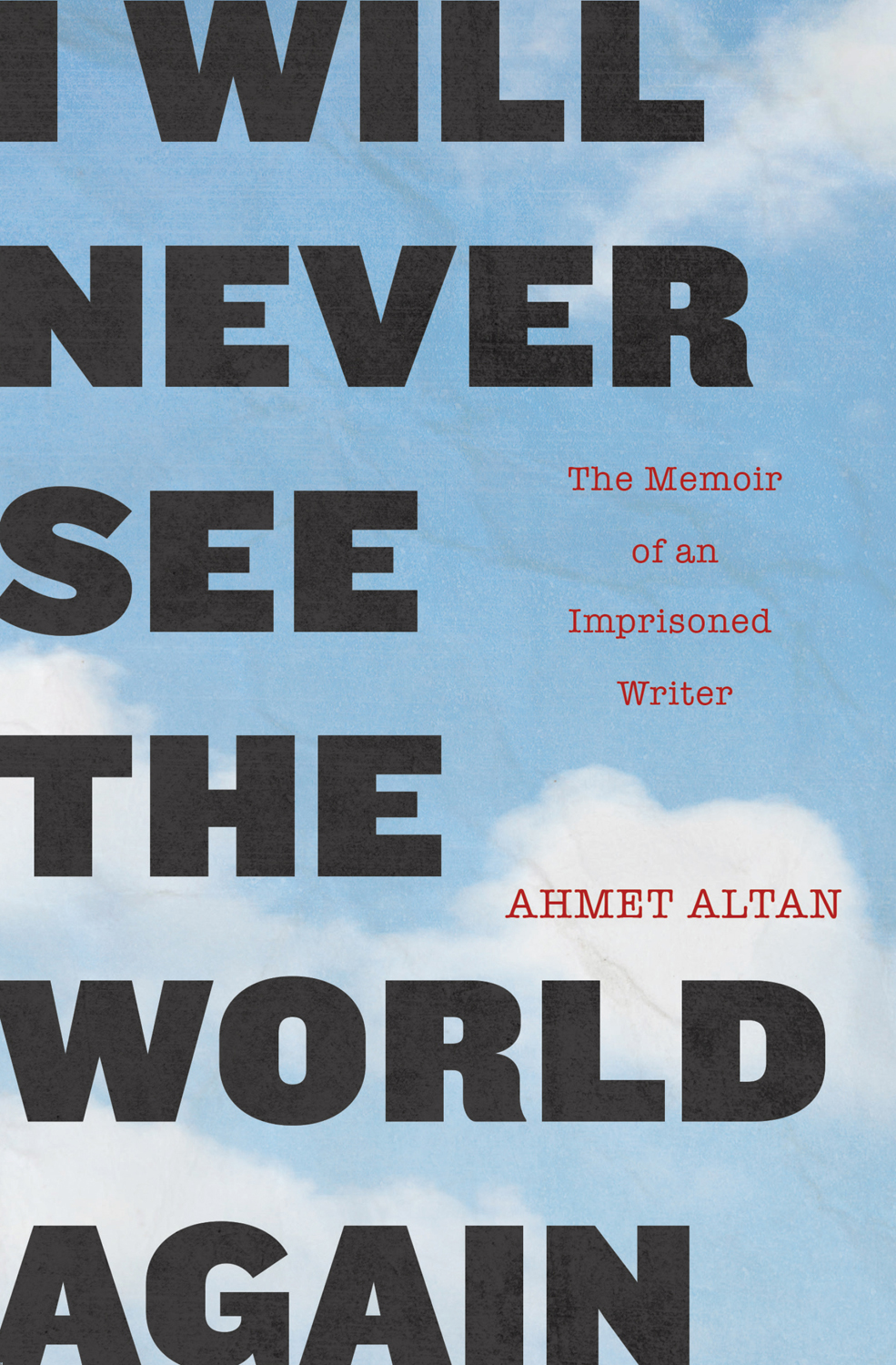

Ahmet Altan - The Memoir of an Imprisoned Writer

Here you can read online Ahmet Altan - The Memoir of an Imprisoned Writer full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2019, publisher: Other Press, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Memoir of an Imprisoned Writer

- Author:

- Publisher:Other Press

- Genre:

- Year:2019

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Memoir of an Imprisoned Writer: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Memoir of an Imprisoned Writer" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Memoir of an Imprisoned Writer — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Memoir of an Imprisoned Writer" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Also by Ahmet Altan

Endgame

Like a Sword Wound

First published in Great Britain by Granta Books, 2019

Copyright Ahmet Altan, 2019

Translation copyright Yasemin ongar, 2019

Foreword copyright Philippe Sands, 2019

The following essays have previously been published in slightly different forms: The Novelist Who Wrote His Own Destiny as I Will Never See This World Again in the New York Times on February 28, 2018; The Writers Paradox in the winter 2017 issue of the Author, the journal of the Society of Authors in the UK.

The moral right of the author and translator has been asserted.

Production editor: Yvonne E. Crdenas

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from Other Press LLC, except in the case of brief quotations in reviews for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast. For information write to Other Press LLC, 267 Fifth Avenue, 6th Floor, New York, NY 10016. Or visit our Web site: www.otherpress.com

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Names: Altan, Ahmet, author. | ongar, Yasemin, 1966- translator. | Sands, Philippe, 1960- writer of foreword.

Title: I will never see the world again : the memoir of an imprisoned writer / Ahmet Altan ; translated from the Turkish by Yasemin ongar ; foreword Philippe Sands.

