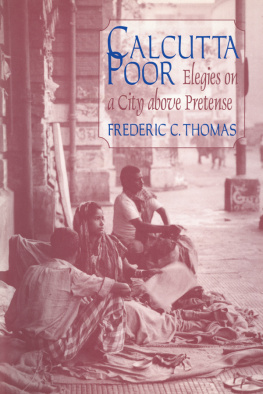

For the destitutes of Calcutta

Jacks parents, Bertha and Harold Preger, who owned a thriving grocery business in Manchester.

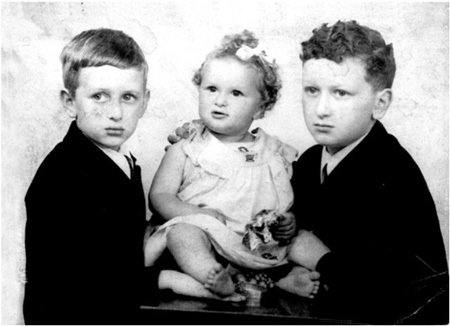

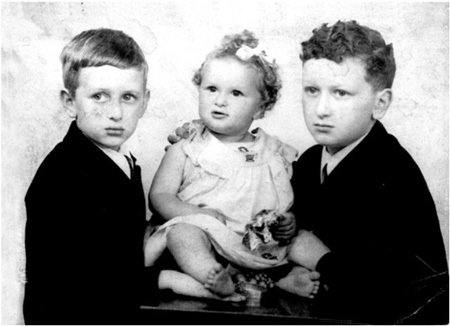

The Pregers three children. Left to right: Leslie, Anita and Jack.

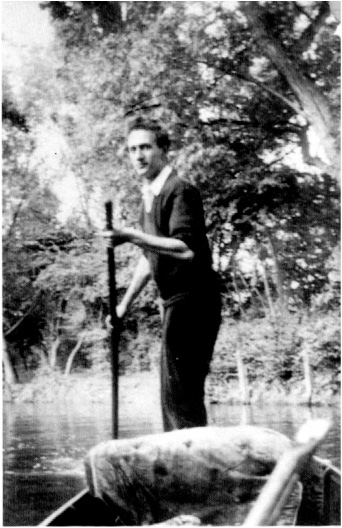

Punting at Oxford. Jack read PPE at St Edmund Hall and was regarded as part of the lunatic fringe.

Gernos Farm, in Wales, where Jack and Marittas son, Alun (visible), was born.

Jack (front row, right) at the Royal College of Surgeons in Dublin, 1971.

Maritta and Alun in London after their separation from Jack.

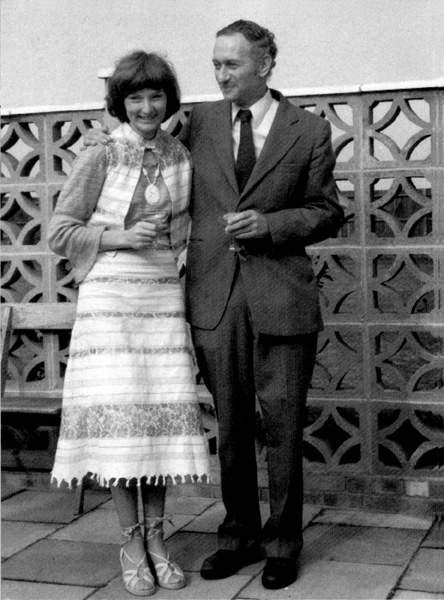

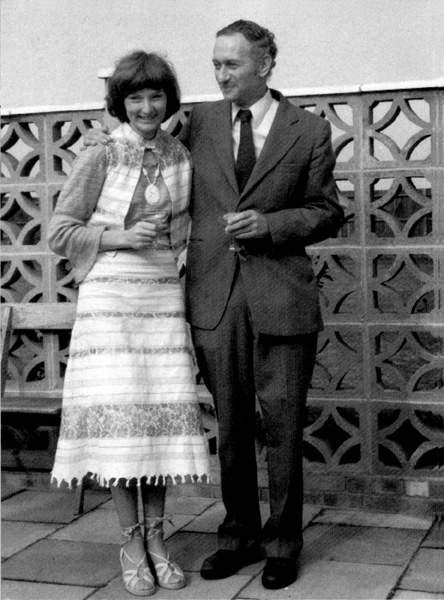

Cathy and Jack on their wedding day in 1977. Jack, accompanied by his new wife, returned to Bangladesh almost immediately after the ceremony.

