left behind. He used to be an electricians mate, wiring up supermarkets, and there wasnt much of a future in that. He came out of the Legion as an adjutant in their Parachute Regiment. Personally, I feel that thirty years in the Foreign Legion would have been the waste of a lifetime.

When the Second World War was declared, I was plucked out of my primary school and put on a bus with my gas mask. We were sent off very quickly, because bombing was threatened. We were rushed off to somewhere in Huntingdon in Cambridgeshire, but we came back. Then my sister and I were dispatched to Somerset with the express wishes of my mother that we were not to be separated. We arrived in a charming village called Norton St Philip, about twelve miles from where I live now, and everything went wrong. My sister was taken in by a very nice family who were slightly well-to-do and I was sent to a farm labourers council house. She got all the trappings like being served at table by ladies dressed in black-and-white outfits. Sometimes I used to go up to the house, the big house in the village, and look through the window and was chased away. I would be told that my sister was having her tea and it wasnt convenient for me to be there. I grew up with a very defined attitude about those who have and those who have not. It was strange to be looking in at this other world. Bill Brandt, the great photographer, whom I admired so much, took pictures of women dressed in black and white waiting at table or preparing baths in rather grand houses. Life tends to repeat itself visually.

I stayed a year that first time. I remember my father coming to visit and I chased him up the road, crying and pleading for him to take me home. It must have been hard for him. I couldnt do it with one of my own children. He walked away and got on the bus that took him to Frome Station, and back to Paddington, and eventually to horrible Finsbury Park.

I went home for a couple of years, but the bombing was intense and frightening, so my mother shipped me off again. I was sent to Lancashire, which was a totally different experience. I had been in beautiful Somerset, full of leafy glades, slow-moving streams and slightly docile-looking cows munching away on their grass. Suddenly, I was on a train going north to Manchester, a much harsher environment with much tougher people. Ive always found the people in the north of England strong, not just tough, but strong and warm-hearted. In those days there was still the legacy of Victorian Britain. There was that discipline and harshness. I went to a family who had a chicken farm, but unfortunately they turned out to be rather wicked.

When I arrived I was immediately taken to a barber. My head was shaved and I was made to wear clogs. In the Lancashire towns there was the clunking of clogs on cobbled streets. I was out in the country on a farm where the people were terribly unpleasant. I started getting beaten by the man of the house because I wouldnt eat things like boiled potatoes with their skins on. He was very cruel and punched me in the face. We slept on mattresses on the floor. There were no comforts. During the whole seventeen weeks I stayed with that family I never had a bath until the very end. The night before I returned to London, they took one of the dustbins in which they kept the chicken feed. They emptied it and filled it up with hot water.