Description: New York : Other Press, 2019. | First published in Great Britain by Granta Books, 2019.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019017340 | ISBN 9781590519929 (paperback) | ISBN 9781635420005 (Ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Altan, AhmetTrials, litigation, etc. | JournalismTurkey | Political crimes and offensesTurkey. | TurkeyPolitics and government1980-Classification: LCC PL248.A525 A6 2019 | DDC 894/.358303 [B]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019017340

Ebook ISBN9781635420005

v5.4

a

I first met Ahmet Altan in the spring of 2014, at a gathering in Istanbul. The city has long been special to me, as the place where I fell in love thirty years ago, drinking mint tea at a small cafe by the Ortaky Mosque in the shadow of the Bosphorus Bridge, with the woman I would marry. That spring, Ahmet delivered the first Mehmet Ali Birand Lecture, a now annual event organized by press freedom group P24 to honor the memory of a renowned Turkish journalist. I appreciated Ahmets lecture, and immediately liked him. He spoke with passion and courage, intelligence and humor on the writers place in a decent society. Soon we became friends and were often in touch, seeing each other in London and Istanbul.

Four years after Ahmet and I met, in the spring of 2018, I was invited to give the same annual lecture in the same building: the splendid nineteenth-century pile that is the Swedish Consulate General in Beyolu on the European side of Istanbul. Ahmet was invited but not able to attend; by then he had been in prison for 590 days. His crime? To speak a few innocuous words on a television program in the aftermath of the failed 2016 coup, which were interpreted as treasonous by President Recep Tayyip Erdoans government.

President Erdoans crackdown had left Turkey languishing near the bottom of the Reporters Without Borders World Press Freedom Index. The situation was bad and likely to get worse, even if there was a sense that President Erdoans position was not entirely secure in forthcoming elections. The economy was suffering; tourists were staying away. The atmosphere at the Swedish consulate on that spring night in 2018 was one of grim resolve.

My lecture was attended by writers and journalists yet to be arrested. Murat Sabuncu, the editor-in-chief of the Cumhuriyet newspaper who had been sentenced in April 2018 to seven-and-a-half years on terror charges but released on bail pending appeal, introduced the proceedings. His speech was an impassioned salute to the many journalists who had been arrested.

I dedicated my lecture to Ahmet. We know how words are apt to be interpreted in different ways, I said, explaining a point of connection between lawyer and writer, and we know too that that is their beauty and their danger. The dangerous words spoken by my dear, absent friend caused a judge to rule that Ahmet, who was sixty-eight at the time, would spend the rest of his life in prison. We will never be pardoned and we will die in a prison cell, Ahmet wrote in the New York Times, after being sentenced, from his prison cell.

The following day was spent with Yasemin ongar, who runs P24 and is Ahmets close friend. We traveled together to the maximum-security prison at Silivri, a two-hour drive from Istanbul. This was where Ahmet was incarcerated, along with his younger brother Mehmet, an economist fired from his position at Istanbul University, where he had taught for thirty years. Yasemin has not been allowed to visit Ahmet she is permitted ten minutes on the telephone every fortnight and nor had any foreigner. I was the first allowed in to see Ahmet, because I was acting as a lawyer for the Altan brothers at the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg.

The facility was huge and forbidding, holding 11,000 prisoners. Accompanied by a Turkish lawyer, I passed through at least eight security checks and was taken by minibus to Block 9. I was not subjected to the full body search, but was required to have my eyes scanned, to be integrated into the system. One of the guards was friendly and wanted to talk soccer. We had a short, happy conversation about Arsene Wenger, Mesut zil (who, much to my sadness, would soon be photographed handing over an Arsenal shirt to President Erdoan), and what it meant to be Turkish. He had worked there for four years and never encountered a foreigner. You are the first, he said with a smile.

I met first with Mehmet, who was genial and gentle and had twinkly eyes and a full Karl Marx beard. He was thrilled to talk in French, surprising me with ideas about globalization and the English Luddite movement, on which he had ample time to write. He shared a cell with two other men, one of whom was a former student. Mehmet was perplexed by his situation, and the prospect of spending the rest of his life in prison. A life sentence, he said, is like living without clocks, in endless time. (Three months later, in the summer of 2018, Mehmet was released.)

Mehmet left. I waited, then Ahmet arrived in our glass-paneled cell. He looked fit. Weights! he chortled. We spent most of our thirty minutes roaring with laughter. No, he said, Turkey had not hit rock bottom yet. We are a nation of bungee jumpers, and just before we hit the ground we somehow manage to bounce up again. We talked about food, politics, the quality of the grass in my garden in London, and my neighbor, the English magistrate who signed the arrest warrant for Senator Pinochet back in the autumn of 1998. Ahmet marveled again at the idea of justice being dispensed by a judge who was independent. A miracle, he said.

What did he want his readers to know? I asked. We talked of the judge who sentenced him, a man of swollen eyelids. Ahmet knew I had a special interest in judges, especially those of the less independent kind. Later I would learn that the name of the man who sentenced Ahmet to life imprisonment for no good reason was Judge Kemal Seluk Yalin.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

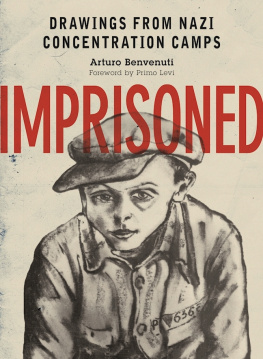

Similar books «The Memoir of an Imprisoned Writer»

Look at similar books to The Memoir of an Imprisoned Writer. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Memoir of an Imprisoned Writer and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.