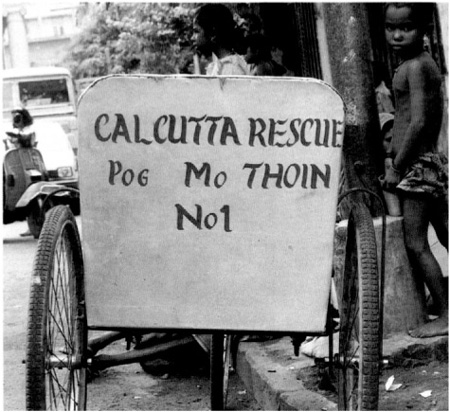

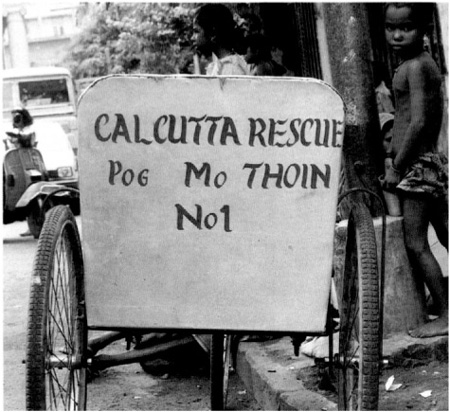

One of Calcuttas familiar invalid tricycles. This one was inscribed with the Gaelic Pog Mo Thoin by Satty, the Irish volunteer who donated it to the clinic.

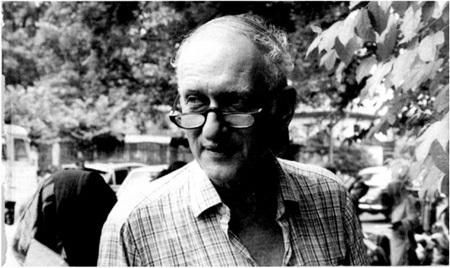

Dr Jack Preger.