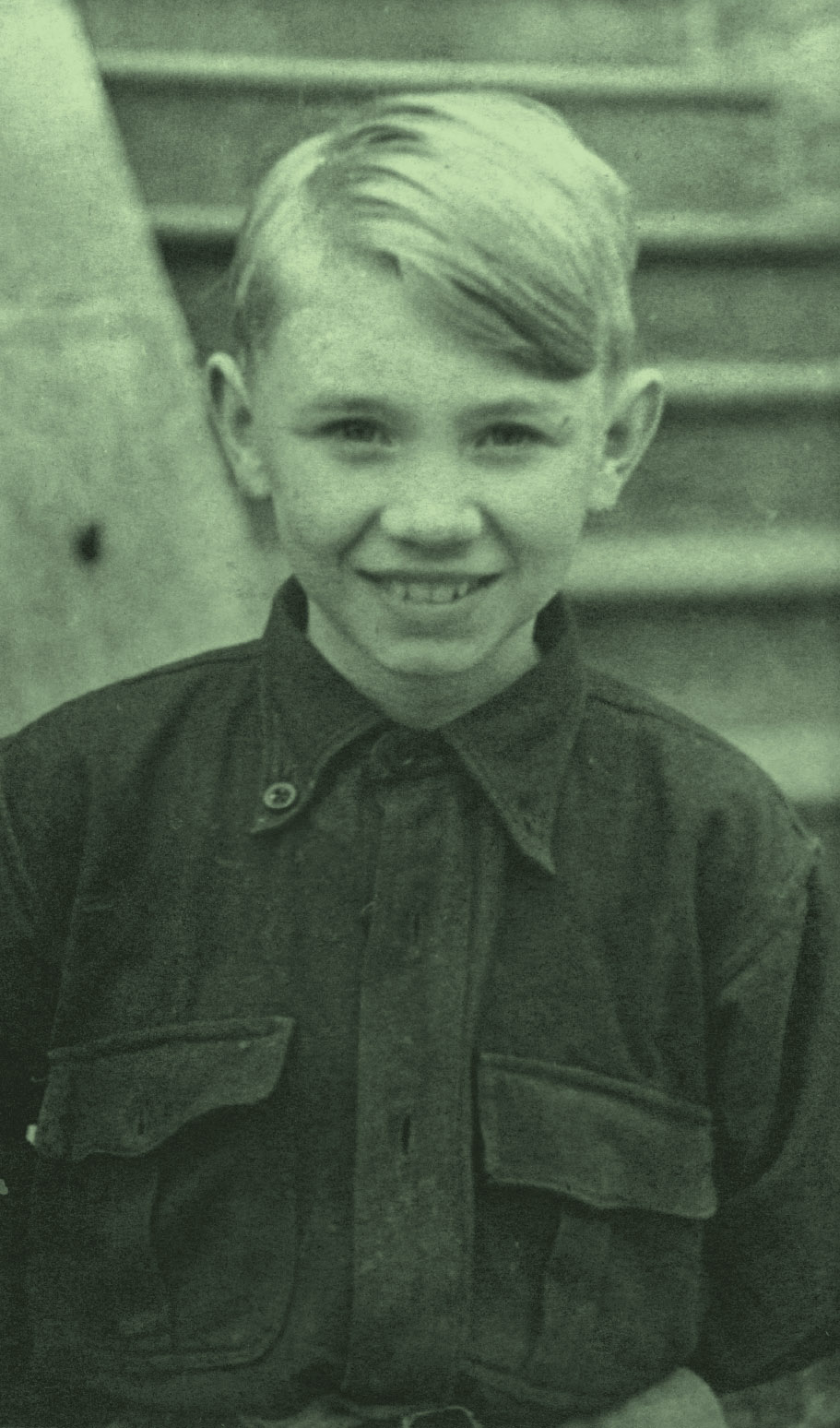

Don McCullin, aged ten, 1945

I look back on it now with some shame for that farmer. But that time helped prepare me to stand on my own two feet. These early experiences can be good or bad for us. Some people can handle them, others cant. I realise now that I certainly grew up then. Im not going to say I was grateful for the experience, for I didnt have much of a childhood that was attractive. I had a fascinating childhood, but it was not the childhood I would offer a child of my own

The war was coming to an end when I got on the train to return to London. It was crowded with soldiers with their greatcoats on those great big itchy greatcoats and there was I coming back with my little bundle of possessions plus a huge bunch of holly for my mother. I must have been a real nuisance on that train because there was hardly room to stand, let alone sit. It was terrible. By some stroke of irony when I was fifteen I was working in the dining car of a London, Midland and Scottish train that went between London and Manchester two or three times a week. Events repeat themselves.

It wouldnt take long to describe my education, because I had very little. Finsbury Park oozed poverty, bigotry and all kinds of hatred and violence. Again, it was preparing me for something I didnt know was coming. Whatever Ive learned, to this day, is what Ive picked up and taught myself. I failed to achieve anything in my younger life. I simply didnt have the ability. I was also slightly disabled with dyslexia, which, back then, those old Victorian schoolmasters wouldnt buy. Lots of thrashings came my way. They thought I was malingering and I really suffered. I think what I am or what I have achieved has been acquired at a purely emotional level. Quite a distinguished writer went away after spending a couple of hours with me at home. In her piece she wrote all kinds of nice things about my work, but she said, He is not a learned man. I was slightly offended by this, because I thought it sounded as if she was putting me down. The truth is I have learned things, and I will always learn for the rest of my life. This has nothing to do with my photography. I believe that we will always be students of life. The moment we think weve cracked it is when weve lost it. I will never believe my photography hasnt still got something to teach me.