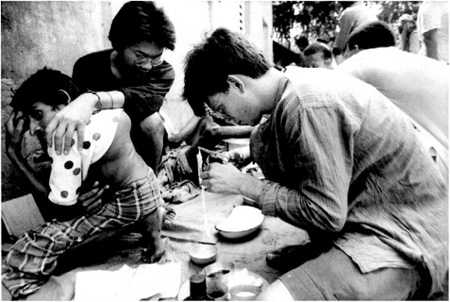

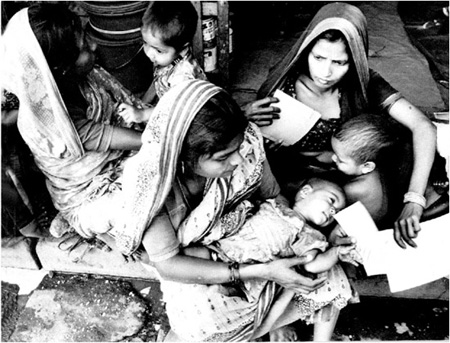

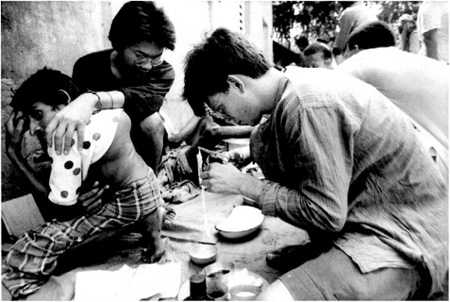

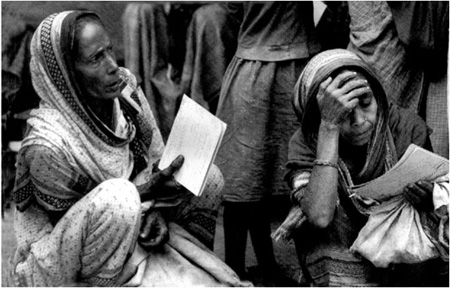

At the street clinic in Middleton Row up to 400 Patients are seen each day

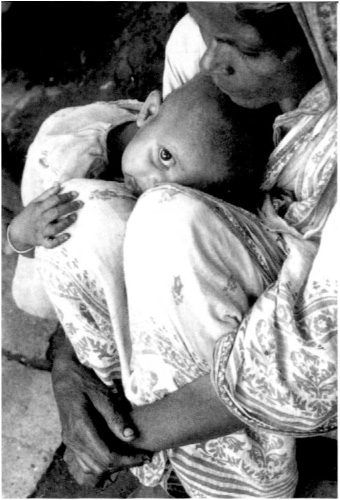

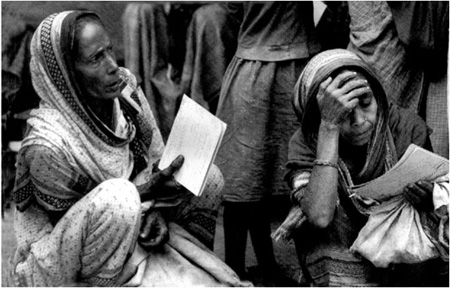

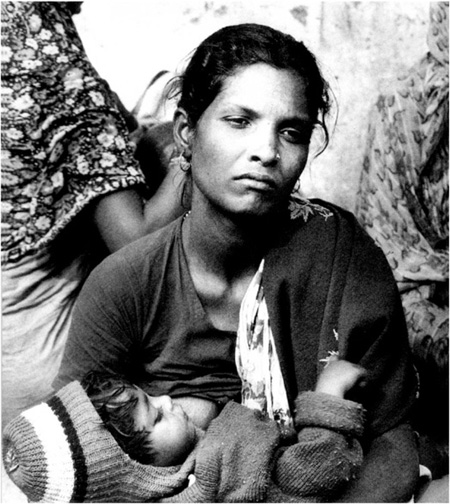

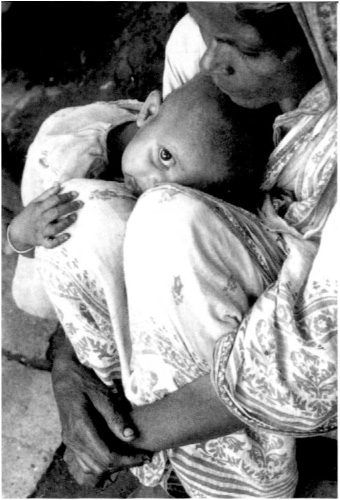

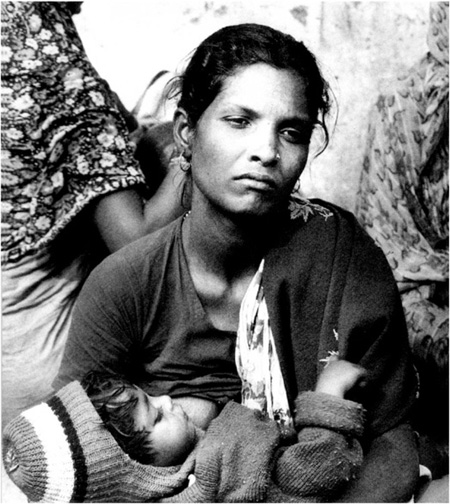

Calcuttas destitutes flock to the narrow strip of pavement where Dr Jack holds his clinic; examinations are free.

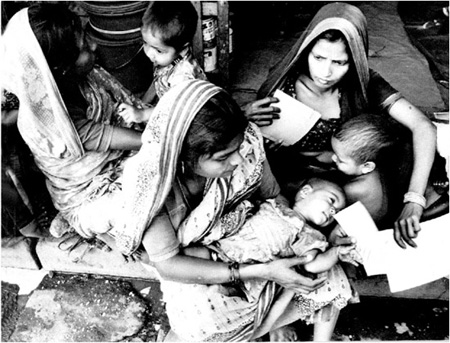

Mothers queue for hours to ensure that their babies are given essential vaccinations.

Contents

The idea for this book began life rather inauspiciously in a black plastic dustbin liner. What happened was that my wife began to talk about an article she had read in the Sunday Times, but only once the papers had been disposed of. She told me the story of the STREET DOCTOR IN CALCUTTA WHO FACES JAIL. Anxious to find a subject for my next book, I retrieved the piece and immediately knew that Jack Preger was it. I think I was attracted towards his story because of my long-standing interest in the twin issues of Jewishness and human rights, which for me have always been inextricably bound up with the Holocaust. And the life story of Jack Preger, once an orthodox Jew and now, perhaps, a Messianic Jew again is all about the quest for human rights. However, any common ground between us ends here. For whereas Jack has been working with the destitutes of Bengal for almost twenty years now, I saw my role, more modestly, as putting on record the achievements of this most remarkable man.

Before leaving for Calcutta in the autumn of 1989, I conducted extensive interviews with Jacks former wives, family and friends. In fact by the time I boarded the Air India jumbo I was convinced that I knew more about him than he knew about himself. What I had found out, though, before meeting Saint Jack, as many a journalist has referred to him, was that he was not quite the saint he was purported to be. Things were a good deal more confused, for I discovered a casualty list of women and children who had been left behind as Jack blazed his amazing trail out East. So it was with some trepidation that I travelled to Calcuttas Middleton Row, unsure if Jack would cooperate with me at all. But when I arrived at the clinic, and Jack greeted me with the immortal words: Ive been a bastard write what you like, I knew immediately that I was unlikely to encounter any such difficulties. And what a sense of humour. I loved Jacks suggestion for the title of this book, revealed in subsequent correspondence between us: The Story of a Nutter in Calcutta. In my view there is no greater gift than being able to laugh at yourself.

Keeping up with Jack was no easy task. In fact, the day before I submitted my manuscript, a ten-page letter arrived informing me that one clinic was opening and another was closing, and that while registration was a little nearer, funding for the clinic was as problematic as ever. Im just wondering whether or not this was what I refer to later as another Preger prank. And I dare say that, come publication day, things are likely to have moved on again. Its the age-old problem of a moving target.

I have changed the names of a few people featured in this book. Once, because I was asked to do so; and on a couple of other occasions because I thought it appropriate. Other than that, everything I have written is true, although needless to say any mistakes are of my own making.

A proportion of the proceeds of this book will go to the Calcutta Rescue Fund, the Preger support group that is active in the UK and sent over 100,000 to Calcutta in 1989. A full list of contact names and addresses is given on 6.

There are so many people to thank for their help that I shall just list their names rather than specify the precise manner in which each assisted me. Its a little like putting a jigsaw together: had any of the following names been missing, the picture would have been incomplete. So I would like to express my appreciation to Jonathan D. Rose, Diane Booth, Frances Meigh, Chaim Neslen, John Justice, Helene Rogers and Bob Turner, the Basu family in Calcutta, Suzanne Franks, Kevin Mulley, Anita Ostrin, Leslie Preger, Shaemus Cunnane, Cathy and John McGregor, Antonia Walder, Maritta Preger, Allen Jewhurst, Ben Kingsley and all members of the Josephs and Frank families.

Whether or not I should thank my wife Clair for encouraging me to retrieve that article from the bin, I really dont know. Because by so doing she was in effect giving me an enormous amount of work, which took almost two years to complete. But if I have suffered, she did too, as I inflicted one rewrite after another on her.

Next page