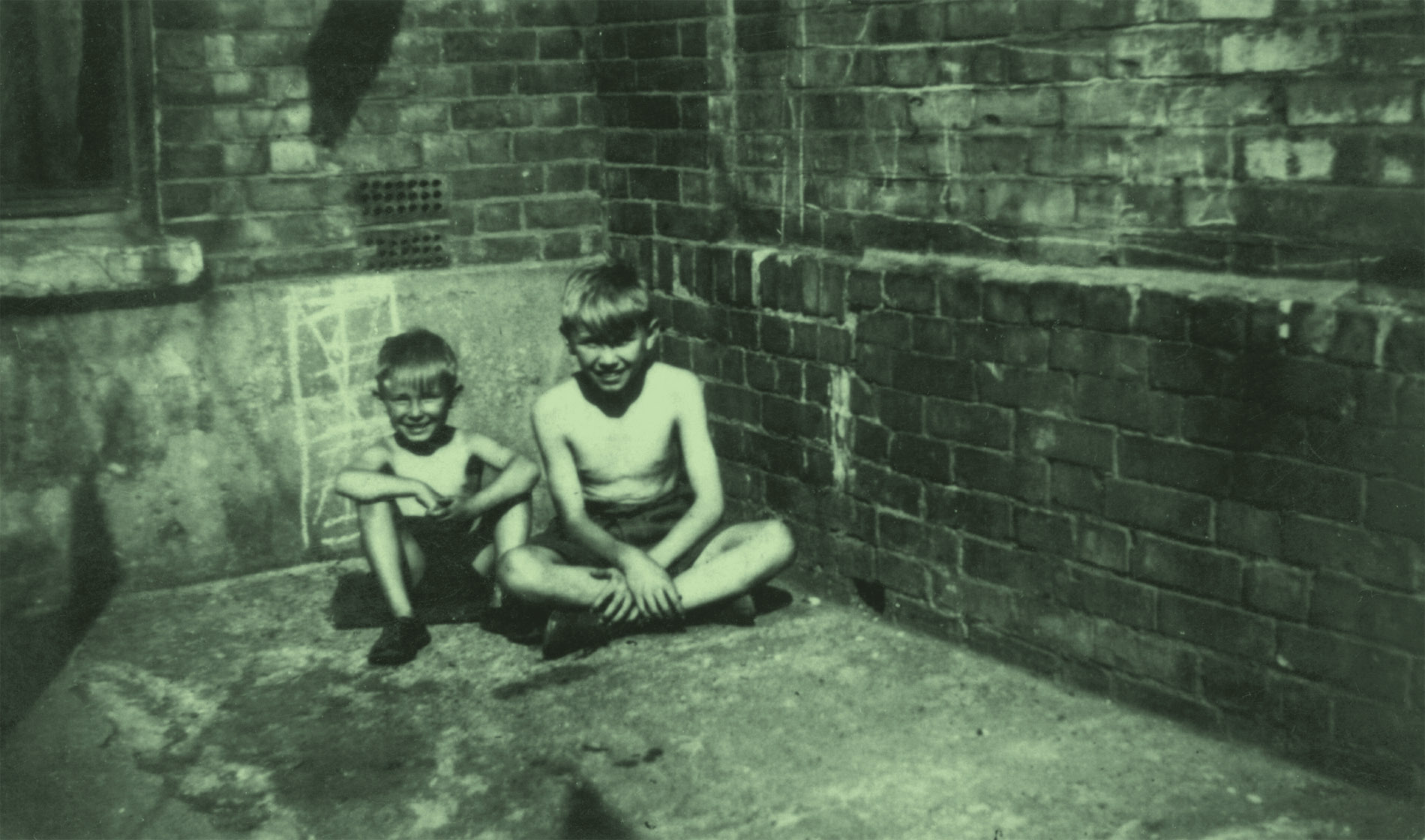

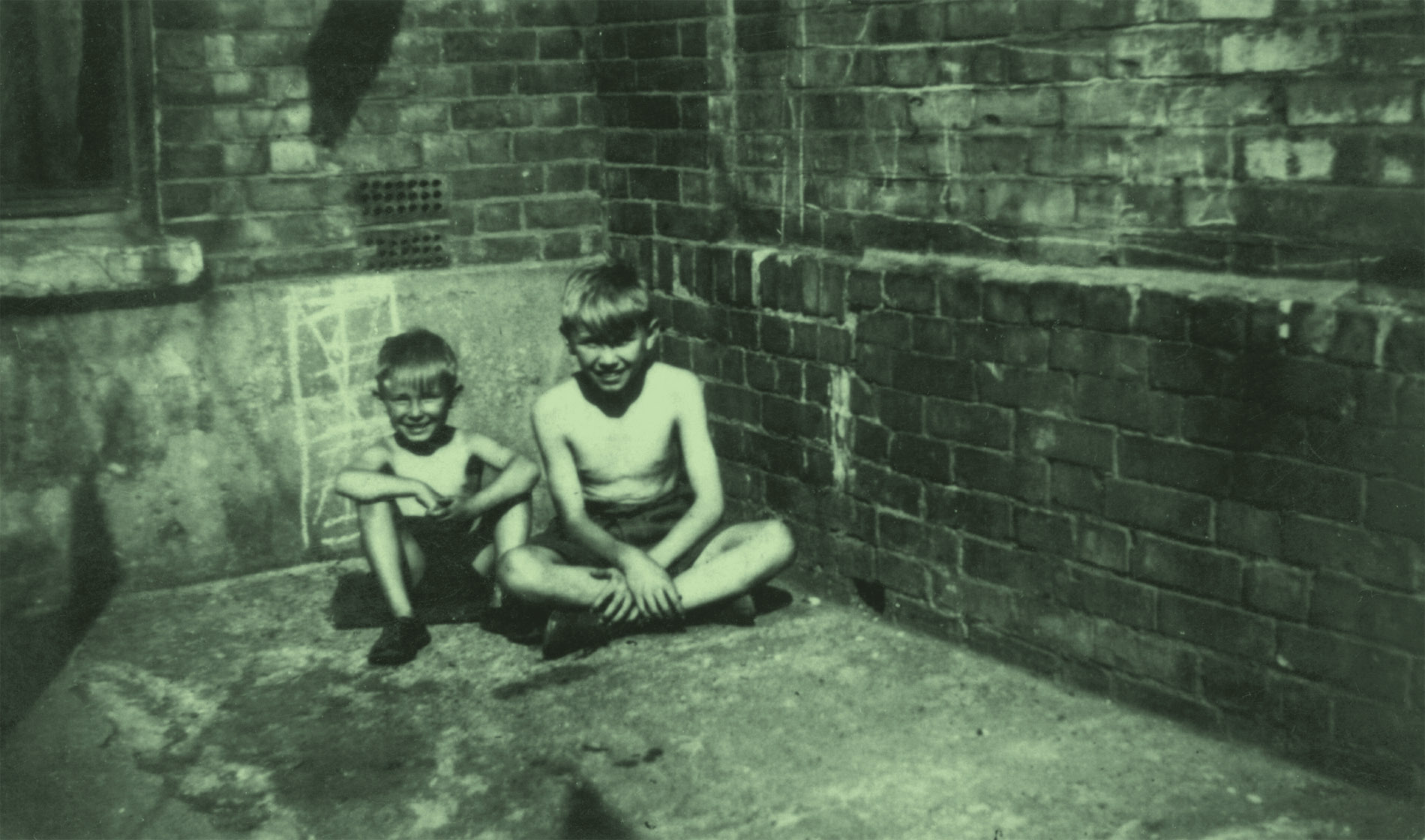

Don McCullin and his younger brother, Michael, Fonthill Road, Finsbury Park, London, 1947

I studied photography by buying a whole stack of books in Cornwall in 1965 when I was working for the Observer. They were called Photograms and the volumes I managed to acquire began in 1886 and ran up to 1926. They cost me ten quid, which was a lot as I didnt earn much. Those books became my photographic university. I still refer to them today. You never stop learning. You never stop discovering. Im constantly being surprised.

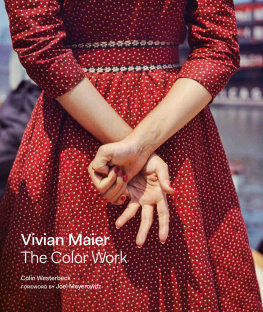

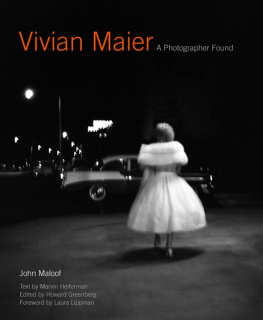

Cecil Beaton,

Cecil Beaton, Bill Brandt,

Bill Brandt, Don McCullin, aged twenty, Finsbury Park, London, 1955

Don McCullin, aged twenty, Finsbury Park, London, 1955  Don McCullin, aged ten, 1945

Don McCullin, aged ten, 1945  Don McCullin and his younger brother, Michael, Fonthill Road, Finsbury Park, London, 1947

Don McCullin and his younger brother, Michael, Fonthill Road, Finsbury Park, London, 1947